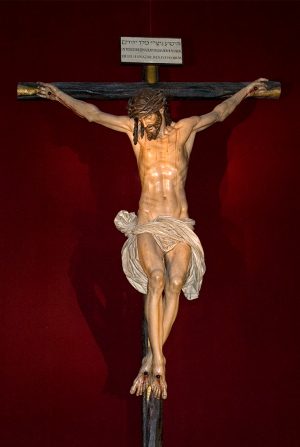

Juan Martínez Montañés and Francisco Pacheco, Christ of Clemency, c. 1603–1605, polychromed wood (Seville Cathedral) (photo: Anual, CC BY 3.0)

“The Lord Christ crucified must be [portrayed] alive, before having expired, with his head inclined to the right side, looking toward whatever person might be praying at his feet, as though Christ himself were speaking to him or her, and as though complaining that what he is suffering is for the sake of the one praying. And so the eyes and face of Christ should have a certain severity, and the eyes should be completely open.”

So says an early seventeenth-century contract stipulating the appearance of a sculpture of Christ on the cross for Seville Cathedral. The crucifix’s patron, Mateo Vázquez de Leca, the archdeacon of Carmona (a position at the Seville Cathedral), went to great length to instruct the artists on how he wanted this sculpture to appear. Today, it is known as the Cristo de la Clemencia, or Christ of Clemency, and it was sculpted by Juan Martínez Montañés and painted by Francisco Pacheco likely between 1603 and 1605.

The God of Wood

Juan Martínez Montañés, Nuestro Padre Jesús de la Pasión, 1618 (Iglesia del Salvador, Seville) (photo: Anual, CC BY 3.0)

Juan Martínez Montañés was a Spanish Baroque sculptor who was sometimes called the “God of Wood,” or “Dios de la Madera,” for his skill working this material. He was known for the subtle naturalism of his sculptures. Sculpting in wood allowed him to create graceful bodies that, unlike the work of some of his Baroque contemporaries, were never flashy or overly distorted. He made many sculptures in Seville, including Jesus of the Passion (Jesús de las Pasión) from 1618. His renown was international, and some of his works were even shipped to the Spanish Americas.

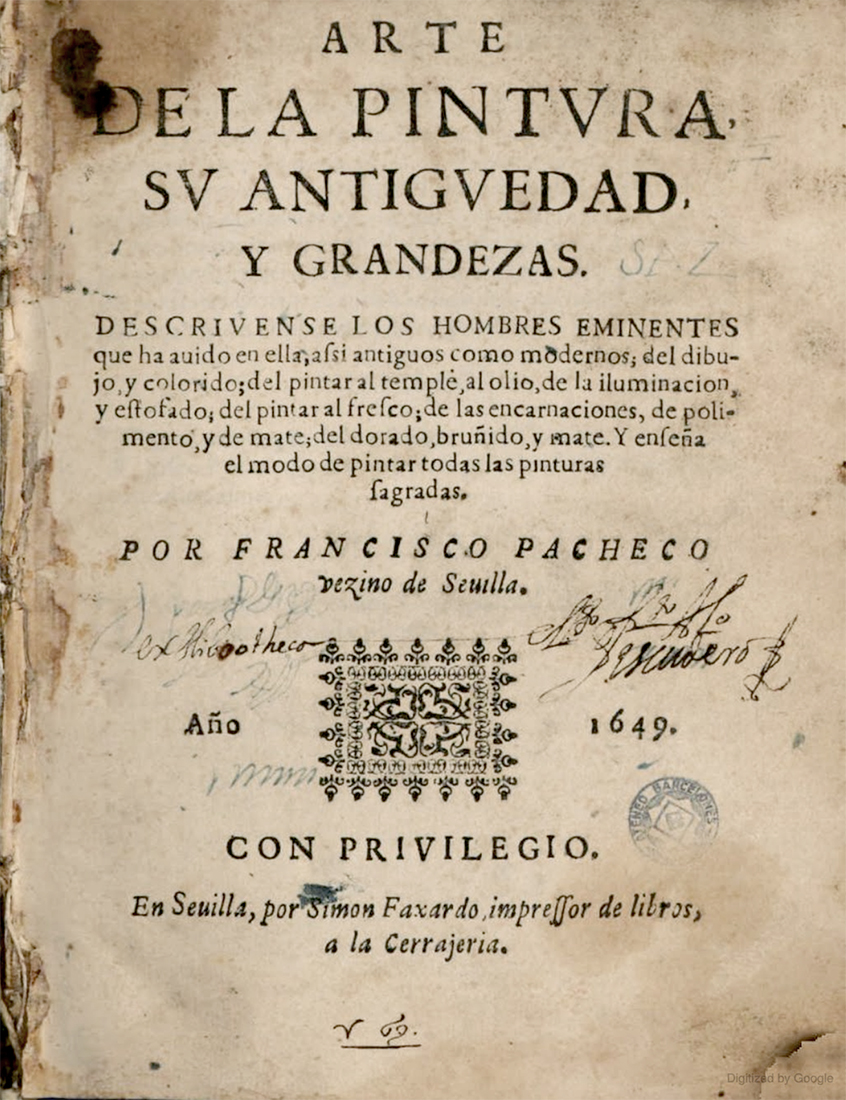

Francisco Pacheco was a painter, but is perhaps more famous today for his artistic treatise, The Art of Painting (Arte de la pintura, written in 1638 and published in 1649). The treatise discusses many topics, among them how to paint a wooden sculpture in order to achieve the greatest sense of naturalism. He desired artworks that followed Christian orthodoxy, and in 1618, he became an Inquisition censor for artworks (someone who evaluated artworks for their adherence to Catholic beliefs).

Juan Martínez Montañés and Francisco Pacheco, Christ of Clemency, c. 1603–1605, polychromed wood (Seville Cathedral) (photo: Anual, CC BY 3.0)

Iconography

The Christ of Clemency depicts the Crucifixion. Christ’s lifelike body displays the artist’s interest in anatomy, with the ribcage pressed up against his stretched skin, arms sagging under his weight, and carefully rendered leg muscles, all of which serve to highlight his humanity. Tiny rivulets of blood run down around Christ’s shoulders from the crown of thorns on his head, and, as stipulated in the archdeacon’s instructions, his head is turned down and to the right, with open eyes. His mouth is also open, as if he might be speaking to the viewer.

The four nails that pin Christ to the cross, one for each hand and foot, were also stipulated in the contract for the sculpture. This particular point addressed a long-standing debate within the church over how many nails—three or four—pierced Christ’s flesh.

Juan Martínez Montañés and Francisco Pacheco, Christ of Clemency (detail), c. 1603–1605, polychromed wood (Seville Cathedral) (photo: Anual, CC BY 3.0)

At the twenty-fifth session of the Council of Trent in 1563, the ecclesiastics in attendance stressed the need for imagery that was free of confusion and would not lead anyone astray. Artists were expected to model their figures on canonical sources, like the Bible. Pacheco composed his treatise in part to provide painters with instructions on the “correct” way to produce their works in accordance with the decrees of the Council of Trent.

Based on their reading of Christian sources, artists like Pacheco decided that including four nails was the proper way to represent the Crucifixion. Even though Pacheco’s treatise dates to after the Christ of Clemency, its discussion of four nails relates to the general cultural climate of Seville at this time. Sculptors such as Martínez Montañés followed the decrees and included four nails. Painters like Pacheco, Diego Velázquez, and Francisco de Zurbarán also depicted the Crucifixion in this way, and they may have looked to sculpture made by Martínez Montañés as a model.

Living Sculpture

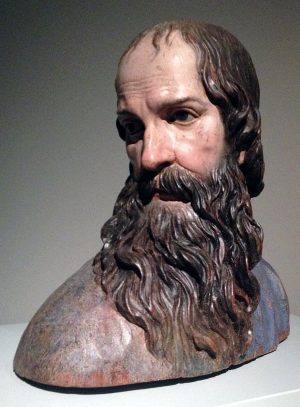

Alonso Cano, Bust of Saint Paul, c. 1660-65, polychrome wood, 47 × 52.5 × 28 cm (Granada Cathedral) (photo: Marsupium, CC 0)

There was a long tradition of polychromed wooden sculptures in Spain. In the seventeenth century, artists such as Alonso Cano and Juan de Mesa became famous for their polychrome sculpure. However, while we may think of a sculpture as the work of an individual, Spanish polychrome sculptures was almost always the result of collaboration among artists who specialized in wood carving and painting. In fact, there were strict rules prohibiting sculptors from painting their own work. After the sculptor modeled and gessoed the figure, a pintor de imaginería (a painter of religious images), would produce the flesh tones and clothing. This was known as the process of “incarnation” (in Spanish, “encarnación”): painting flesh onto the sculpture in order to “bring it alive.”

One motivation for commissioning and creating naturalistic polychromed wooden sculptures was to provoke an emotional or spiritual response in the viewer. Even though polychromed wooden sculpture existed prior to the seventeenth century (and outside Spain), those produced during the Baroque era achieved a new level of naturalism that was considered desirable in the wake of the Council of Trent.

Individuals like Teresa of Ávila and Ignatius of Loyola ushered in a new way of engaging with the divine, one that asked devotees to use their senses to insert themselves into sacred narratives and spaces. Artists like Martínez Montañés and Pacheco responded to the need for artworks that would move viewers emotionally and inspire them to atone for their sins.

Virgin of Macarena (detail), 17th century, polychromed wood (Basilica of Macarena, Cathedral of Seville)

Polychromed sculptures encouraged those who saw them to identify, for example, with the sorrows of the Virgin Mary, whose tears streamed down her grief-stricken face, or with Jesus, whose sorrows and torture were marked onto his body in the form of wounds. To achieve greater realism, sculptors would sometimes add cork, which was then painted, to replicate mutilated flesh and coagulated blood. Other additions, like clothes, wigs, teeth (wooden, ivory, or even real human teeth), leather, and resin added to the impression of living sculpture. Some sculptures even had articulated limbs that allowed them to be placed into different poses, endowing them with even more lifelike qualities. When they were (or are still today) carried through the streets during religious processions, their limbs could move gently, giving the impression of life.

Holy Week Processions

A float in a procession during Holy Week in Seville (photo: Leonardo Moreno, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Sculptures like the Christ of Clemency were often used during Holy Week, a time during which Catholics meditate on the sufferings and martyrdom of Christ.[1] During Holy Week processions, confraternity members would carry floats on which the sculptures would rest, arranged to portray specific moments in the Passion narrative. The floats were also commonly adorned with canopies, textiles, candles, and metal objects, making them quite heavy. Confraternity members would pause frequently to rest and to allow people to gaze at the sculptures. Some confraternity members also engaged in flagellation as they processed, whipping their backs in imitation of Christ, represented before their eyes in wood.

Many of these polychromed wooden sculptures are still used today during Holy Week, and Seville is famous for its elaborate processions. A song from 1927, written by José Muñoz San Roman, captures the experience beautifully:

“the Montañés Christ,

the Virgin of Hope

. . . pass by

on flower-strewn calvaries

beneath fine embroidered canopies

of velvet and precious stones.”