El Escorial, begun 1563, near Madrid, Spain (photo: Vvlacenko, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Located near Madrid, San Lorenzo de El Escorial is an imposing architectural complex that is arguably the most ambitious monument constructed during the Renaissance in Spain. Construction started in 1563 after King Philip II of Spain decided to commission a funerary monument for his father, the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. But Philip II desired an even more complicated structure that would also function as a palace and monastery. By the time construction ended in 1584, the complex included not only these, but a church and college as well. A library was also added in 1592. The project was so complex that it took more than a decade to complete, and approximately a thousand people worked on it during its peak construction period.

A new Spanish severity

El Escorial is often described as severe or somber in appearance, with a symmetrically organized plan and a largely unornamented exterior. In its day, this was remarkable because it broke with architectural styles popular on the Iberian Peninsula, including the highly decorative Plateresque style, which was influenced by the ornate designs of silverwork.

Platereresque style, University of Salamanca, façade, begun c. 1415 (photo: Zarateman, public domain)

The facade of the University of Salamanca, for instance, is a veritable feast for the eyes, with floral imagery, twisting vines, and medallions decorating the surface. El Escorial has none of this elaborate ornamentation.

The massive complex has four storeys, with large, rectangular towers at each corner. There are eleven courtyards, as well as three smaller “service” courts, and several gardens. Classical orders of columns punctuate the exterior, with massive, simple Doric columns on the façade. While there is little decorative or figural ornamentation, the west façade that marks the entrance to the Courtyard of the Kings (Patio de los Reyes) displays St. Lawrence (San Lorenzo) above the royal coat of arms, and the basilica’s facade includes six Old Testament kings towering above the first level.

El Escorial, begun 1563. Left: west façade with St. Lawrence (San Lorenzo) and the royal coat of arms (photo: Jebulon, public domain); Right: basilica façade with six Old Testament kings (photo: J. B. Monegro, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The grid plan

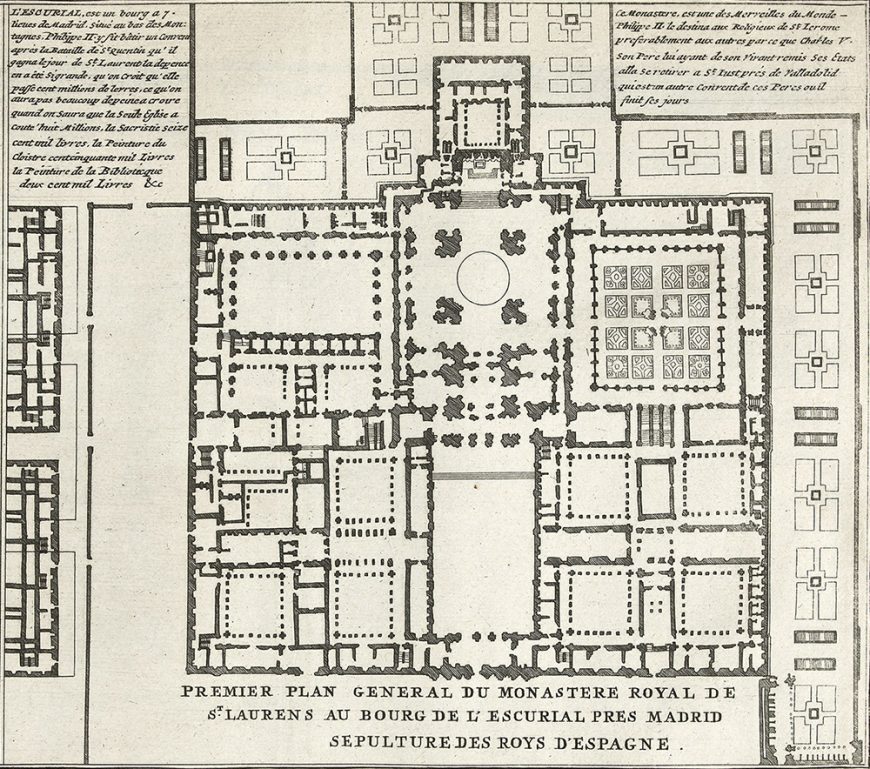

The original layout of the complex was on a grid (sometimes referred to as a gridiron) plan laid out by Juan Bautista de Toledo, a student of Michelangelo who aided in the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. A grid plan suggests order and balance, clarity and unity. At El Escorial, some suggest that the grid plan possibly relates to the grill upon which St. Lawrence (San Lorenzo in Spanish) was martyred. Most Spanish cities on the Iberian Peninsula did not use the grid plan, in large part because they were older cities whose streets were already laid out. However, Philip II issued edicts in the sixteenth century that affected the construction of towns and cities in the Spanish viceroyalties that specified grid plans. This suggests a broader trend in Spain and its territories during the Renaissance of a return to cities laid out clearly and consistently—a nod to ancient Roman building practices.

Ground plan of El Escorial, 1726, etching, 22.7 x 33.2 cm (Rijksmuseum)

A second architect, Juan de Herrera, completed the project after Toledo’s death in 1567. Herrera reportedly met with Philip II often to consult on the project, and the king appointed him as his royal architect towards the end of the 1570s. Herrera is known for his “severe” classicism, which was influenced by the Italian architectural forms of architects such as Sebastiano Serlio, Giacomo da Vignola, and Giulio Romano, whose work he observed on his travels to Italy. His design for El Escorial may have been especially influenced by Romano’s Palazzo Te in Mantua, which also incorporated classicizing architectural elements. El Escorial’s severe style is sometimes referred to as “Herreresque” in honor of Herrera.

Library, El Escorial (photo: photongatherer, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Art at El Escorial

Basilica of El Escorial (photo: photogatherer, CC BY-NC 2.0)

While the exterior is restrained in its decoration, many areas of the interior are elaborately decorated. Inside the basilica, more depictions of kings and saints await visitors. Frescoes adorn many of the surfaces, such as the walls of the library. Despite its highly decorative qualities, El Escorial’s interior is harmonious, with the ornamentation carefully planned to create a visually unified space.

Pellegrino Tibaldi, The Martyrdom of St. Lawrence, 1592, oil on canvas, 419 x 315 cm (Basilica El Escorial)

Artists from different parts of Europe were hired to adorn the interior. Federico Zuccaro and Pellegrino Tibaldi were two Italian painters paid to complete frescoes and other paintings. Tibaldi’s Martyrdom of St. Lawrence on the main altarpiece in the basilica showcases the influence of Michelangelo, with its grandiose figures displaying well-defined musculature. We also find works by Claudio Coello, Luca Giordano, and El Greco. The latter produced The Martyrdom of St. Maurice for El Escorial in 1582, but Philip II apparently rejected it on claims that the the foreground figures were the focus of the composition.

During Philip II’s reign, El Escorial came to house many artworks, including some by Titian and others by Flemish painters like Hieronymous Bosch. The king eventually owned roughly twenty-six paintings by Bosch, many of which hung in El Escorial, including the artist’s famous Garden of Earthly Delights. Works that formed part of the royal collection at El Escorial eventually entered the Prado Museum’s collection.

El Escorial, begun 1563, near Madrid, Spain (photo: Turismo Madrid Consorcio Turístico, CC BY 2.0)

A symbol of Imperial Spain

Philip encouraged those visiting him at court to journey to El Escorial. One particularly fascinating example dates to 1584 when Japanese nobles and their Portuguese Jesuit guide visited Philip II in Madrid, at which point the Spanish king brought them to El Escorial to delight in his project and hopefully impress them with its magnificence. Apparently it worked, as one record states that the Japanese nobles claimed it was “so magnificent a thing, whose like we have never seen or expected to see.”[1] One can imagine that the severe classicizing style combined with a grid plan helped to establish Philip II as akin to the great Roman emperors of the past, as well as a formidable imperial ruler with refined taste during the Renaissance.

[1] Henry Kamen, The Escorial: Art and Power in the Renaissance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 84).

Additional resources: