Andrea Mantegna, Camera Picta (Camera degli Sposi), frescos in the ducal palace in Mantua, 1465–74 (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

Working for the man every night and day

The courts of renaissance Italy glittered with splendor. Rulers of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries sought to magnify their glory and sustain their right to rule through liberal spending and magnificent display, and artists played an important role in this performative world.

The statues created by Nanni di Banco and Donatello for the guilds of Florence reflect the interests of their respective patrons. In Florence, which was a republic, powerful and competitive guilds sought to out-do one another for public prestige, using art and architecture as a way to advertise their constituents’ right to political power. Left: Nanni di Banco, Four Crowned Saints, c. 1410–16, marble, figures 6′ high, Orsanmichele, Florence (Italy) (photo: Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0); Right: Donatello, Saint George, c. 1416–17, marble, commissioned by the armorers and sword makers guild for the exterior of Orsanmichele (Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Practicing one’s trade in a renaissance republic like Florence, Venice, or Siena generally required membership in or the approval of the appropriate local guild. Guilds were associations of skilled workers that controlled trade, determined standards of training and workmanship, and limited outside competition. Like modern-day labor unions, guilds held considerable social and political power. Membership was largely obligatory; this held true whether one was a banker or a painter. Urban trade centers were guild-regulated and highly competitive. Working as an artist in a republic meant garnering guild approval, vying for clients, and tempering one’s creations to the collective tastes of the local merchants and bankers who collectively governed the city. The rapid installation of increasingly spectacular sculptures for the guilds of Florence at Orsanmichele is an example of such competition at work.

The situation was different at a renaissance court where power over a region was concentrated in the hands of a single ruler whose individual needs and aesthetic tastes were dominant. Working for a prince—a catch-all term for a sovereign ruler of a territory—put an artist outside the reach of guild constraints while bringing a whole different set of opportunities and challenges.

Visual associations with Roman antiquity and the medieval Chivalric Order are expressed on the classically inspired, two-story marble arch erected at the entrance of the Castel Nuovo in Naples. The magnificent central decorations of this structure depict the triumphal entry of Alfonso V into Naples in 1443. Like a Roman general, he is shown seated in a canopied chariot carrying an imperial orb, while he wears the insignia of the Chivalric Order of the Lily around his neck. The structure was designed by Francesco Laurana and others, 1445–58, Naples, (photo: Berthold Werner, CC BY-SA 3.0)

What was a renaissance court?

Giorgio Vasari, Cosimo I with his Architects, Engineers and Sculptors, 1555–63 fresco, Palazzo Vecchio, Sala di Cosimo I, Florence

In a political sense, a court was the space inhabited by a prince and his (occasionally her) entourage of family, administrators, officials, and and courtiers, including administrators, officials, and ambassadors. The physical court was generally a palace or castle that functioned as the prince’s primary residence as well as the financial and administrative center of government.

In addition to the political and physical realities of a court, there was also the theoretical concept of “the court” as an ideal of civilized life and of intellectual and aesthetic refinement (the remnants of these ideas are felt today in the word “courtesy”). These conceptual associations were carefully fostered by renaissance rulers who sought to justify and celebrate their right to rule through carefully constructed noble identities. The nobility of a person could be communicated in multiple ways including one’s dress and manner of speaking, one’s dancing and dining habits, one’s recreation activities, and one’s spending habits. By patronizing works of art and architecture, sponsoring pageants and tournaments, and hosting sumptuous feasts, a prince could conspicuously declare his virtue.

In this portrait medal of Leonello d’Este, his name and titles are noted above, below, and to either side of him. It notes his new status as the son-in-law of the King of Aragon (GE[nerus] R[egis] Ar[agonum]). Pisanello, Portrait medal of Leonello d’Este, 1444, bronze, made in Ferrara, 9.5 cm in diameter (Victoria & Albert Museum)

Courts across the European continent were closely connected. Marriages helped solidify political alliances and children of rulers were often sent to be raised and educated at foreign courts. The courts of Naples and Ferrara, for example, were closely intertwined throughout the fifteenth century. Both Ercole and Sigismondo d’Este, sons of the ruler of Ferrara, were fostered at the Neapolitan court, while Ercole and his older brother, Leonello d’Este, both married Neapolitan princesses.

Being a court artist

While circumstances differed from court to court, much as one ruler differed from another, the lives of Italian renaissance court artists were consistently dictated by the demands of magnificence: their job was to construct and amplify the ruler’s princely virtue and the glory of his state. If done well, the skillful artist might parlay their visual successes into personal social advancement and financial independence.

Life at court was complicated and full of intrigue. Artists were not aristocrats. With few exceptions, they came from the artisan class. Artisans were tradesmen, probably most similar to what today we might call the lower middle class. These specialized manual laborers—from woolworkers to woodcarvers—were ranked above the peasantry, but had nowhere near the social or economic privilege of wealthy merchants or the nobility. At court, social status was hierarchical and proximity to the prince, whose favor offered security, was jealously sought after.

Artists’ social positions at court were often hard to define—they lacked the inherent privilege of birth, yet often enjoyed intimacy with the rulers whose portraits they painted, palaces they decorated, and pageants they organized. This intimacy enabled a social mobility unavailable to artists working strictly in merchant communities. Court artists might receive noble titles or knighthoods and compensation could be far more than cash payments. In addition to a monthly salary and a regular supply of grain and firewood, Andrea Mantegna, court artist to the Gonzaga family of Mantua for 46 years, received both a knighthood and gifts of land throughout Gonzaga territory. This generous gifting included property in a prestigious quarter of Mantua where the artist built a stately town home.

As a member of the prince’s household, most court artists were given accommodations and clothing allowances as well as a guaranteed salary (at least in theory). As salaried members of the court, artists produced work outside of the normal market and unrestricted by guild regulations. Sometimes an artist’s creations at court might be treated as gifts—gift giving being a standard form of courtly reciprocity—and compensated through favors. The sixteenth-century female painter, Sofonisba Anguissola, for example, never sold a single painting. As a noblewoman—one of the few of her class, male or female, to undertake training as an artist—selling the creations of her own hand would have compromised her elite status. Earning money through the mechanical labor of painting was seen as a low-class pursuit. Instead, her paintings were given away, treated as gifts that served to advertise her skill without sullying her reputation. Sofonisba eventually earned a coveted place as Lady-in-Waiting to the Queen of Spain, to whom she taught painting, her skills rewarded not through money but through prestige.

A generous prince might confer dowries for artists’ daughters, exemptions from taxes, access to court doctors, as well as revenues from estates, and other luxuries. If hired to create for a patron outside the court, traveling expenses were often included. The Marquis of Mantua, Lodovico Gonzaga, promised to send a ship at his own expense to collect the artist Mantenga in 1460 while King Francis I is said to have offered Michelangelo 3,000 ducats to travel to France in 1546.

Raphael’s portrait of Castiglione whose Book of the Courtier defined sprezzatura, effortless nonchalance, as the courtly ideal. Raphael, Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione, probably 1514–15, oil on canvas, 82 x 67 cm (Louvre)

Of course, not all princes were equally generous—the ruling Sforza of Milan, for example, often failed to compensate the artists in their employ. Herein lies the rub: some rulers treated artists very well while others did not. When in the employ of one who rules absolutely, options for challenging ill treatment were few.

While an artist stood to benefit greatly from the social and financial advancements possible in a court setting, they also faced numerous challenges. Artists were subject to the jealousy and social tensions among courtiers vying for advancement within the court hierarchy. Like courtiers, artists interacting closely with their lord would be expected to exhibit sprezzatura, a carefully cultivated semblance of nonchalance in exhibiting courtly manners and comportment.

Court artists might also experience a risky loss of personal freedom in their dependency upon their ruler-patrons. Working for the glory of a ruler meant close association between one’s art and the political ideology of one’s patron. The death or down-fall of a ruler could pose challenges for the court artist who outlived him. A ruler’s many servants were bound to service through vows of loyalty, vows which were negated by death. If a ruler’s successor wanted continuity with the previous regime, courtly appointments might remain intact. Such was the case for the painter Mantegna who served three successive Gonzaga princes, all eager to maintain the stability of their family’s rule.

On the other hand, someone seeking a break with their predecessor might cancel such appointments. Michelangelo’s employment by a series of ruling popes (the head of the Catholic Church who ruled the territories known as the Papal States) is unusual in this regard—the artist’s exceptional fame meant that even political rivals sought his service.

Courtly nobility and the nobility of art

To Giovan Francesco, illustrious Prince of Mantua: I wished to present you with these books on painting, illustrious prince, because I observed that you take the greatest pleasure in these liberal arts. . . .

With these words, the humanist scholar, Leon Battista Alberti, began his dedication of De Pictura (1435), the first European theoretical treatise on the art of painting since the ancient era. Our present-day recognition of art making as an intellectual endeavor may be traced to Alberti’s text and others that came after. By establishing a theoretical foundation for painting similar to that recognized in literature, Alberti proclaimed art-making as a Liberal Art—an art of the mind. Written in classical Latin (though later translated into the more-accessible Italian vernacular) this proclamation was directed at a learned courtly audience. Alberti was not alone. Scholars have noted that renaissance theoretical writings on art as a noble and intellectual pursuit were overwhelmingly produced at courts.

Courtly rhetoric about the nobility of art and artists served the prince first and foremost. A ruler’s financial investment in works of art and architecture celebrating his magnificence was justified by the perceived nobility and dignity of the art he commissioned. Ironically, conspicuous financial investment in material magnificence was one of the ways rulers might present themselves as above the world of commerce. The goal was to manifest an identity as a liberal prince, too noble to busy oneself with the common world of money.

More than “just an artist”

The catch-all term “artist” that we use today to designate those working in creative fields was not in use in the Renaissance. “Artist” as a professional category is a nineteenth-century invention. Nor were there strict distinctions between crafts. A man designated as a painter in one document might be called sculptor in another and most artists specialized in a range of activities. In the workshop of the fifteenth-century master, Andrea del Verrochio, his students learned the arts of fresco painting and panel painting as well as sculpting in both stone and bronze.

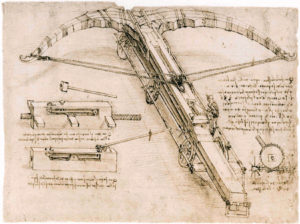

Leonardo da Vinci, Drawing of a giant crossbow design, likely for Ludovico Sforza, late 15th–early 16th century, in the Codex Atlanticus, c. 149a

Accordingly, what we today call artists at court did more than just design buildings, paint paintings and sculpt sculptures. They might be called upon to engineer weapons and fortifications or to construct spectacles for court parties and pageants. Such was the case for Leonardo da Vinci at the court of Milan. His many creations for the duke included a mechanical lion made to entertain the King Francis I of France. Many of the objects produced at court—sometimes only designed by the court artists and executed by others—were ephemeral or perishable: sugar sculptures that could be eaten, gold or silver work that could be melted down, tournament decorations or triumphal entries.

Artists might also fulfill diplomatic functions, traveling to foreign courts as representatives of their lord’s generosity or of shared interests between rulers, such as when Guido Mazzoni left his native Ferrara to work for the Este family’s in-laws, the Aragonese rulers of Naples. Likewise, Guilio Romano, court artist to the Gonzaga of Mantua after Mantegna, received requests for tapestry cartoons from the courts of France, Milan, and Ferrara.

Some artists were content to be creatures of the court, others moved between worlds, finding clientele at court and in merchant-driven cities alike. Leonardo de Vinci spent almost 20 years serving the Sforza of Milan before returning to work in republican Florence when their regime fell, and later finished his career in service to the king of France. Like any job, working as an artist at court had its ups and downs. For many, the rich rewards of court life made it all worthwhile.