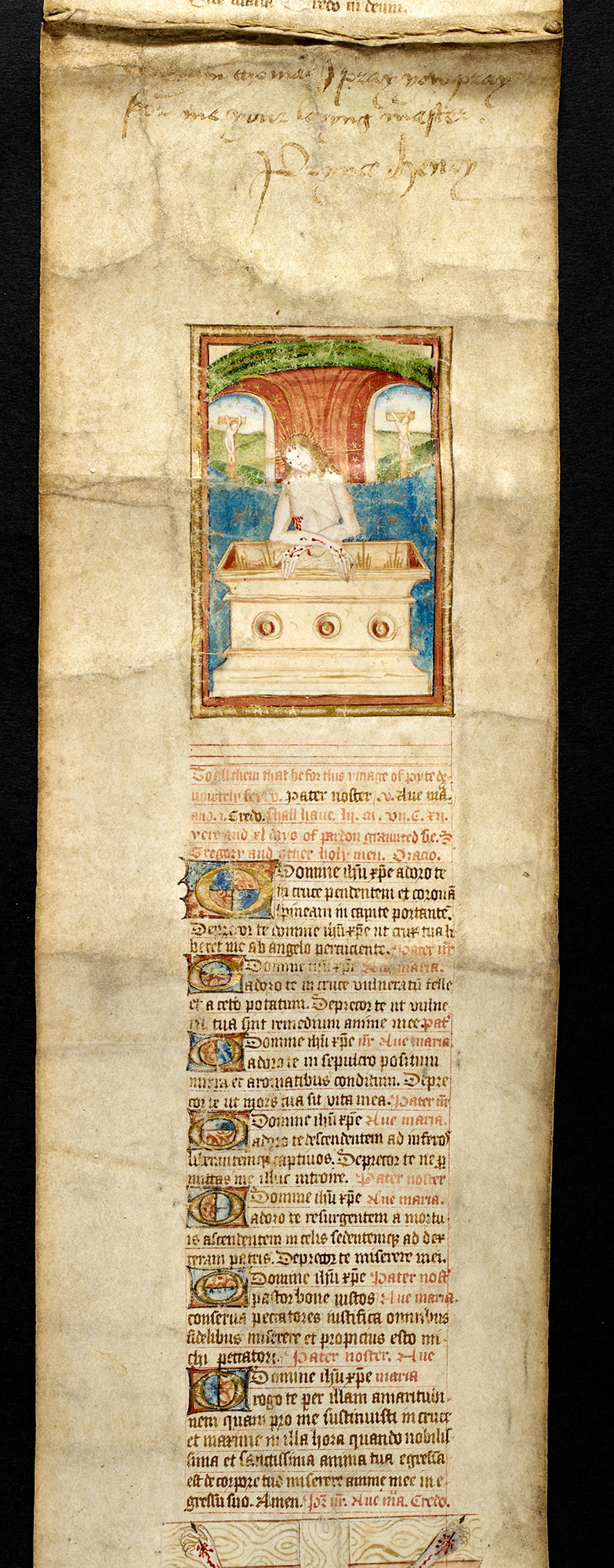

Henry VIII was brought up a devout Catholic. Before he became king, he had in his possession a prayer scroll containing illuminations of the Trinity, the crucified Christ, the Instruments of the Passion and several martyred saints. Latin prayers were placed on each side of the images, together with English rubrics (instructions) that explained how the prayers could offer protection from earthly dangers or the remission of time in Purgatory. Sacred texts of this kind were common as part of the devotional practices of late-medieval England. Owners of the scrolls recited the prayers, contemplated the images and touched the material object so as to become closer to the divine and earn heavenly reward in the afterlife. Henry’s inscription on the prayer scroll suggests that he used it for these holy purposes and accepted the theological teachings that lay behind them.

Henry VIII’s prayer scroll. Measuring over three metres in length, this roll contains prayers in Latin and English and fourteen illuminated images, which include martyred saints, St George slaying the dragon, and Christ’s Passion. Prayer-roll of Henry VIII, c. 1485–1509, parchment roll, 335.5 x 12 cm (The British Library)

Henry’s Catholic worship was typical of the era. Along with the prayer scroll, he also held fast to the belief that purchasing papal indulgences could pardon sin and shorten time in Purgatory; a popular practice at the time. In 1521 he and Katherine of Aragon received a ‘plenary indulgence’ from Pope Clement VII, which was tied to them carrying out an annual pilgrimage to a major shrine. When Martin Luther’s protest against the sale of indulgences sparked off the German Reformation, Henry defended the practice in his rebuttal, ‘Defence of the Seven Sacraments’.

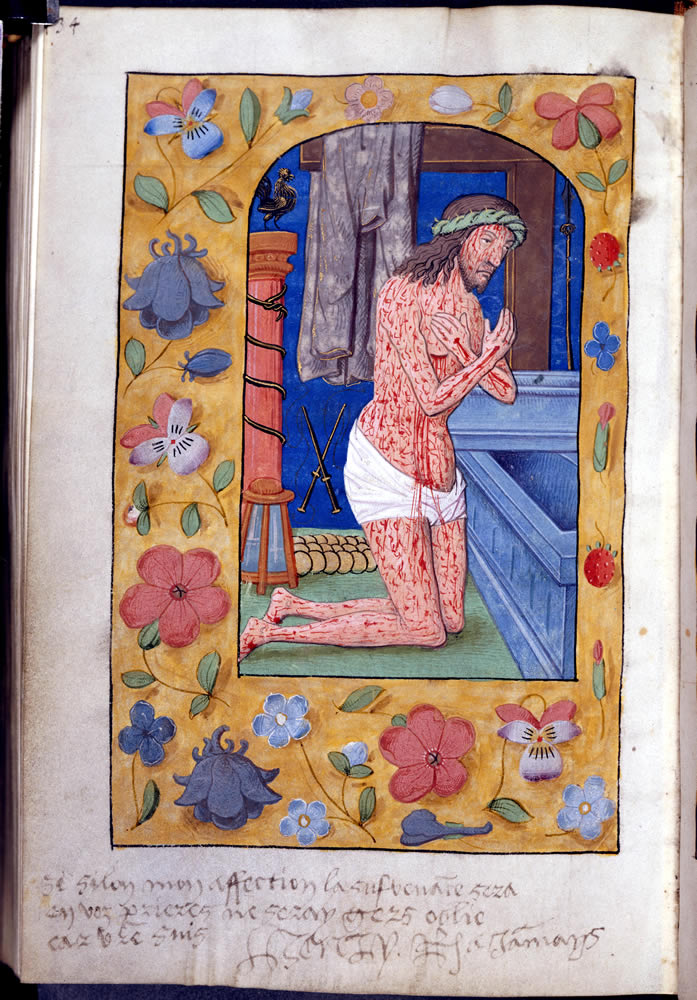

The British Library also holds another text that shines a light on Henry’s piety; a Book of Hours that has secret messages exchanged between Henry and Anne Boleyn written in the margins. Books of Hours were common sacred texts for laypeople’s use. As compendia of prayers and devotional texts, the books had at their core the ‘Office of the Virgin Mary’, set prayers addressed to the Mother of Christ and recited daily at eight fixed hours. Mary, it was hoped, would act as an intercessor between the owner and God. The pages were often beautifully illustrated by the best artists of the day. Those for the nobility were richly illuminated with precious gold leaf and lapis lazuli. But, at some time around 1528, Anne and Henry employed his book for less spiritual purposes. At the foot of the folio showing the Man of Sorrows, Henry inscribed a lover’s message for Anne in French: ‘If you remember my love in your prayers as strongly as I adore you, I shall hardly be forgotten, for I am yours. Henry R. forever.’ Anne chose to pen her response on a page which showed the Annunciation, so suggesting her wish and power to give the king a son. She wrote in English: ‘Be daly prove you shalle me fynde to be to you bothe lovynge and kynde’.

Book of Hours once belonged to Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII’s second wife. With unique historical importance, this manuscript is a rare example of lovers using a religious book to exchange flirtatious messages. Book of Hours, Use of Sarum (”Anne Boleyn”s Book of Hours”), c. 1500, parchment, 13.5 x 19.5 cm (The British Library)

The prayers in these late-medieval sacred books and scrolls were often in Latin to signify that all Western Christians were part of the Roman Catholic Church. However, Henry formally broke with the Pope and the Roman Church after Pope Clement VII refused to grant him an annulment of his marriage to Katherine of Aragon so that he could wed Anne. His appeal for an annulment was on the grounds that their union contravened the scriptures, citing Leviticus 20. 21, which prohibits a man from marrying his brother’s widow.

In 1533 the English Parliament passed the Act in Restraint of Appeals, which denied papal jurisdiction in England and ended appeals of court cases to Rome. The 1534 Act of Supremacy then recognised the king as the Supreme Head of the Church in England with ‘full power and authority’ to ‘reform’ the institution and ‘amend’ all errors and heresies. Henry and his newly-appointed ‘Vice Gerent in Spiritual Affairs’, Thomas Cromwell, immediately embarked upon a programme of reform. Cromwell’s Injunctions of 1536, and 1538 attacked idolatry, pilgrimages and other ‘superstitions’. The lesser monasteries were closed in 1536 and the remaining monasteries were dissolved over the next few years. Those men and women who resisted the closures were imprisoned or hanged.

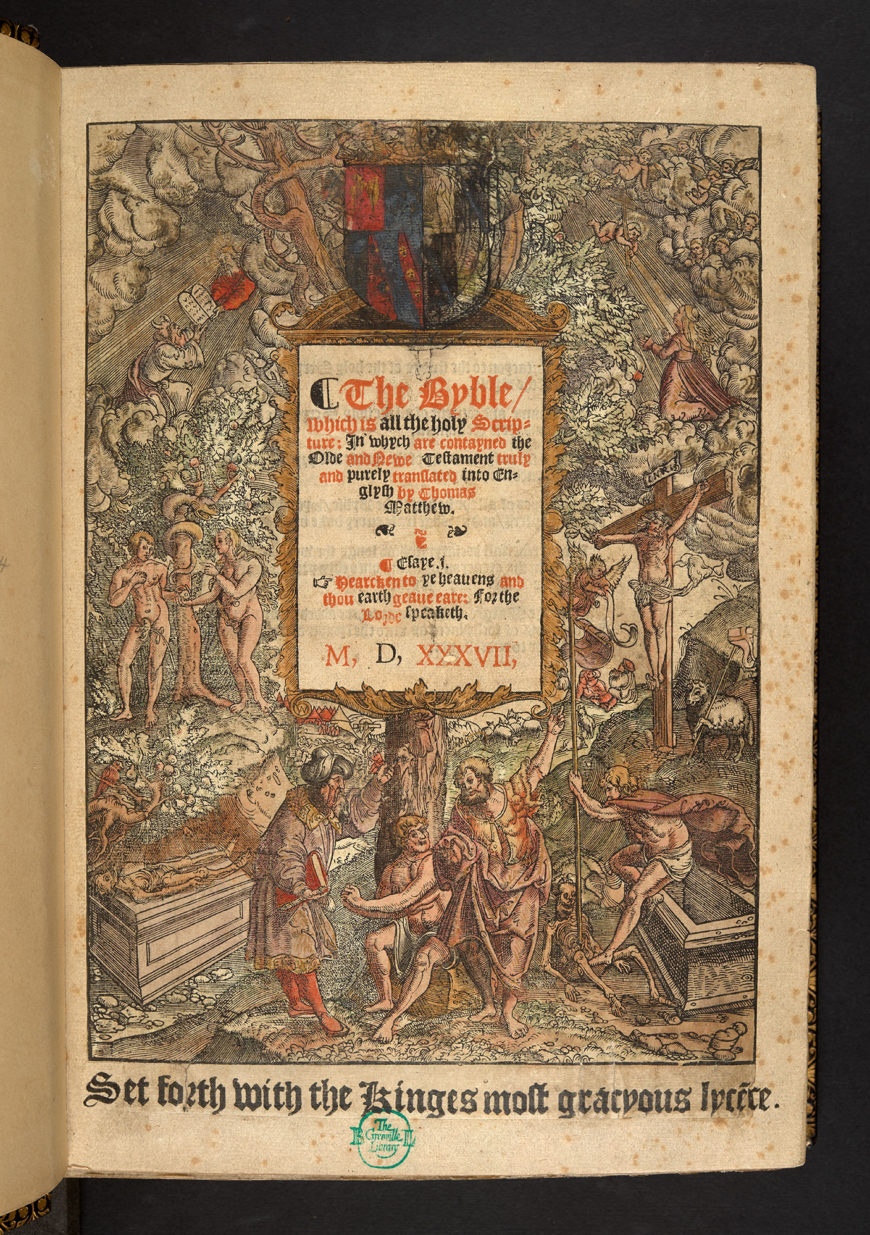

Although Henry rejected Martin Luther’s theology of justification by faith alone, he did accept the German reformer’s insistence upon the supremacy of Scripture. After all, the ‘Word of God’ (Leviticus 20.21) had justified the annulment of his first marriage. Consequently, encouraged by Cromwell and Archbishop Thomas Cranmer of Canterbury, Henry authorised an English Bible that could be read by the laity as well as the clergy. At this time the best printed translation of the New Testament in English was by William Tyndale, who was a Lutheran burned in Antwerp in 1536. However, the king and his more conservative bishops refused to entertain the thought of publishing any work of the convicted heretic. Instead, two other Bibles received a royal licence.

![Miles Coverdale [translator], Biblia. The Bible, tha[t] is, the holy Scripture of t[he] Olde and New Testament, faithfully and truly translated out of Douche and Latyn in to Englishe [by Miles Coverdale, afterwards Bishop of Exeter. With woodcuts]. B.L., October 4, 1535 (The British Library)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Coverdale-Bible-C_18_b_8-tp-870x1368.jpeg)

A 1535 copy of Miles Coverdale’s translation of the Bible, a large lectern size Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments as well as the Apocrypha. Miles Coverdale [translator], Biblia. The Bible, tha[t] is, the holy Scripture of t[he] Olde and New Testament, faithfully and truly translated out of Douche and Latyn in to Englishe [by Miles Coverdale, afterwards Bishop of Exeter. With woodcuts]. B.L., October 4, 1535 (The British Library)

A 1537 copy of ‘Matthew’s Bible’, printed in Antwerp. The Byble, which is all the holy Scripture: in whych are contayned the Olde and Newe Testament truly and purely translated into Englysh by Thomas Matthew., 1537, printed book (The British Library)

Neither Bible was thought entirely satisfactory. So in 1538 Cranmer and Cromwell commissioned Coverdale to revise the ‘Matthew Bible’ and produce a better translation. The new work was intended to be the realm’s single authoritative Bible. In accordance with Cromwell’s 1538 Injunctions, it was ordered to be chained to lecterns in every cathedral and parish church for communal and public reading by clergy and parishioners alike. Because of its large size, the book became known as the ‘Great Bible’. Its woodcut title page visually communicated the royal supremacy. Receiving the Word directly from God, the enthroned king at the top of the page passes the sacred text of the Bible to his spiritual lords on his right and lay lords on his left. From there, the verbum dei (‘Word of God’) descends to be read to the local parish congregation and even to reach prisoners in jail.

![Thomas Cranmer, The Byble in Englyshe, that is to saye the contēt of al the holy scrypture ... with a prologe therinto, made by ... Thomas [Cranmer] archbysshop of Cantorbury, This is the Byble apoynted to the vse of the churches. [With woodcuts.] B.L., 1540 (The British Library)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/The-Great-Bible-870x1293.jpeg)

Henry VIII’s ‘Great Bible’, based on an earlier version begun illegally by William Tyndale and adapted by Miles Coverdale in 1535. Thomas Cranmer, The Byble in Englyshe, that is to saye the contēt of al the holy scrypture … with a prologe therinto, made by … Thomas [Cranmer] archbysshop of Cantorbury, This is the Byble apoynted to the vse of the churches. [With woodcuts.] B.L., 1540 (The British Library)

New Bible, old doctrines

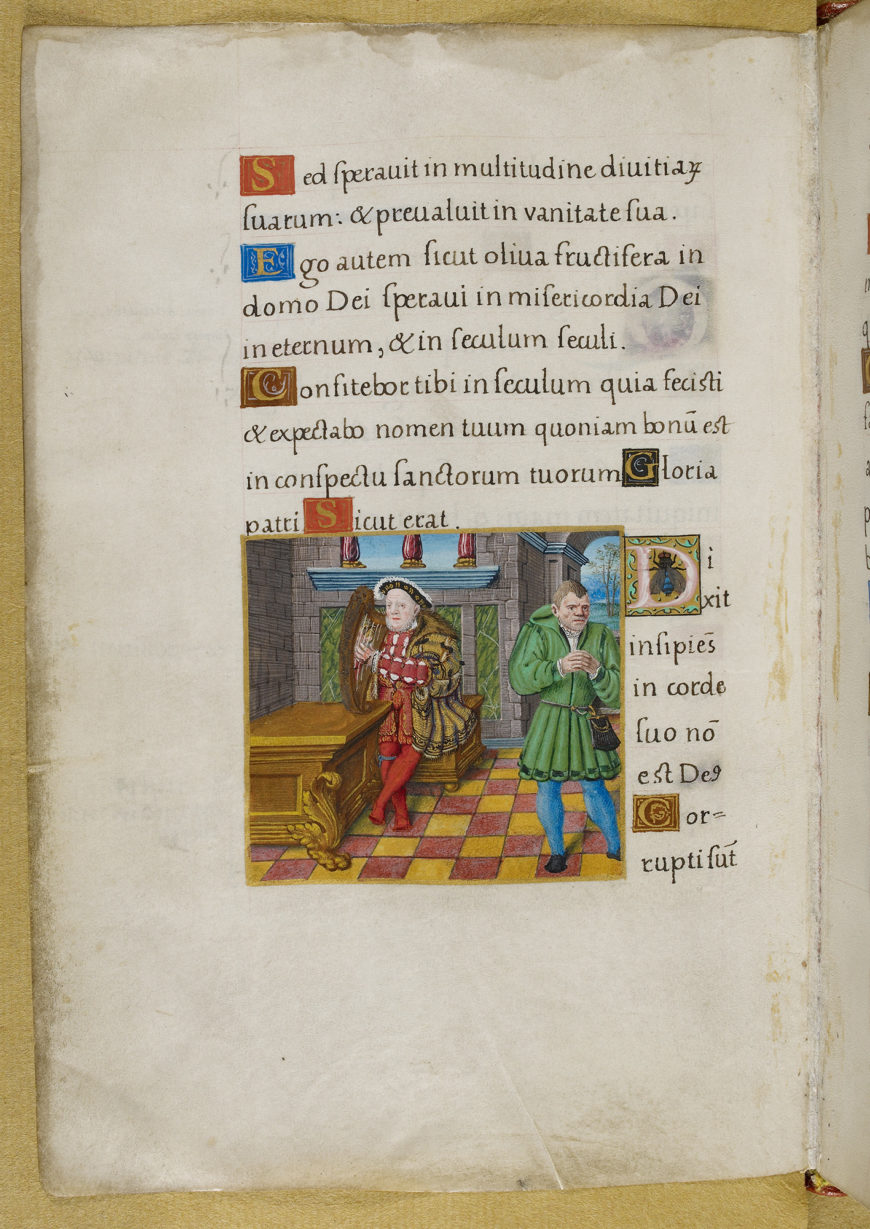

The Great Bible was printed in 1539. That same year Henry clarified the beliefs of his Church in ‘An Act Abolishing Diversity in Opinions’, better known as ‘The Act of Six Articles’. This statute laid down Henry’s position on some of the key issues dividing conservatives and evangelicals in England. Although he tried to find a path between the extremes of Roman Catholicism and Lutheranism by following what he saw as a policy of balance, the king took up a conservative position on virtually all of the controversial points. On the Mass, the Act affirmed transubstantiation, elucidating that ‘after the consecration, there remaineth no substance of bread or wine, nor any other substance, but the substance of Christ, God and man’. Other clauses denied that communion in both kinds was necessary, upheld clerical celibacy, permitted private Masses (those celebrated by a priest alone) and deemed auricular confession necessary. A few years later Henry shifted his position somewhat. The 1543 ‘Necessary Doctrine and Erudition for Any Christian Man’, known as the ‘King’s Book’ (another formulary of faith), instructed his subjects ‘to abstain from the name of Purgatory’ and questioned the efficacy of prayers for the dead. Nonetheless, the book unambiguously rejected justification by faith alone and reaffirmed transubstantiation, two positions which contradicted Luther’s teachings. When the king died in January 1547 England was therefore doctrinally Catholic despite the rejection of papal supremacy. As for Henry’s personal convictions, he remained conventionally pious. He continued his private devotions in Latin; in fact one of the last books he commissioned was a beautiful Latin psalter, written and illuminated by the French émigré Jean Mallard. Four illuminations depict Henry; one of them showed him reading the book in his bedchamber while another showed him as David playing the harp (as in I Samuel 16.14-23). Evidently, he identified with the Old Testament theocratic king. As was his wont, Henry scribbled notes in the book. Some of them explored themes such as the contrast between the blessed and the wicked, divine judgement, kingship and the vanity of worldly goods.

Commissioned by King Henry VIII, this Psalter (Book of Psalms) gives an insight into the king’s self-assurance as divine ruler of England. Jean Maillart (or Mallard), Psalter (‘The Psalter of Henry VIII’), c. 1540–1541, parchment codex, 20.5 x 14 cm (The British Library)

English devotional manuscripts

While Henry continued, it seems, to prefer Latin for his sacred texts, some of his subjects were turning to works in English for their devotions. In 1539 an English edition of Wolfgang Capito’s Precationes Christianæ ad Imitationem Psalmorum was printed in London. The translator was Richard Taverner, who was working for Cromwell during the 1530s and translating works of both Erasmus and Lutherans. A manuscript containing a selection of psalms and prayers from the translated Precationes was owned by Anne, Countess of Hertford, who was the second wife of Henry’s brother-in-law Edward Seymour (to be created 1st Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector on Henry’s death). Known as ‘Taverner’s prayer book’, the small book is richly decorated on each page with a full-page border in colours and gold, while small illuminated initials mark the start of each prayer and psalm. Extracts from Taverner’s translation were also put together in a manuscript prayer-book owned by Henry’s great niece, Lady Jane Grey, who became noted for her Protestant piety during the next reign. The prayers, however, do not assert any particular confessional position. Some traditionalist prayers are included, but in none of them is there any reference to Purgatory.

![Richard Taverner [translator], Prayer book ('The Taverner Prayer Book'), c. 1540, parchment, 7.0 x 5.2 cm (The British Library)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Taverner-prayer-book-add_ms_88991_f006v-870x1171.jpeg)

This tiny, richly decorated book of Psalms and prayers in English was most likely made for the noblewoman and literary patron Anne Seymour (née Stanhope), Countess of Hertford and later Duchess of Somerset (c. 1510–1587). Richard Taverner [translator], Prayer book (‘The Taverner Prayer Book’), c. 1540, parchment, 7.0 x 5.2 cm (The British Library)

This tiny Book of Prayers, written in English, is probably that used by Lady Jane Grey on the scaffold at her execution in 1554. Prayer book (‘Lady Jane Grey’s Prayer book), c. 1539–44, parchment codex, 8.5 x 7.0 cm (The British Library)

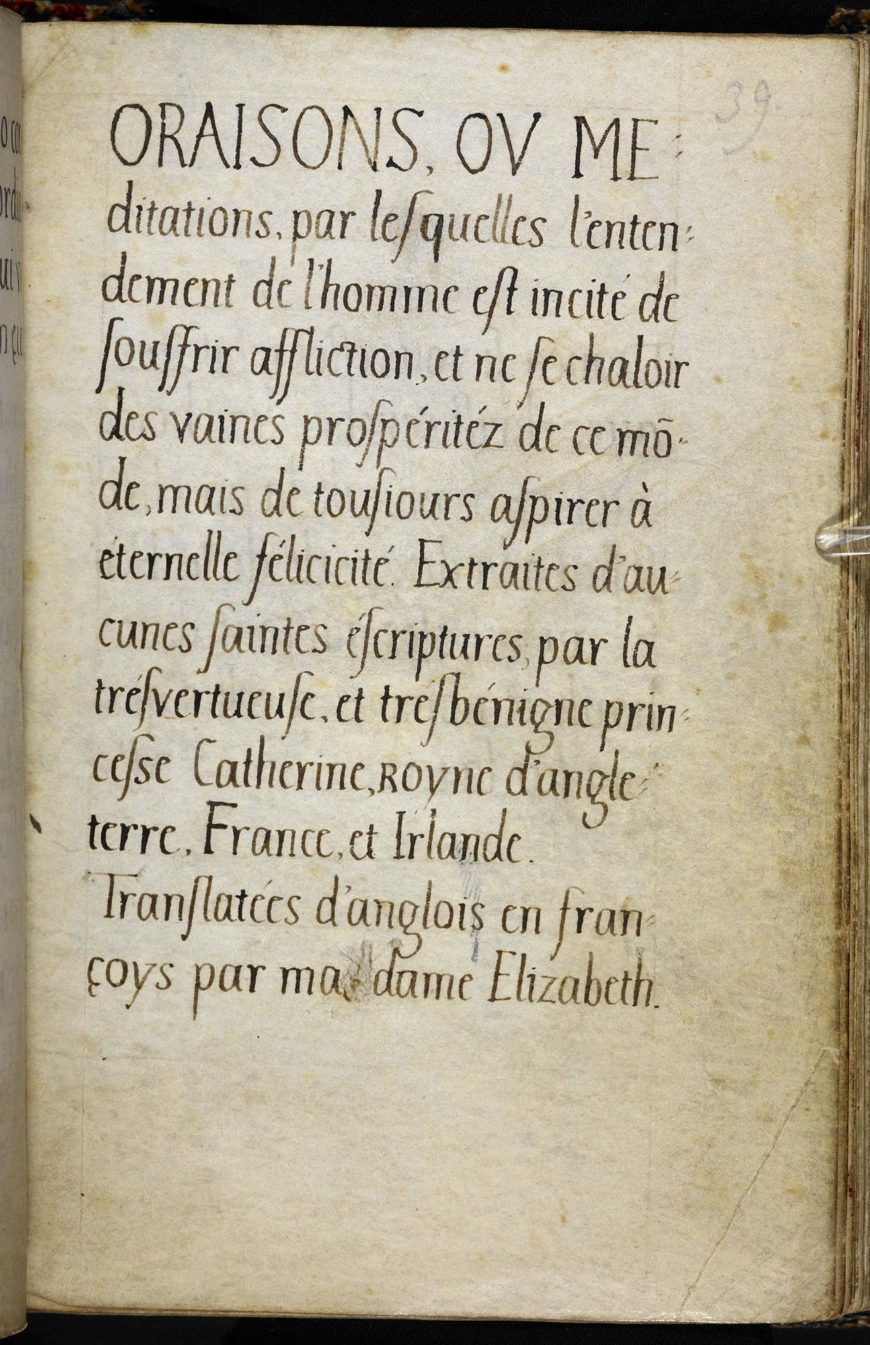

Henry’s last wife, Katherine Parr, shared the reformist tendencies of her friend, the Countess of Hertford. She almost certainly had a spiritual influence on both the king’s younger daughter Elizabeth and Lady Jane Grey when they each spent time in her household. Katherine wrote several devotional works while queen. Her reworking of Thomas à Kempis’ De Imitatione Christi (from an English edition) was printed in 1545 under her own name (the first book printed under the name of a woman in English). To compliment her stepmother, the twelve-year-old Elizabeth gave the king her own trilingual translation (Latin, French and Italian) of the work as a New Year’s Day gift for 1546.

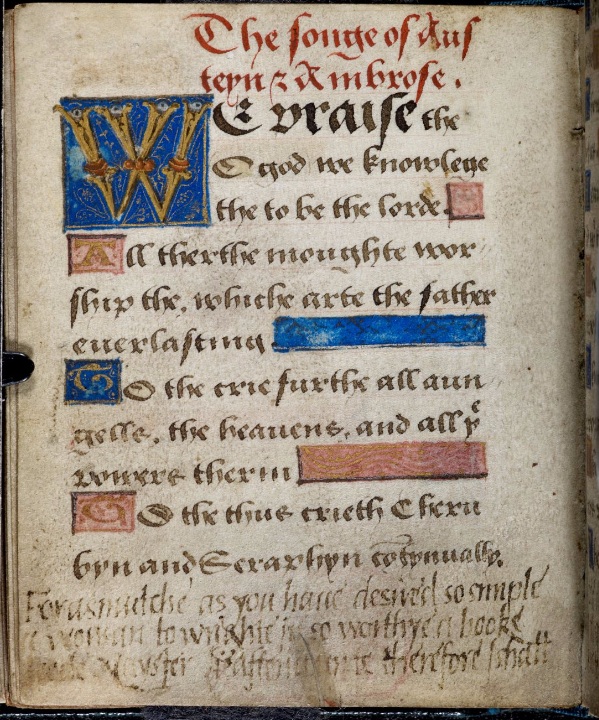

In December 1545, King Henry VIII was presented with this carefully embroidered volume as a New Year’s gift. The prayer-book had been assembled by his twelve-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, who would herself ascend to the throne in 1558. Queen Elizabeth I, Prayers and meditations (the ‘Prayerbook of Princess Elizabeth’), 1545, parchment codex, 14 x 10 cm (The British Library)

Paving the way for Protestantism

Henry VIII’s Reformation had begun an attack on sacred objects, such as saints’ relics and shrines. Some sacred texts were also defaced or destroyed, especially those which venerated popes or St Thomas Becket, who had stood up to King Henry II. Many manuscripts and books in monastic libraries were trashed or dispersed during the dissolutions, although the antiquarian John Leland managed to collect and conserve a large number for the king. Despite this, sacred texts remained an important part of English religious culture. Indeed more of them began to appear in English, and of course several English Bibles came into circulation. However, for those who were evangelical or Protestants, the works contained no mention of purgatory and were not be handled as holy objects in themselves. The ground was being laid for the full-blown Protestantism introduced on Henry’s death by Archbishop Cranmer and Lord Protector Somerset.

Written by Susan Doran

Susan Doran FRHS is Professor of Early Modern History at the University of Oxford and Senior Research Fellow at Jesus College, Oxford, and St Benet’s Hall, Oxford. She specialises in the high politics, religion and culture of the 16th and early-17th centuries. She edited the catalogue of the British Library exhibition Henry VIII: Man and Monarch in 2009, and her book Elizabeth I and her Circle first appeared in 2015. Since then she has been working on the early years of James I’s reign.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

Originally published by The British Library.