Jan Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, tempera and oil on oak panel, 82.2 x 60 cm (National Gallery, London), photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

But is she pregnant?

Jan van Eyck’s equally enigmatic and iconic Arnolfini Portrait often prompts art history newcomers and experts alike to ask: is the female figure pregnant? Questions about the presence of pregnancy in the portrait are so common that the London National Gallery’s website addresses the issue on the second line of the painting’s official explanatory text.

Jan Van Eyck, Dress (detail), The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, tempera and oil on oak panel, 82.2 x 60 cm (National Gallery, London), photo: Dr. Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Is the woman in the Arnolfini Portrait pregnant? The short answer is no. The illusion is caused because the figure collects her extensive skirts and presses the excess fabric to her abdomen where it springs outwards and creates a domelike silhouette. Her hand position is regularly read by modern viewers as a universal acknowledgment of pregnancy, but in the Renaissance this gesture would have been understood instead as a sign of adherence to female decorum. Young Renaissance women were encouraged to keep their hands demurely clasped around their girdles when in public, as this was seen as polite and unobtrusive.

The issue of pregnancy in the Arnolfini Portrait is a complex one: the figure is not literally pregnant, because painting or sculpting pregnancy violated the period’s artistic customs—yet pregnancy is nevertheless present in the picture. Both pregnancy symbolism and expectation are at play within the painting.

Jan Van Eyck, Oranges (detail left) and carved bedpost depicting Saint Margaret atop a dragon (circled in red, detail right), The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, tempera and oil on oak panel, 82.2 x 60 cm (National Gallery, London), photos: Dr. Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Objects alluding to future pregnancy pepper the composition, from the ripened fruit arranged on the windowsill, to the wooden statuette of Saint Margaret, the patron saint of childbirth, who is shown overcoming the dragon of heresy on the bed frame. Though it’s impossible to sever the question concerning pregnancy from this painting, we can answer it by examining both Renaissance pregnancy and dress practices.

Renaissance pregnancy

The highly-gendered Renaissance world produced widely disparate male and female lived experiences. While a man generally married in his third or fourth decade, allowing him ample time to grow his business or estate, women became brides ideally between the ages of thirteen and seventeen. Women, therefore, were expected to and did spend the majority of their married lives with child.

Jan Van Eyck, Hands (detail), The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, tempera and oil on oak panel, 82.2 x 60 cm (National Gallery, London), photo: Dr. Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Arnolfini’s wife is not pregnant in the picture, but period norms assumed she soon would be. Art historian Diane Wolfthal agrees that although the woman is not pictured pregnant, “the panel alludes to the proper goal of sexual relations through the wife’s protruding belly . . . her gesture . . . brings attention to her womb,”[1] and argues that the few period viewers who came into contact with the Arnolfini Portrait would have understood and recognized this signaling.

Raphael, La Donna Gravida (Portrait of a Woman), c. 1505–06, oil on panel, 66 x 52 cm (Palazzo Pitti, Florence)

Although married Renaissance women spent the majority of their premenopausal lives with child, pregnancy itself was rarely represented. Artists working across a myriad of media shied away from depicting pregnancy, most likely because the condition was thought to be indecorous.

During the Renaissance, when a woman entered into her third trimester, she generally remained at home in a ritual called confinement. Further, depicting pregnancy admitted a direct link to human sexuality. Though procreative intercourse between heterosexual married couples was the only church-sanctioned form of sexuality in the Renaissance, to portray a married woman pregnant was generally seen as improper.

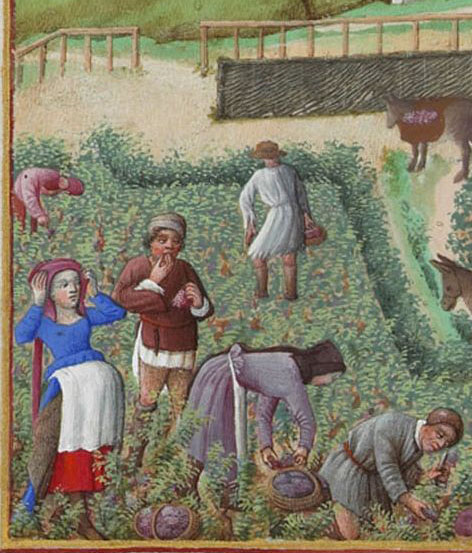

Detail, Limburg Brothers, September from Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, f. 9, c. 1412–16 (Musée Condé)

Rare exceptions exist, such as Raphael’s inscrutable Donna Gravida, or Portrait of an Unknown Lady attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts II, or the peasant woman toiling away in the fields in the September page of the Limbourg brothers’ Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry.

But even paintings depicting the Visitation—a moment in the Gospel of Luke when Mary and Elizabeth meet and both are pregnant (Mary with Christ, and Elizabeth with St. John the Baptist)—the two biblical heroines are rarely depicted as obviously gestational, though again, there are a few exceptions (for example, Rogier van der Weyden’s Visitation).

Francseco Xanto (painter), Cup (for broth) from a birth tray c. 1530, tin glazed earthenware, 16.5 cm diameter (Victoria & Albert Museum)

Another medium that offers a glimpse into Renaissance pregnancy and childbirth are birth trays, which were popular gifts for new mothers that would include jars and bowls containing soup and sweets.

Renaissance dress and gender norms

While the Arnolfini Portrait foregrounds many domestic objects, dress takes center stage. Both outfits in the portrait are ludicrously expensive and detailed, but the woman’s clothing outshines her husband’s. This excessive disparity in color and yardage is perfectly in line with Renaissance fashion and gender difference. Men’s outfits tended to be tailored from darker fabrics to signal the wearer’s sobriety and lack of vanity. In contrast, Renaissance women’s bodies in both images and reality were potent sites of material display. An exemplary upper-class wife was required to demonstrate her husband’s wealth (through his ability to keep her adorned in the latest fashion trends) as well as the couple’s potential fertility.

Unknown artist, A Bridal Couple, c. 1470, oil on panel, 77.5 x 51 x 8.1 cm (The Cleveland Museum of Art)

The woman in the Arnolfini Portrait holds her dress in a way that styles her body as seemingly pregnant. This pose is not uncommon in depictions of Renaissance women, especially in the Northern Renaissance context (see, for example, A Bridal Couple in The Cleveland Museum of Art). The odd pose was adopted for practical purposes: full Renaissance skirting forced women to pick up their gowns when they walked. The gesture likewise illuminates the wearer’s moneyed status.

According to costume historian Ann Hollander, the notorious, seemingly pregnant silhouette touted by the woman in The Arnolfini Portrait (and countless other images of women created throughout the early modern period) connoted elegance and luxury on the part of the wearer and her male keeper (for the man it was a swelled midsection). The more dramatic a woman’s curves, the more real estate to show off exquisitely tailored fabrics. The lifting of skirts likewise provided a chance to further showcase wealth by revealing contrasting undergarments (such as the blue undergown worn by the woman in the Arnolfini Portrait).

While the woman’s gown does not display an actual pregnancy, it is possible that the controversial dress is coded with pregnancy and may be read as symbolic of women’s roles in the Renaissance, including motherhood. The woman’s ample costume does not conceal or describe a pregnancy; however, it is roomy enough to easily host a future one without the need for tailoring. Its green hue could also connote fecundity, as the color was widely associated with springtime and therefore fertility and fruitfulness in the period. Additionally, the gown is lined with ermine. Art historian Jacqueline Musacchio has argued that martins and weasels in portraits (either alive or skinned) may be symbolic of pregnancy or the hope for future pregnancy. It is no accident, therefore, that mid-fifteenth century Flemish haute couture (high fashion) suggests pregnancy.

Jan Van Eyck, Cloth gathered on the floor (detail), The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, tempera and oil on oak panel, 82.2 x 60 cm (National Gallery, London), photo: Dr. Steven Zucker CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

A new question

Perhaps the question we should be asking when considering the Arnolfini Portrait is not “is the female figure pregnant?” Instead, we can consider why the female figure appears to be pregnant. The persistent illusion asks us to consider Renaissance gender roles, as well as our own beliefs concerning depictions of women in pre-modern art. The woman in the green dress is not meant to be read as actually pregnant, yet—more significantly—she lived and died in a culture that expected near-constant pregnancy from women.

Notes:

[1] Diane Wolfthal, In and out of the Marital Bed: Seeing Sex in Renaissance Europe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), pp. 40–41.

Additional Resources:

This painting at The National Gallery

Victoria Finlay, Color: A Natural History of the Palette (1st Ballantine Books ed. New York: Ballantine Books, 2003).

Anne Hollander, Seeing through Clothes (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

Jacqueline Marie Musacchio, “Weasels and Pregnancy in Renaissance Italy,” Renaissance Studies 15, no. 2 (2001), pp. 172–87.

Diane Wolfthal, In and out of the Marital Bed: Seeing Sex in Renaissance Europe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”arnolfini,”]