View of the nave, Balthasar Neumann, Vierzehnheiligen (Fourteen Holy Helpers) Church (Germany), 1742–1744 (photo: Reinhold Müller, CC BY-SA 4.0) (Google Street View of the interior)

On a bright summer day, when sunlight pours through the windows of Vierzehnheiligen Church at just the right angle, the interior glows with dazzling warmth. Joyful painted and sculpted putti fly overhead, while sculpted foliage and leafy cartouches seem to organically grow over the marble columns and the rippling curvature of the white walls. The architecture appears to dematerialize in this radiant light, and—just for a moment—space, light, and three-dimensional ornament becomes the true substance of this interior. This level of grandeur, spectacle, and rich decoration was not exclusively reserved for Vierzehnheiligen Church, but typifies many of the religious spaces, noble palaces, and theaters built in Germany during the 18th century.

In the 18th century, Germany was not a politically unified country as we know it today. Instead, this region was a collection of territories governed by different ruling families, many of whom were avid patrons of architecture who transformed their principalities into major centers of artistic production.

Map showing German States (center), 1742. L’Allemagne, dressee sur les observations de Tycho-Brahe, de Kepler, de Snellius sur celles de Messieurs de l’Academie Royale des Sciences &c, sur Zeiller et autres auteurs anciens ou modernes. Par G. de l’Isle, Geographe. A Amsterdam, Chez J. Covens et C. Mortier. J. Condet schulpsit (David Rumsey Map Collection)

Hundreds of new buildings dotted the landscape, many with elaborate interiors designed to overwhelm all who stepped inside. Scholars have had difficulty characterizing 18th-century German architecture, viewing it as a superficial (or even exaggerated) imitation of the French Rococo and Italian Baroque styles. However, artists in German-speaking territories transformed Rococo ornament into three-dimensional sculptural forms. They manipulated space and masked architectural structure, and never clearly adopted a single style. Germany’s superior woodworking and stuccowork traditions also aided in refashioning the imported Baroque and Rococo styles.

Balthasar Neumann, Vierzehnheiligen (Fourteen Holy Helpers) Church, 1742–1744 (photo: karaian, CC BY 2.0)

Vierzehnheiligen: light, location, space

Scholars estimate that, between 1700 and 1780, more than 200 architecturally significant churches were erected throughout southern Germany. At this time, many Central European monasteries had the financial resources and sufficient landholdings to commission ambitious structures to communicate the ideas of their faith and accommodate the growing influx of pilgrims. Some churches, like Vierzehnheiligen, had become important pilgrimage sites by the 16th century. Pilgrims journeying to these churches also helped to fund their construction.

Balthasar Neumann, central altar, the Shrine of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, Vierzehnheiligen Church, 1742–1744, Bad Staffelstein, Germany (photo: Aarp65, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In 1735, a Cistercian monastery held a competition to design a larger more magnificent basilica and shrine for Vierzehnheiligen to mark the site where a shepherd had spiritual visions of the “Fourteen Holy Helpers” in the 15th century. The Fourteen Holy Helpers were viewed as healing intercessors who helped with a range of ailments (headaches, fever, and plague to name a few). With the encouragement of indulgences and as news of the Fourteen Holy Helpers spread, thousands of pilgrims flocked to Vierzehnheiligen every year.

Friedrich Karl von Schönborn, the Prince-Bishop of Würzburg and Bamberg, selected Balthasar Neumann’s design and Gottfried Heinrich Krohne supervised. The noble Schönborn family had considerable power in the 17th and 18th centuries, and the Schönborns were enthusiastic patrons (and students) of architecture. While Friedrich Karl von Schönborn was not necessarily the financial backer of the project, without the Prince-Bishops’s involvement in the project, Neumann would not have been selected to design the space.

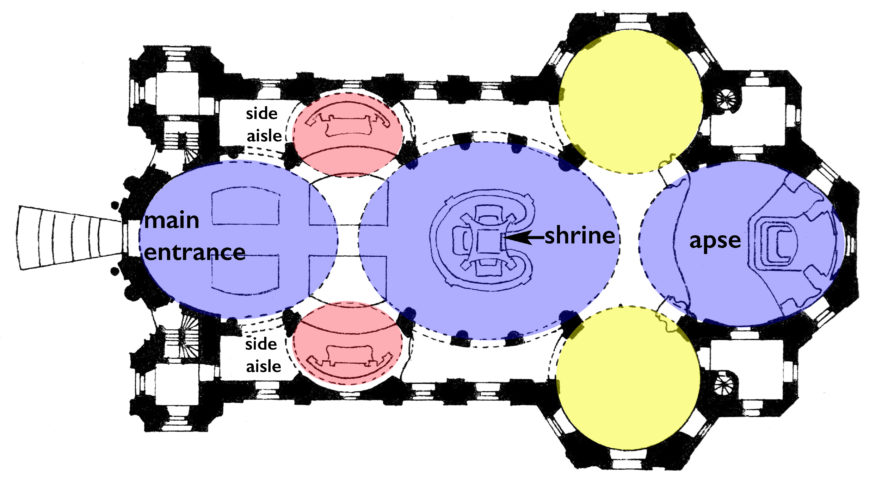

Vierzehnheiligen Plan, from Geschichte der Deutschen Kunst von frühesten Zeiten bis zur Gegenwart von Wilhelm Lübke, Stuttgart, Verlag von Ebner & Seubert (Paul Neff) 1890, p. 794, fig. 624. Here the blue ovals define the nave and the yellow circles define the extent of the transept.

Viewed from the exterior, it appears that Neumann constructed a traditional Latin-cross basilica, however, once inside, the walls seem to ripple and almost disappear. Neumann’s architectural plan is a complex arrangement of five ovals, vaulted ceilings, and large windows. Neumann used a sequence of three longitudinal ovals in the nave (the central aisle of a basilica), with the largest oval centered above the shrine of the Fourteen Holy Helpers. Two domed ovals, on either side of the nave, form a transept (a hall that crosses the nave at a right angle — in the plan above the space with domes indicated in yellow)). Two smaller ovals define the side aisles. The effect, when standing in the nave, is of an undulating arcade.

View in the nave, looking to the entrance, Balthasar Neumann, Vierzehnheiligen Church, 1742–1744 (photo: ErwinMeier, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The nave’s masonry (stone) walls feature large windows, which flood the interior with light. Neumann’s design makes the interior appear more open and airy, like a delicate frame covered in jubilant rocaille forms. The central altar, designed by Johann Jakob Michael Küchel, is a baldachin (ceremonial canopy over an altar) composed of sinuous C- and S- curve shapes, which complement the sculptural nature of Neumann’s interior.

Cosmas Damian and Egid Quirin Asam, Abbey Church of Weltenburg on the Danube (Kloster Weltenburg an der Donau), 1716–1735, Bad Staffelstein, Germany (photo: Mattana, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Staging sacred dramas

The locations of 18th-century German churches can be just as picturesque as the buildings themselves. Vierzehnheiligen overlooks the River Main. The Benedictine abbey church of Weltenburg, designed by the Asam brothers in 1721, is set idyllically on the Danube River. The Asam brothers were not only highly trained architects, but also Cosmas Damian Asam was a talented painter and Egid Quirin Asam specialized in sculpture and stuccowork.

Left: Cosmas Damian and Egid Quirin Asam, main altar with St. George slaying a dragon, framed by Solomonic (spiral) columns, Abbey Church of Weltenburg on the Danube (Kloster Weltenburg an der Donau), 1716–1735, Bad Staffelstein, Germany (photo: Allie_Caulfield, CC BY 2.0); right: detail of Saint George (photo: Mattana, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Unlike Neumann’s Vierzehnheiligen, the Asam brothers used windows sparingly at Weltenburg abbey to heighten the theater of the sacred dramas unfolding at the main altar and in the oval dome. On the high altar, Egid Quirin created a stage set of sorts where Solomonic (twisting) columns frame a sculptural group of Saint George slaying a dragon, as he defends a princess to the side. This sculptural group displays such dramatic movements that it almost appears like a tableaux vivant or “living picture,” in which groups of costumed actors present static, posed scenes. Behind this, concealed windows seem to flood this miraculous scene with heavenly light.

Cosmas Damian and Egid Quirin Asam; View of ceiling (Church Triumphant) at Kloster Weltenburg, 1716-1735 (fresco ca. 1721), Bad Staffelstein, Germany (photo: Allie_Caulfield, CC BY 2.0)

On the ceiling, Cosmas Damian’s illusionistic fresco in the dome represents the Church Triumphant. There are other concealed windows which illuminate the domed ceiling and otherwise dark church. The combined effects of theatrical light, illusionistic paintings, and expressive gestural sculptures blur the boundaries between earthly and heavenly space.

Cosmas Damian and Egid Quirin Asam, main altar with St. George slaying a dragon, framed by Solomonic (spiral) columns, Abbey Church of Weltenburg on the Danube (Kloster Weltenburg an der Donau), 1716–1735, Bad Staffelstein, Germany

The Asam brothers’ stuccowork, painterly approach, and brilliant use of color represent the German Rococo style, but the architectural and spatial illusionism of Weltenburg was likely inspired by their knowledge of Italian Baroque artists like Andrea Pozzo and Giovanni Battista Gaulli. Likewise, their ability to seamlessly unify architecture, painting, and sculpture into one coherent religious spectacle is reminiscent of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s work.

François Cuvilliés (lead designer/court architect), Amalienburg (exterior), 1734–1739; Nymphenburg Park, Munich, Germany (photo: Digital Cat, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Amalienburg: The petite maison of Munich

Amalienburg is a small hunting retreat in Munich, commissioned by Elector Karl Albrecht for his wife. François Cuvilliés was the head architect and designer for Amalienburg; he studied architecture in Paris and was known as one of the most talented designers of Rococo ornament in Germany. At Amalienburg, Cuvilliés introduced the petite maison (“little house”) to southern Germany, which was already a popular architectural type among wealthy French patrons who commissioned these small palaces as luxurious retreats away from the formalities of court society.

François Cuvilliés (lead designer/court architect), Johann Baptist Zimmermann (stuccoist), Johann Joachim Dietrich (woodcarver), and Lauro Bigarello (gilder); Hall of Mirrors (Spiegelsaal) of Amalienburg, 1734–1739; Nymphenburg Park, Munich, Germany (photo: Allie_Caulfield, CC BY 2.0) (Google Street View of the interior)

When compared to the rich complexity and splendor of Amalienburg’s gilded and stuccoed interiors, the exterior of this building is rather understated. Painted pale pink and white, Cuvilliés plays with elements of classical architecture—Ionic pilasters (rectangular attached columns) and a broken pediment (here, the triangular form above a doorway which is interrupted—broken—by an arch)—but in true Rococo fashion, they are pure surface ornamentation without any structural function.

Johann Baptist Zimmermann’s stuccowork inside the Hall of Mirrors at Amalienburg is considered the zenith of Rococo interior ornament and is a highpoint of Amalienburg. Situated at the center of the palace, the Hall of Mirrors is a circular room decorated with pale-blue wood paneling, monumental mirrors and windows, and three-dimensional silver-gilt stuccowork on the walls and ceiling.

Although “mirror-rooms” became a staple feature of palaces after Louis XIV’s Baroque-style hall at Versailles, Amalienburg’s room is a distinctly Rococo creation. The mirrors at Amalienburg amplify the richly ornamented walls and dissolve architectural forms. The combined effect of the mirrors, windows (which provide views of the gardens), and silver-gilt ornament of flora and fauna, create endless reflections of the environment, blurring boundaries between nature and man-made forms. Bringing reflections of the outside in unites the rooms’ inhabitants with nature.

Amphitrite and Diana (detail), François Cuvilliés (lead designer/court architect), Johann Baptist Zimmermann (stuccoist), Johann Joachim Dietrich (woodcarver), and Lauro Bigarello (gilder); Spiegelsaal of Amalienburg, 1734–1739; Nymphenburg Park, Munich, Germany (photo: Marlise Brown)

There are no history paintings on the walls, instead, Amalienburg’s sculpted ornament becomes the primary focus. Since Amalienburg was a hunting lodge—complete with a rooftop stand for shooting pheasants—much of the interior decoration references hunting, abundant harvests, the four seasons, or untamed nature. In the Hall of Mirrors, artists sculpted asymmetrical C-scrolls, natural springs, cartouches, shell-forms, hunting trophies, musical instruments, trees, and uncultivated vines that seem to grow over the framed mirrors. Above the cornice, there are four groups of sculpted forms from ancient Greco-Roman mythology representing Diana, the goddess of the hunt; Amphitrite, a sea goddess; Pomona, the goddess of fruit; and Ceres, the goddess of agriculture.

Georg W. von Knobelsdorff (architect) and Friedrich Christian Glume (sculptor), Sanssouci, 1745–1747; Potsdam, Germany ( (photo: Tobias Nordhausen, CC BY 2.0) (Google Street View of the interior)

Sanssouci palace: a palace retreat fit for a Prussian king

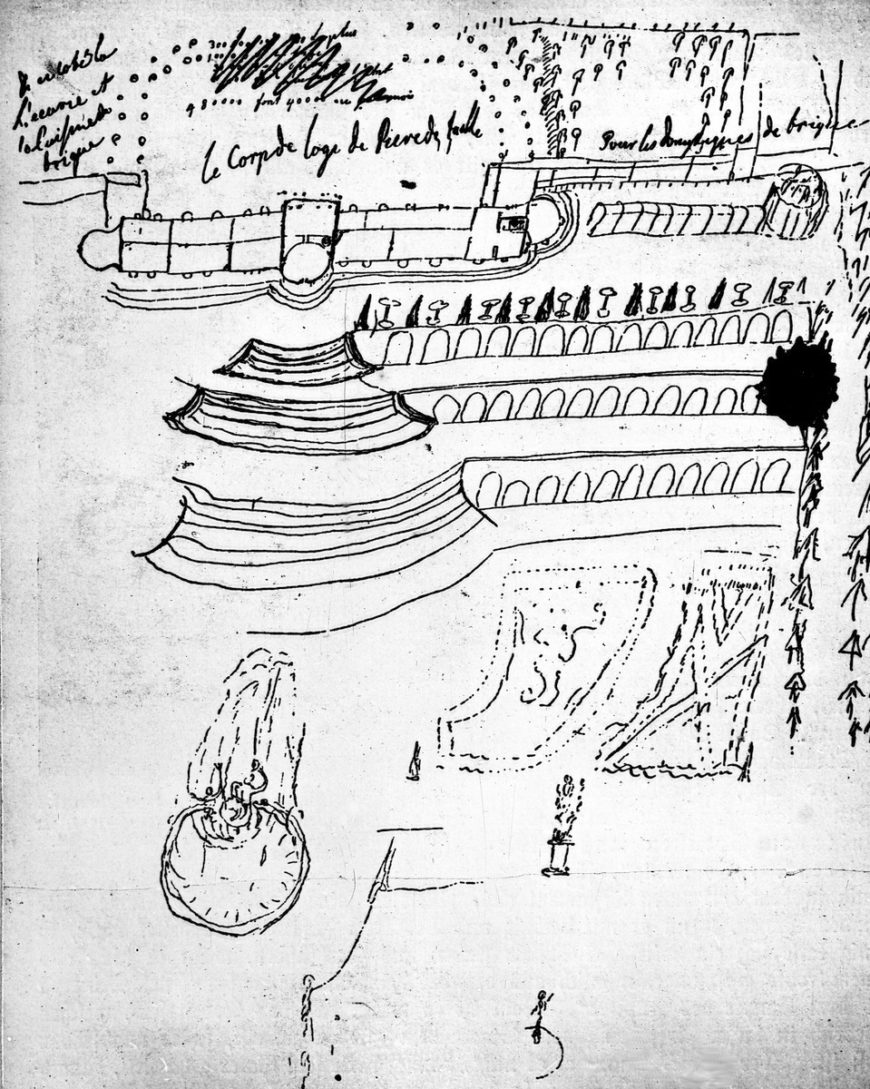

Frederick II, “The Great,” King of Prussia, Sketch of the terrace complex with Sanssouci Palace’s floor plan, 1744, pen, 35 x 18.5 cm, original now lost (Bildarchiv Foto Marburg)

By the second half of the 18th century, Prussia was the most dominant political power in Germany. Frederick “The Great,” King of Prussia, supported a vital period of artistic and architectural activity to commemorate the enlightened absolutism of his reign. Frederick was closely involved in most of his architectural projects, including his vineyard palace, Sanssouci (French for “carefree”), as seen from some of his sketches.

Aerial view of Sanssouci, showing the terraced vineyard (photo: noxoss, CC0 1.0)

Frederick the Great designed the initial concept for Sanssouci palace, its terraced vineyard, and cour d’honneur (the monumental courtyard, partially enclosed by a curved double-colonnade). It was up to his court architect, Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff, and a team of stuccoists, sculptors, painters, and landscape engineers to realize his vision.

Terraces at Sansoucci, Georg W. von Knobelsdorff (architect) and Friedrich Wilhelm Diterich (designer/architect of terraced vineyard), 1745–1747

Like Amalienburg, Sanssouci is a single-story petite maison, however, Frederick’s palace is located on top of a series of six terraces. These terraces, executed by Friedrich Wilhelm Diterich, contains numerous gardens and greenhouses that are designed to grow grapes (for the king’s wine!) and other local and exotic fruits. These terraces curve inward slightly to trap the maximum amount of sunlight.

Caryatids and the name SANS SOUCI. Georg W. von Knobelsdorff (architect) and Friedrich Christian Glume (sculptor), Sanssouci, 1745–1747; Potsdam, Germany (photo: Suse, CC BY-SA 3.0)

On the exterior of the palace, sandstone caryatids of lively male and female followers of Bacchus (the Roman god of wine), support the entablature where the name “SANS SOUCI” is carved. The jovial Bacchic-themed caryatids, sculpted by Friedrich Christian Glume, harmonize with the palace’s vineyards setting and embody the enlightened yet lighthearted environment that the king sought to establish at this palace retreat. However, because Sanssouci Palace was used as Frederick the Great’s official residence in the summer, it was important that the ornament also convey the building’s importance and Frederick’s role as King of Prussia. For this reason, Corinthian columns were used in the cour d’honneur at the main entrance because the richly ornamented column capitals are associated with kings and emperors.

Georg W. von Knobelsdorff (lead designer/court architect), Carl Joseph Sartori and Johann Peter Benkert (stuccoists), Marble Hall, Sanssouci, 1745–1747, Potsdam, Germany (photo: Marlise G. Brown) (Google Street View of the room)

The “Marble Hall,” is the focal point of Sanssouci Palace; it embodies Frederick the Great’s idea of enlightened absolutism through its emphasis on the arts and sciences. Inside the Marble Hall, the oval dome is decorated with gilded stucco ornaments.

Groups of putti and female figures portraying the allegories of architecture, music, painting, sculpture, and astronomy are seated along the cornice. Around the curved walls, there are sixteen Corinthian columns and sixteen Corinthian pilasters; the column capitals are gilded to complement the splendor of the richly ornamented ceiling and the column shafts are a soft white-grey marble.

The columns, walls, and intricate floor of the “Marble Hall” are made of Carrara (from Italy) and Silesian (from Prussia) marble. This is the only application of real marble at Sanssouci (elsewhere, less costly sandstone and faux marble were used). The materials used in the Marble Hall underscore the importance of this space, where King Frederick the Great would host dinners with his elite circle of scholarly friends, including the French writer and philosopher Voltaire, where they could speak freely about literature, politics, philosophy, religion, the arts, and more.

The artworks made during this period, dubbed “Frederican Rococo,” exhibit King Frederick the Great’s predilection for the French painter, Antoine Watteau; however, his architectural commissions convey a sense of stylistic eclecticism, pulling inspiration from architectural sources in Germany, Austria, Italy, England, China, and beyond. For example, the name Sanssouci and the architectural type of the petite maison clearly connect Frederick’s palace to France, but his design also drew inspiration from other Central European palaces and ancient Rome. The lively sculpted caryatids on Sanssouci’s façade are strikingly similar to those found on the Dresden Zwinger (discussed next). The interior of the rotunda-like “Marble Hall” located in the center of Sanssouci was inspired by the ancient Roman Pantheon.

Dragon House, Sanssouci, 1745–1747, Potsdam, Germany (photo: Marek Śliwecki, CC BY-SA 4.0) (Google Street View of the Dragon House)

Hill of Ruins, Sanssouci Palace, Potsdam (photo: Pat M2007, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In addition to the main palace, King Frederick the Great also commissioned several other monuments at Sanssouci Park that clearly showcase his interest in Greco-Roman antiquity (for example the “Hill of Ruins,” seen in the distance from Sanssouci’s main entrance) and chinoiserie-inspired architecture (such as the “Dragon House” and the “Chinese House“). However, many have argued that this type of eclecticism at Sanssouci, coupled with the uniquely constructed terraced vineyard, is distinctly ‘Frederican’.

The Dresden Zwinger and Margravial Opera House: courtly entertainment

The development of permanent spaces for courtly entertainment was an important feature of 18th-century court architecture. The Dresden Zwinger, designed by the architect Matthias Daniel Pöppelmann and sculptor Balthasar Permoser, was initially constructed as a splendid framing element around a large court used to host festivals, tournaments, ballets, and other forms of entertainment.

Guiseppe and Carlo Galli-Bibiena (interior) Joseph Saint-Pierre (exterior), view of stage at Margravial Opera House, 1744–1748, Bayreuth, Germany (photo: Marlise G. Brown)

In the 18th century, several German rulers constructed theaters and opera houses to aesthetically promote their reign. Opera was considered an art form that combined all of the “sister arts” (painting, sculpture, theater, music, and literature) into one coherent spectacle. One of the most important and well-preserved examples of this building type is the Margravial Opera House in Bayreuth.

To commemorate the occasion of their daughter’s wedding in 1748, Margraves Friedrich and Wilhelmine of Brandenburg-Bayreuth (a princess of Prussia and King Frederick the Great’s older sister), commissioned the most celebrated dynasty of theater architects—the Galli-Bibiena family—to design the Margravial Opera House. Royal weddings signified the unification and empowerment of two dynasties, so these events were usually marked by elaborate displays that lasted for days and sometimes weeks. For this particular wedding in Bayreuth, the most important events—like ballets, plays, operas, and banquets—took place at the Margravial Opera House.

Guiseppe and Carlo Galli-Bibiena, view of illusionistic ceiling with scene of Apollo and the Muses at Margravial Opera House, 1744–1748, Bayreuth, Germany (photo: Marlise G. Brown)

The interior of this bell-shaped auditorium is entirely constructed from wood that has been painted or covered in painted canvas. Most of the wooden elements—like the balusters, columns, rails, and so on—were prefabricated and painted off-site and later installed at the opera house. Court artists were usually responsible for constructing temporary festival architecture and decorations for royal weddings; many of these traditional ornaments have been incorporated into the permanent decoration of the theater.

Guiseppe and Carlo Galli-Bibiena (interior) Joseph Saint-Pierre (exterior), view of stage at Margravial Opera House, 1744–1748, Bayreuth, Germany

Theater architects Giuseppe and Carlo Galli-Bibiena used heraldic emblems of the houses of Brandenburg and Hohenzollern to decorate the interior as well as classical love stories from mythology, flower garlands, rocaille forms, cartouches, and a large ceiling painting of Apollo (the god of music) and the Muses (the Greco-Roman goddesses of the arts, literature, and science). Above the two trumpeter’s loges (private boxes in a theater), flanking both sides of the stage, are the Margravial couple’s monograms accompanied by gilded statues representing the allegories of Justice, Generosity, Providentia, and Wisdom—which were qualities that Margravine Wilhelmine and Margrave Friedrich wanted to associate with their reign in Bayreuth.

Although these asymmetrical patterns, untamed foliage, imaginative shellwork, and sinuous designs appeared in France first, Rococo ornament undoubtedly reached its fullest three-dimensional form in Germany. Woodcarvers, stuccoists, gilders, painters, and other artisans transformed the two-dimensional Rococo designs found in French ornamental prints into three-dimensional sculpted forms in German architecture. By working collaboratively to treat each structure as a coherent decorative whole, the splendor and spectacle of 18th-century German architecture continue to delight and intrigue visitors today.

Additional Resources

Prussian Palaces & Gardens in Berlin, Potsdam, and Brandenburg

Sanssouci Palace: Retreat on the Vineyard

Google Arts & Culture: Sanssouci Palace

The Margravial Opera House – a monument of Baroque festival culture

From Geometric to Informal Gardens in the Eighteenth Century

German and Austrian Porcelain in the Eighteenth Century

Gauvin Alexander Bailey, Baroque and Rococo (London: Phaidon, 2012).

Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, Court, Cloister & City: The Art and Culture of Central Europe 1450-1800 (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1995).

Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Rococo Architecture in Southern Germany (London: Phaidon Press, 1968).

Maki Kuwayama and Joachim Käppler, “Vierzehnheiligen,” The Process of Making: Five Parameters to Shape Buildings (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2019).

Jennifer D. Milam, Historical Dictionary of Rococo Art (Blue Ridge Summit: Scarecrow Press, 2011).

Vernon Hyde Minor, Baroque & Rococo: Art & Culture (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1999).

Christian F. Otto, Space into Light: The Churches of Balthasar Neumann (Cambridge: The MIT Press and The Architectural History Foundation, 1979).

Thomas Rainer, Markgräfliches Opernhaus (Munich: München Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung, 2018).

John Summerson, The Architecture of the Eighteenth Century (London: Thames & Hudson, 1986).

Petra Wesch, Rosemarie Heise-Schirdewan, and Bärbel Stranka, Sanssouci. The Summer Residence of Frederick the Great (Munich: Prestel, 2013).

Michael Yonan, “The Uncomfortable Frenchness of the German Rococo,” Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century, no. 12 (2014): pp. 33-51.

Michael Zajonz, Sanssouci. Park, Palaces, Other Structures (Munich: Prestel, 2016).