Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of Lisa Gherardini (known as the Mona Lisa), c. 1503–19, oil on poplar panel, 77 x 53 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in the single most crowded room in the Louvre, but for good reason. This is the room that holds the “Mona Lisa” by Leonardo da Vinci. Without a doubt, the most famous painting in the world.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:14] Of course, it’s her smile that’s so famous today. It certainly is a smile that doesn’t clearly tell us what she’s feeling. It’s ambiguous.

Dr. Zucker: [0:24] I think it allows people to read into it in any way that they prefer.

Dr. Harris: [0:28] Sigmund Freud, for example, saw a combination of a maternal gaze, but also a gaze that was flirtatious. I think I do see both of those aspects here.

[0:40] This is a portrait of the wife of a Florentine merchant, and as we look out at the sea of people taking selfies in front of the Mona Lisa, it’s good to remember that only the elite could have their portrait painted during the Renaissance. This was an expensive proposition. And of course, you’d have to go and sit for the artist many times so that he could capture your likeness.

Dr. Zucker: [1:01] Because they were expensive, they were reserved for kings and queens and the nobility.

[1:06] What we see during the Renaissance is the growth of the merchant class. The fact that a wealthy merchant would hire Leonardo to paint his wife’s portrait is a reminder of the fortunes that are being made by traders, by bankers, and others during the Renaissance.

Dr. Harris: [1:20] Well, especially in the city of Florence, which was such an economic hub during the Renaissance. We know, in fact, that the patron of this painting was a cloth merchant.

Dr. Zucker: [1:29] This painting has quite a number of innovations, but one of the most important is that it’s half-length. Generally, portraits were busts, that is, from the chest up.

Dr. Harris: [1:38] This was an incredibly influential new formula for the portrait. If you think about the standard form of the portrait before this with the figure in profile, bust length, it’s a very static pose, very formal, very stiff.

[1:52] But as soon as Leonardo turned the head toward us, positioned the shoulders three-quarter toward us also, and included the hands, suddenly we had an image of a figure that was much more natural, someone who you could imagine having a conversation with.

[2:08] Portraits that included a background and that also included the hands did exist in the Northern Renaissance. But this is a new formula for Italy, and will be tremendously influential with artists like Raphael and others.

Dr. Zucker: [2:23] Another very influential aspect of this painting is a technique that Leonardo employed which is known as “sfumato.” That simply means “smoke.”

[2:30] What it refers to is the slightly hazy quality that Leonardo introduces to remove the sometimes sharp quality that existed in early Renaissance paintings, where each object looks too isolated. It’s an atmospheric quality that creates a sense of unity throughout the painting.

Dr. Harris: [2:47] And makes the figure appear to almost emerge out of the darkness. So we see that she’s seated on a chair in a loggia, [an] open porchway.

[2:57] We see on either side of her what look like the base of two columns. We don’t know if the painting was cut down and there were originally full columns on either side of her, but we do know that early copies of this painting do show those columns on either side of the figure.

Dr. Zucker: [3:14] There’s a lot about this painting that we don’t fully understand. This was a commission, and yet Leonardo kept the painting. He never delivered it to the man who commissioned it. Later in Leonardo’s life, when he moved to France, he brought the painting with him, which is why it’s now in the Louvre.

[3:28] One question that I think we should address is why is this the most famous image in the world.

Dr. Harris: [3:33] It reminds me of another very famous image of a woman that’s very ambiguous and mysterious. That’s “The Woman with a Pearl Earring” by Vermeer from more than a century later. Perhaps our culture has some fascination with images of mysterious women.

Dr. Zucker: [3:50] I think that’s probably an important part of it, but then I think fame grows on itself. In 1911, the painting was stolen, and it was headlines around the world. That accelerated its fame. It has become the subject of numerous other paintings by artists as diverse as Marcel Duchamp or Andy Warhol. This raises an interesting issue.

[4:09] Here’s a painting that was made for a private home, to exist in a domestic interior to celebrate a man’s wife or to celebrate a specific occasion, perhaps the birth of a child or the purchasing of a new home. But here it is instead in a huge gallery with hundreds of people, a painting that exists in millions of multiples around the world.

[4:30] It’s such an unexpected fate for what Leonardo surely saw as a relatively minor commission.

[4:36] [music]

Portraits were once rare

We live in a culture that is so saturated with images, it may be difficult to imagine a time when only the wealthiest people had their likeness captured. The wealthy merchants of renaissance Florence could commission a portrait, but even they would likely only have a single portrait painted during their lifetime. A portrait was about more than likeness, it spoke to status and position. In addition, portraits generally took a long time to paint, and the subject would commonly have to sit for hours or days, while the artist captured their likeness.

View of crowd surrounding Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of Lisa Gherardini (known as the Mona Lisa), c. 1503–19, oil on poplar panel, 77 x 53 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: -JvL-, CC BY 2.0)

The most recognized painting in the world

The Mona Lisa was originally this type of portrait, but over time its meaning has shifted and it has become an icon of the Renaissance—perhaps the most recognized painting in the world. The Mona Lisa is a likely a portrait of the wife of a Florentine merchant. For some reason however, the portrait was never delivered to its patron, and Leonardo kept it with him when he went to work for Francis I, the King of France.

Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of Lisa Gherardini (known as the Mona Lisa), c. 1503–19, oil on poplar panel, 77 x 53 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

The Mona Lisa’s mysterious smile has inspired many writers, singers, and painters. Here’s a passage about the Mona Lisa, written by the Victorian-era (19th-century) writer Walter Pater:

We all know the face and hands of the figure, set in its marble chair, in that circle of fantastic rocks, as in some faint light under sea. Perhaps of all ancient pictures time has chilled it least. The presence that thus rose so strangely beside the waters, is expressive of what in the ways of a thousand years men had come to desire. Hers is the head upon which all “the ends of the world are come,” and the eyelids are a little weary. It is a beauty wrought out from within upon the flesh, the deposit, little cell by cell, of strange thoughts and fantastic reveries and exquisite passions. Set it for a moment beside one of those white Greek goddesses or beautiful women of antiquity, and how would they be troubled by this beauty, into which the soul with all its maladies has passed!

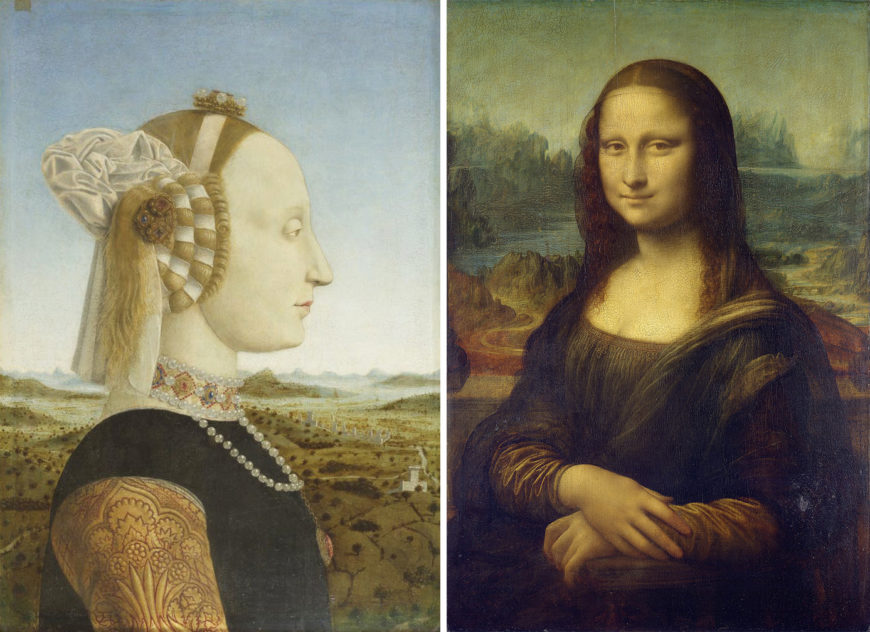

Left: Piero della Francesca, Portrait of Battista Sforza, c. 1465–66, tempera on panel (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence); right: Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of Lisa Gherardini (known as the Mona Lisa), c. 1503–19, oil on poplar panel, 77 x 53 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Piero della Francesca’s Portrait of Battista Sforza is typical of portraits during the Early Renaissance (before Leonardo); figures were often painted in strict profile, and cut off at the bust. Often the figure was posed in front of a birds-eye view of a landscape.

A new formula

Hans Memling, Portrait of a Young Man at Prayer, c. 1485–94, oil on oak panel (Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid)

With Leonardo’s portrait, the face is nearly frontal, the shoulders are turned three-quarters toward the viewer, and the hands are included in the image.

Leonardo uses his characteristic sfumato—a smokey haziness—to soften outlines and create an atmospheric effect around the figure. When a figure is in profile, we have no real sense of who she is, and there is no sense of engagement. With the face turned toward us, however, we get a sense of the personality of the sitter.

Northern Renaissance artists such as Hans Memling (see the Portrait of a Young Man at Prayer) had already created portraits of figures in positions similar to the Mona Lisa. Memling had even located them in believable spaces. Leonardo combined these Northern innovations with Italian painting’s understanding of the three dimensionality of the body and the perspectival treatment of the surrounding space.

Left: Unknown, Mona Lisa, c. 1503–05, oil on panel (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid); right: Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of Lisa Gherardini (known as the Mona Lisa), c. 1503–19, oil on poplar panel, 77 x 53 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

A recent discovery

An important copy of the Mona Lisa was recently discovered in the collection of the Prado in Madrid. The background had been painted over, but when the painting was cleaned, scientific analysis revealed that the copy was likely painted by another artist who sat beside Leonardo and copied his work, brush-stroke by brush-stroke. The copy gives us an idea of what the Mona Lisa might look like if layers of yellowed varnish were removed.