Sex, booze and 18th-century Britain

If you ever needed proof that the sex, booze and a rock’n’roll lifestyle was not a twentieth century invention, you need look no further than the satirical prints of William Hogarth. He held up a moralizing mirror to eighteenth-century Britain; the harlots, the womanizers—even the clergy could not escape. Hogarth’s prints play out the sins of eighteenth-century London in a kind of visual theater that was entirely new and novel in their day.

William Hogarth, A Harlot’s Progress, plate 1, 1732, etching with engraving on paper, 31.4 x 38 cm

The first example of these prints, which Hogarth himself termed ‘modern moral subjects’, was A Harlot’s Progress. In this series, we meet the fresh faced Moll Hackabout as she arrives for the first time in London. Moll is soon preyed upon by a brothel keeper and she descends into prostitution. The tale ends with her premature death from a sexually transmitted disease, aged just twenty-three. Despite its dark subject matter A Harlot’s Progress was a huge success. These prints reference characters types who were well known to their contemporary London audience. For example Moll’s madam was the real-life Elizabeth Needham, keeper of an exclusive London brothel and her first patron, the renowned love-rat and convicted rapist, Colonel Francis Charteris.

A Rake’s Progress

These sly nods to the bad guys of the day not only made the prints hugely relevant and enjoyable to their target audience but it also made them incredibly popular. A Rake’s Progress (1735) was Hogarth’s second series and proved to be just as well loved. The main character is Tom Rakewell—a rake being a old fashioned term for a man of loose morals or a womanizer. Tom’s name is intentionally general and in a modern equivalent, he might be called ‘Mr. Immoral.’ Tom is not unique, he could be any number of people in eighteenth-century Britain.

The series opens with a chaotic scene: Tom’s father, who was a rich merchant, has died and Tom has returned from Oxford University to collect and spend his late father’s wealth. He also wastes no time in rejecting his pregnant fiance, Sarah Young, by attempting to pay her off. Hogarth laces all his prints with clues to help us decode the scene. Here we can see Sarah sobbing into a hankie whilst holding her engagement ring in her hand. Her mother stands behind her angrily clutching the love letters Tom once wrote to her daughter and he holds out a handful of coins in an attempt to get rid of them. Sarah pops up throughout these prints representing a more wholesome life that he could have had.

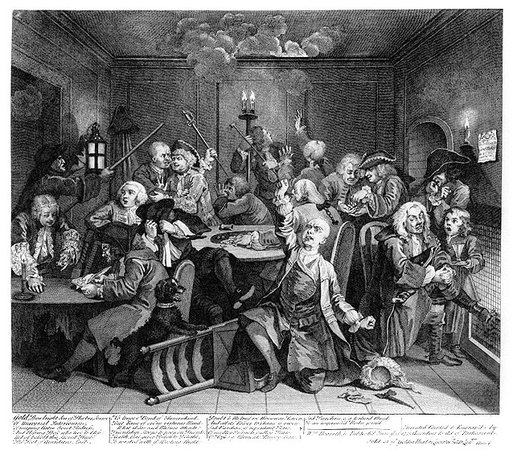

William Hogarth, A Rake’s Progress, plate 2, “Surrounded by Artists and Professors,” 1735, engraving on paper, 35.5 x 31 cm

A fashionable life

By the next scene (“Surrounded by Artists and Professors,” above) Tom has already moved from his cozy, if slightly shabby family home into his new bachelor pad surrounded by a dance master, a music teacher, a poet, a tailor, a landscape gardener, a body guard and a jockey all offering their services to help Tom complete his fashionable lifestyle. He is dressed in his nightclothes indicating that he has just woken: those who wish to exploit his new found wealth are wasting no time.

Tom’s fashionable life also comes with fashionable vices and soon we see him in the Rose Tavern with a group of prostitutes (see “The Tavern Scene,” below). He sits on the lap of one who caresses him with one hand whilst robbing him of his watch with the other. Portraits of Roman Emperors hang on the wall behind them but the only one that has not been defaced is Nero’s. This is perhaps hard for a modern audience to identify but there would have been a significant number of Hogarth’s classically educated audience who got the gag: Nero was a corrupt womanizer who fiercely persecuted Christians. To the very classically aware Georgians (George II was then King) the message was clear, Christian morals are not to be found here.

William Hogarth, A Rake’s Progress, plate 3, “The Tavern Scene,” 1735, engraving on paper, 35.5 x 31 cm

A decadent decline

Tom’s decadent lifestyle does not last for long and by the third scene his sedan chair is intercepted by bailiffs as he is en route to the Queen’s birthday party. It is at this point that our heroine Sarah Young comes to the rescue. She is now working as a milliner and kindly pays Tom’s bail. Although Sarah has saved Tom from the bailiffs, she cannot save him from himself. By the next scene he is marrying a wealthy old hag. The old woman’s eyes lust eagerly towards the ring and Tom’s towards her maid. In the background Sarah Young and her mother struggle to voice their objections but are held back by some of the guests.

Tom is wealthy again but he is no better with his money now than he was last time and soon he is on his knees in a gambling den having just squandered the lot (see “The Gaming House,” below). Excessive gambling was a real problem in the eighteenth century and whole family fortunes could be lost in one evening. Later in the century, George III’s son, who later became George IV, had to ask Parliament for money to help him pay off his gambling debts. It was given to him but it was not long before he needed even more.

William Hogarth, A Rake’s Progress, plate 6, “The Gaming House,” 1735, engraving on paper, 35.5 x 31 cm

Debtors’ prison

Like so many others in eighteenth-century Britain, Tom finds himself in debtors’ prison, quickly coming to the end of his tether. On the one side his wife derides him for squandering their fortune, on the other the beer-boy and the jailer harass him to settle his weekly bill. Sarah Young, who has come to visit Tom with their child, has fainted on seeing him in this hopeless situation. This must have been very personally relevant for Hogarth as his father spent much of his childhood in a debtors’ prison.

My favorite part of the series is played out in the background of this scene. Tom’s fellow inmates are trying various schemes to get enough money to buy their freedom. However, their choice of projects cleverly illustrate just how impossible it was to get out of debt in Georgian Britain. One man is attempting to turn lead into gold while the other is working on solving the national debt crisis. Even Tom has written a play, though we can clearly see a rejection letter for it lying on the table.

William Hogarth, A Rake’s Progress, plate 8, “The Madhouse,” 1735, engraving on paper, 35.5 x 31 cm

Bedlam

The stresses of the previous scene have proven to be more than Tom can bear and in the final scene he is found languishing in bedlam—London’s notorious mental hospital (see “The Madhouse,” above). The mark on his chest suggests that he has stabbed himself in a failed suicide attempt. Fashionable young women, the likes of which Tom would have socialized with just a short while ago, observe the scene in amusement. All that he has left is the company and care of the faithful Sarah Young.

Why so popular?

One answer is that it appealed to the contemporary concern about people from the middle classes who tried to live like aristocrats. This was a popular issue at this time as the merchant trade was creating social mobility on a scale never seen before. However if we scratch the surface of A Rake’s Progress we can see that a number of different types of people implicated. For example, Tom was on his way to the Queen’s birthday party when he was stopped by bailiffs and therefore his lifestyle is actually being encouraged and supported by aristocrats. In A Rake’s Progress, everyone from the Queen to the priest that performs his marriage of convenience, to common prostitutes, are part of the problem.

But it is not just Hogarth’s ‘take no prisoners’ approach to social commentary that made him so popular. Printed satire was actually already very common place and central London was full of bookshops and print sellers that displayed this kind of work. What Hogarth did do that was so completely novel was to tell a story through pictures, A Rake’s Progress is like a story board for a play. In fact, Hogarth’s series were adapted into plays and pantomimes during his lifetime. His visual drama offered his audience a new way to enjoy satire. It is for this reason that to find comparisons and inspirations we should be looking at authors such as Hogarth’s friend and fellow moralizer, Henry Fielding or Jonathan Swift—author of Gulliver’s Travels, rather than contemporary artists. The title A Rake’s Progress was referencing John Bunyan’s The Pilgrims Progress. We can be quite sure that most people would have gotten this reference as it is thought that, at this time, this was the most read book in Britain after the Bible. Hogarth successfully borrows from popular culture in order to express complicated ideas through an enjoyable and totally accessible story. Of course Hogarth wasn’t the first to do this, but he did it so well, he is celebrated to this day.

Additional resources:

The original painted series from 1733 at Sir John Soane’s Museum