Vlad III (detail), Portrait of Vlad III Dracula (Ambras Portrait), second half of the 16th century, oil on canvas, 60 x 50 cm (Ambras Castle, part of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

No other historical figure from Eastern Europe has enjoyed as much popularity in the historical record and the modern imagination as Vlad III Dracula. He was prince of Wallachia on three separate occasions during the second half of the 15th century (Oct–Nov 1448; 1456–62; and Nov–Dec 1476).

This was a time of great turmoil across Eastern Europe, following the capture of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453 and the subsequent fall of the Byzantine Empire. Although many of the details of Vlad’s life and deeds remain open to interpretation, several surviving visual and textual sources offer a complex picture of this medieval hero who inspired the modern vampire.

Portrait of Vlad III Dracula (Ambras Portrait), second half of the 16th century, oil on canvas, 60 x 50 cm (Ambras Castle, part of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

This portrait (commonly known as the Ambras Portrait) preserves an iconic image of Vlad III Dracula. Completed several decades after his death and supposedly based on a now-lost original, this painting shows the Wallachian ruler’s bust in three-quarter view and dressed in a red velvet coat with gold buttons and a large fur collar. His elaborate headdress is lined with pearls, a large central gem, and gold accents. His appearance is stern, with large, piercing eyes, arched eyebrows, an aquiline nose, long curly hair, and a prominent mustache. In this painting, the “Dux Balachie” (or ruler of Wallachia)—as the portrait was described in the inventory of Archduke Ferdinand in 1596—is shown as a respectable, yet stern, figure.

The portrait seems to match the only extant written description of Vlad, penned by Niccolò Modrussa (Modruš)—a papal legate at the court in Buda while Vlad was in captivity there for more than a decade, from 1462–74. Modrussa’s description reads:

[Vlad] was not very tall, but very stocky and strong, with a cold and terrible appearance, a strong and aquiline nose, swollen nostrils, a thin and reddish face in which the very long eyelashes framed large wide-open green eyes; the bushy black eyebrows made them appear threatening. His face and chin were shaven, but for a mustache. The swollen temples increased the bulk of his head. A bull’s neck connected [with] his head from which black curly locks hung on his wide-shouldered person. Radu R. Florescu and Raymond T. McNally, Dracula, Prince of Many Faces, 1989 [1]

The Ambras Portrait reflects these details, arguably confirming key features of the appearance of Vlad III.

Gentile Bellini, The Sultan Mehmed II, 1480, oil on canvas, 69.9 x 52.1 cm (The National Gallery, London)

In the guise of Vlad

In its artistic choices and mode of execution, the Ambras Portrait recalls the famous portrait of the Ottoman ruler Mehmed II by Gentile Bellini. Both portraits feature their sitters in similar positions set against a dark, ambiguous background, as well as garbed in a red mantle with a broad fur collar and elaborate headdress. Both portraits are successful in highlighting the key features and high status of the sitters. Bellini’s painting includes additional details like the delicately carved arch and decorated ledge in the foreground, which further frame and define Mehmed’s status, as well as the gold crowns in the upper portions of the panel, which represent the sultan’s newly-conquered cities: Constantinople, Iconium, and Trebizond.

Vlad’s appearance in the Ambras Portrait was also repeated in several other visual sources. In one mid-15th-century painting, the Roman official who condemned Christ appears in the guise of Vlad. Vlad’s figure is therefore associated with the torture and suffering of Christ in the Christian narrative of Pontius Pilate, drawing on the stereotypes that circulated during his reign and beyond. Moreover, the only full-length portrait of Vlad is found in an oil painting of c. 1700. The anonymous artist painted Vlad according to the Ambras Portrait, but completed his look with a long belted coat, a mace, and a sword. The accompanying inscription clarifies the identity of the figure: “Dracula Vaida [Voda] Prince and Voivode of Transalpine Wallachia, the most feared enemy of the Turks 1466.”

Left: Christ before Pontius Pilate (in the guise of Vlad Dracula), mid-15th century, tempera on wood, 83.5 x 51.5 cm (National Gallery of Slovenia, Ljubljana); right: Portrait of Vlad III Dracula, c. 1700, oil on canvas, 218 x 130 cm (Forchtenstein Castle, Austria)

Narratives of fear

Vlad was not only feared by his enemies, but also by his people and those in Wallachia’s neighboring regions. Shortly after his death in the winter of 1476/1477, numerous stories of his gruesome deeds began circulating across Europe in printed media. The so-called Geschichte Dracole Wayda pamphlets were used to spread stories about the atrocities Vlad had committed during his reign. Several of the accounts include the following brief narratives:

He had a great cauldron made, and over it [were placed] boards with holes, and he had people’s heads shoved through there, and thus he had them imprisoned. And he had the cauldron filled with water, and a great fire made under it. And thus he had the people scream miserably until they were boiled to death.

He had people ground to death on a grindstone, and he did many more inhumane things, which people tell of him.

He had a good meal prepared for all the beggars in his land. After the meal, he had them locked up in the barn in which they had eaten, and burned them all. He felt they were eating the people’s food for free and could not repay it. Dracole Wayda pamphlet, c. 1488 [2]

Accounts like these circulated through printed pamphlets, especially in the period between the 1480s and the 1530s. Fourteen versions of these pamphlets have survived, and they each include a woodcut of the Wallachian ruler (sometimes colored), which recalls the key features of the Ambras Portrait.

Left: Portrait of Vlad III in Dracole Wayda, c. 1488, colored woodcut from a pamphlet printed in Nuremberg (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich); right: Portrait of Vlad III in Dracole Wayda, c. 1491, woodcut from a pamphlet printed in Bamberg (British Library, London)

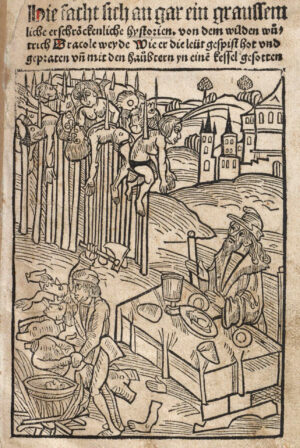

Several of the pamphlets also include a narrative vignette that accompanies this account: “… Dracula rested near the chapel of Saint James [in the vicinity of Brașov, a town in Transylvania]. He had the suburbs burned. And as the day came, in early morning, he had women and men, young and old, impaled near the chapel and around the hill, and he sat amidst [them], and ate his morning meal with joy.” This story underscores Vlad’s cruelty and indifference, which likely sent chilling messages to all those who encountered him through such sources. Although likely exaggerated, these accounts present Vlad as an immoral monster who spared no one. The lack of narrative coherence or chronology in these brief stories, which offer just a series of anecdotes with horrific details, contributed to the dissemination across Europe of a certain, otherworldly image of the Wallachian ruler.

Vlad III dining among a forest of the impaled, 1500, woodcut from pamphlet, printed by Matthias Hupnuff in Strasbourg (Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg)

The purpose of these pamphlets, according to one hypothesis, was to enlist the support of German towns in the struggles of the Transylvanian German Saxons. The German Saxons settled in regions of the Carpathian Mountains, mainly in Transylvania, beginning in the 12th century, and repeatedly suffered and were oppressed by the local communities. Vlad had many conflicts with the Transylvanian merchants during his reign, which often resulted in struggle and death for those who opposed him. Another hypothesis suggests that these stories emerged as part of a propaganda campaign while Vlad was captive, for more than a decade, at the Hungarian court (his captivity began in 1462). Such accounts certainly paint Vlad as a ruthless tyrant and enemy of the people.

In these sources, moreover, Vlad is demonized and “othered.” But what stands out is the cruelty of his deeds, and especially the acts of killing and impaling. The latter, a barbarous method of punishment, has a long history dating to antiquity. During the 15th century, impaling became a signifier of the vicious “East” in general (i.e., Eastern Europe and the Ottoman Empire) and intimately tied to the figure of Vlad. He and his realm became strange, savage, and mysterious through the circulation of these stories and later through the transformations of these accounts in popular media.

Vlad’s legacy

From the othering of the historical figure and the ongoing mystical aura of Eastern Europe, there was only a short leap to the vampire culture that developed around Vlad in the modern periods. Through Bram Stoker’s famous novel Dracula, first published in 1897, Vlad became associated with a vampire, essentially someone who returns from the dead in the guise of a creature in order to attack the living, who in turn also become vampires.

Sources like the Ambras Portrait, Modrussa’s description, and the German pamphlets, among others, informed Stoker’s research for his novel. Stoker’s Dracula became a monstrous, ruthless figure, mysterious and disturbing to the reader just like the realm from which he hailed. Stoker’s novel was further popularized through numerous creative adaptations in films, plays, comic books, novels, art, and more during the 20th and 21st centuries, contributing to the ongoing fascination with vampires and Eastern Europe in the popular imagination.