Jeremias Schul, Portrait of a Lady Holding an Orange Blossom, mid-18th century, oil on canvas, 80 x 56.2 cm (Art Gallery of Ontario)

In Portrait of a Lady Holding an Orange Blossom, a young woman stands in ¾ profile, gazing directly at the viewer. This orientation offers a flattering silhouette of her elegant dress that highlights the wide silhouette created by the hoops that support her skirts and give emphasis to her femininity. In her right hand, the lady holds an orange blossom and in her left hand, she holds the edge of her decorative apron. The outdoor garden setting includes a potted orange tree and an obelisk or fountain in the distant background. This oil painting, with a semi-legible signature of J. Schul. fec at the lower left and dated to the mid-eighteenth century, was acquired at auction in 2020 by the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Why does her dress matter?

During the eighteenth century, when the transatlantic slave trade was at its peak and many people of color were subjected to forced labour and positions of servitude, dress was a visible signifier of social position. Lady and servant would have been dressed in markedly different ensembles reflecting their class and station. Similar works from this time period typically show women of color in positions of service or wearing dress or head wraps that mark their bodies as “other,” as is evident in Portrait of Madeleine (formerly known as Portrait of a Negress) by Marie-Guillemine Benoist and also in Portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle and her cousin Lady Elizabeth Murray from about 1776.

David Martin (attributed), Portrait of Lady Elizabeth Murray and Dido Elizabeth Belle, in or about 1776, oil on canvas (Perthshire: Scone Palace)

What makes Portrait of a Lady holding an Orange Blossom a rare and remarkable work is the fact that this young woman of color, is fashionably dressed in an expensive gown that signifies elite social status. She holds an orange blossom in her hand, a symbol of purity, innocence and chastity, which may signal that this is a wedding portrait. Portraiture, during this period, was the purview of the elite since it required much time of the sitter and the artist. Although the dress may have been borrowed, her dress offers clues that may be helpful in narrowing the date for the work, since fashion is ever changing and only looks right at a given place and time. Each element of her dress—the color, the textile, the cut and style, and the type of ornamentation—provides clues that can help to date her ensemble based on what was in fashion at a particular time.

What is she wearing?

Jeremias Schul, Portrait of a Lady Holding an Orange Blossom, mid-18th century, oil on canvas, 80 x 56.2 cm (Art Gallery of Ontario)

This young lady is wearing an exquisite pale blue silk gown with a fitted closed-front bodice trimmed with ribbon edged in silver. The low, square neckline of her dress is filled in with a scarf known as a fichu. Her dress has elbow length sleeves decorated with horizontal bands of silk organza and finished with detachable lace cuffs. Her upper torso is erect; her shape formed by the stays (a fully boned bodice worn underneath clothes that supported the bust and that created a smooth conical shape in the torso) worn underneath her dress and chemise. Dresses at this time were often worn with a decorative stomacher (a V-shaped decorative cloth that filled the opening at the bodice) and this lady does not wear one. The bodice of her dress has no visible seams or closures suggesting that it fastens at the back. This style, which could only be donned with the help of a servant, was typically worn by a girl or young lady prior to marriage. Her wide skirt is supported by small paniers (hoops) and accessorized with a decorative apron made of very fine silk gauze. Her hair is not fashionably powdered (like that of Susanna van Colleen in the painting shown below) but is covered by a small lacy white cap edged with silver and trimmed with blue ribbon.

Not only is her silk dress very fine, but its silver-edged trimmings (along the top edge of the bodice and on the sleeves ) and the detachable Chantilly lace engageantes (sleeve ruffles) would have been expensive. Her neck scarf and decorative apron are made of very fine translucent silk gauze, a textile that was not only very costly, but which also tore easily and could not be laundered. She is also wearing a double strand pearl choker necklace, pearl bracelets on each wrist, and very large gemstone earrings. Each element of this elegant ensemble would have been expensive and a signifier of her high social standing.

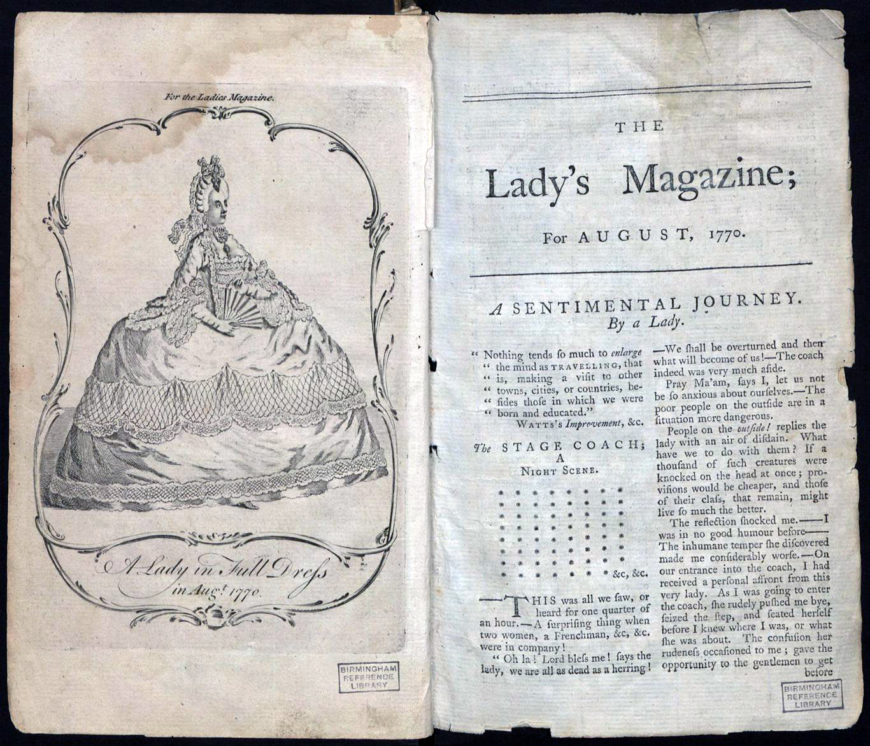

Lady’s Magazine or Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex, Appropriated Solely to Their Use and Amusement, was an early British women’s magazine produced monthly from 1770 until 1847. The magazine here is from

What elements in her dress help date the painting?

Change is inherent in the notion of fashion and during the latter part of the eighteenth century, the rise of fashion journals fueled the desire for novelty. This illustration from The Lady’s Magazine dated to August 1770 shows formal court dress—the ultimate display of wealth and status—which at this time dictated wide skirts supported by panniers, and rigid bodices supported by stays. Over the course of this decade, fashions for women would change with variations in the width of the skirt, shape of the bodice, length of the sleeve, and trimming providing clues that may be helpful in narrowing the date for Schul’s painting.

Anne Frankland Lewis, ‘Dress of the Year’, 1774, watercolor on paper 36.83 x 25.4 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

A watercolor illustration by Anne Frankland Lewis, a British woman who painted her favorite dresses from her wardrobe, presents her “dress of the year” for 1774. Her blue dress features a deep square neckline filled in with a translucent fichu. She is wearing a choker style necklace and both wrists have matching jewelry. She wears a style of dress known as a robe a la française. This style of dress, which was popular throughout Europe, especially from about 1740–80, opened at the front and featured wide skirts supported by hoops. The front bodice was sewn or pinned closed with a decorative stomacher and the back featured wide box pleats falling from the shoulder to the hem. The color of the dress and the length and trimming of the sleeves in the illustration by Frankland Lewis are similar to Schul’s Portrait of a Lady.

Hermanus Numan, Portrait of Susanna van Collen née Mogge and her daughter, 1776, oil on canvas, 80 x 64 cm (Rijksmuseum)

A portrait from the Rijksmuseum dated to 1776 shows Susanna van Colleen wearing a similar robe a la française or sack-back gown in blue, a popular choice during the 1770s. The color of the textile as well as the detail of the sleeves, neckline and cap are very similar to that worn by the sitter in Schul’s Portrait of a Lady.

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Marie Antoinette in a Park, 1780–81,

drawing, black, stumped and white chalk on blue paper, 58.9 x 40.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Towards the end of the 1770s, the styles of dress changed with a style of gown called a polonaise, which allowed the skirt to be looped up with tapes in the skirt, becoming more popular. Sleeves also became longer and tighter. An example of the prevailing fashions of the 1780s, which include the softly rounded silhouette of the robe á la polonaise with a flounced decorative apron and high powdered hair can be seen in a pencil drawing of Marie Antoinette by Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun from The Met.

Woman’s Dress (Robe à la française) England, 1770-75, silk plain weave (faille), moiré finish, with silk passementerie, 165.1 cm high (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Aside from looking at comparable paintings and illustrations, it can also be helpful to identify extant garments in museum collections to help date the clothing in a portrait. A gown in blue silk with a similar length of sleeves and width of skirt is dated to 1770–75 in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

By comparing the details of the dress and hairstyle worn by the young woman in Schul’s Portrait of a Lady to the prevailing fashions of the period, we are able to narrow the probable date of the work to the 1770s. After 1774, high powdered hair was fashionable and in the 1780s, large hats or other hair ornamentation became popular, and this lady’s hair is unpowdered and her cap is small. The young lady’s dress does not feature the extremely wide skirts supported by hoops that is seen in the Lady’s Magazine Illustration of 1770. Pastel blues, pinks, greens and yellows were popular in the 1770s and towards the end of the decade, the styles of dress changed with the softly rounded silhouette of the robe a la polonaise becoming more popular in the 1780s suggesting that the work was painted sometime before this shift in fashionable silhouette. The details of the sleeves are also notable since the sleeves became longer and tighter in the 1780s. A portrait was an expensive proposition and sitters would not want to be represented in an out-of-date style.

While research is still ongoing, the Art Gallery of Ontario has suggested that the work may be by John Christoffel Schultz, a Dutch painter and printmaker who lived from 1749–1812 or possibly his uncle Jeremiah Schultsz (dates unknown). Both worked in Amsterdam.

Jeremias Schul, Portrait of a Lady Holding an Orange Blossom, mid-18th century, oil on canvas, 80 x 56.2 cm (Art Gallery of Ontario)

How can we interpret this painting?

The narratives of history have largely been told from a white, Eurocentric viewpoint. The painting Portrait of a Lady Holding an Orange Blossom in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario challenges that notion in presenting a woman of color in a sumptuous and fashionable gown associated with the European elite. Her posture does not suggest a position of servitude and she gazes directly at the viewer. The work includes symbols associated with marriage, suggesting that this may be a wedding portrait, making it an exceptional work for a time when portraiture was considered a high art. Who she is and how this painting came to be has yet to be unraveled, but a close reading of the dress has provided clues to narrow the window for future research.