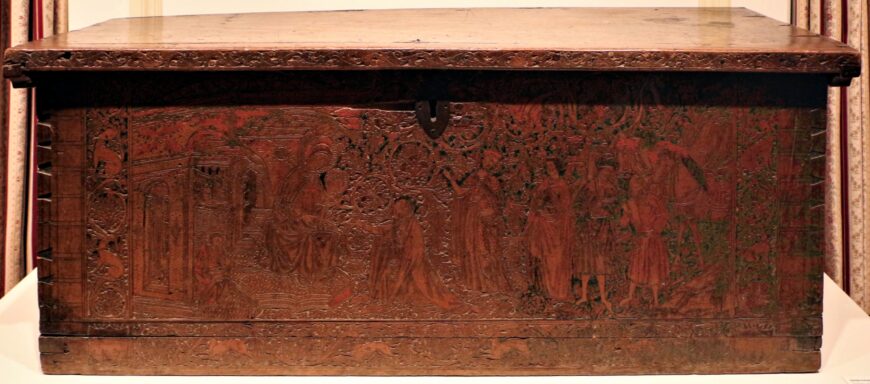

Wooden chest, c. 1450 (likely of Italian origin), carved, stamped, and punched cypress with ink drawing (Putna Monastery, Romania)

Portable objects and cultural connections

Beautiful carved wooden chests like this one made in Italian workshops reached all corners of Europe—including the regions of modern Romania. Putna Monastery (in what is today Romania) preserves one chest that demonstrates the advanced iconographic, technical, and stylistic skills of 15th-century woodcarvers, as well as the portability of such objects and the cultural connections that they reveal across Europe and the Mediterranean.

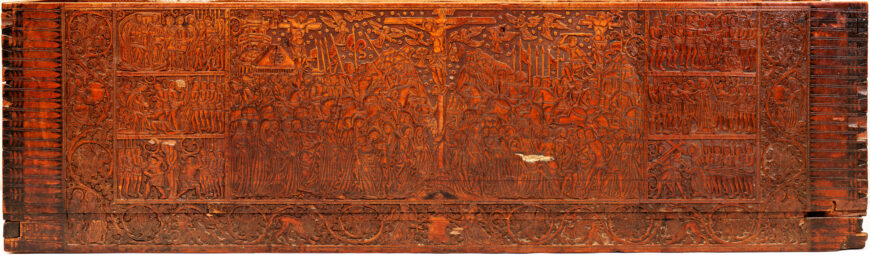

Front panel, wooden chest, c. 1450 (likely of Italian origin), carved, stamped, and punched cypress with ink drawing (Putna Monastery, Romania)

The chest was made of cypress wood in a northern Italian studio. On the front, in the central panel, it displays a main scene of the Crucifixion framed by six smaller panels with vignettes from the Passion of Christ, three on each side. On the edges and along the bottom, the narrative scenes are framed by a decorative band of vegetal and figural motifs, including several shields for coats of arms. The undulating vegetation delineates human and angelic figures, as well as real and fantastical creatures, such as lions and griffins.

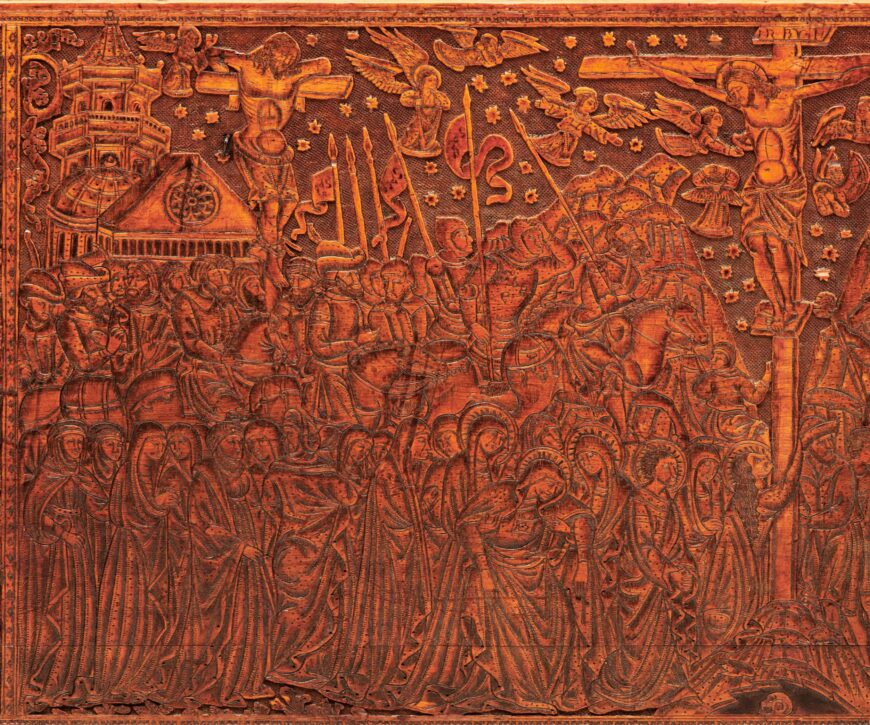

Crucifixion scene, front panel (detail), wooden chest, c. 1450 (likely of Italian origin), carved, stamped, and punched cypress with ink drawing (Putna Monastery, Romania)

The central panel: a Crucifixion scene

The central panel contains a crowded Crucifixion scene focused on the body of Christ on the main cross at the center of the composition. In the lower left, the Virgin Mary falls limp as she mourns the death of her son, Mary Magdalene embraces the foot of Christ’s cross, while a host of other characters look on in amazement at the events unfolding before their eyes. Spears and flags pierce the starry sky and angels descend onto the main stage. On the left, there is a domed church with a distinctive Gothic rose window and an open gallery below, as well as a belfry behind bringing together architecture of the recent past with Biblical events from the ancient period.

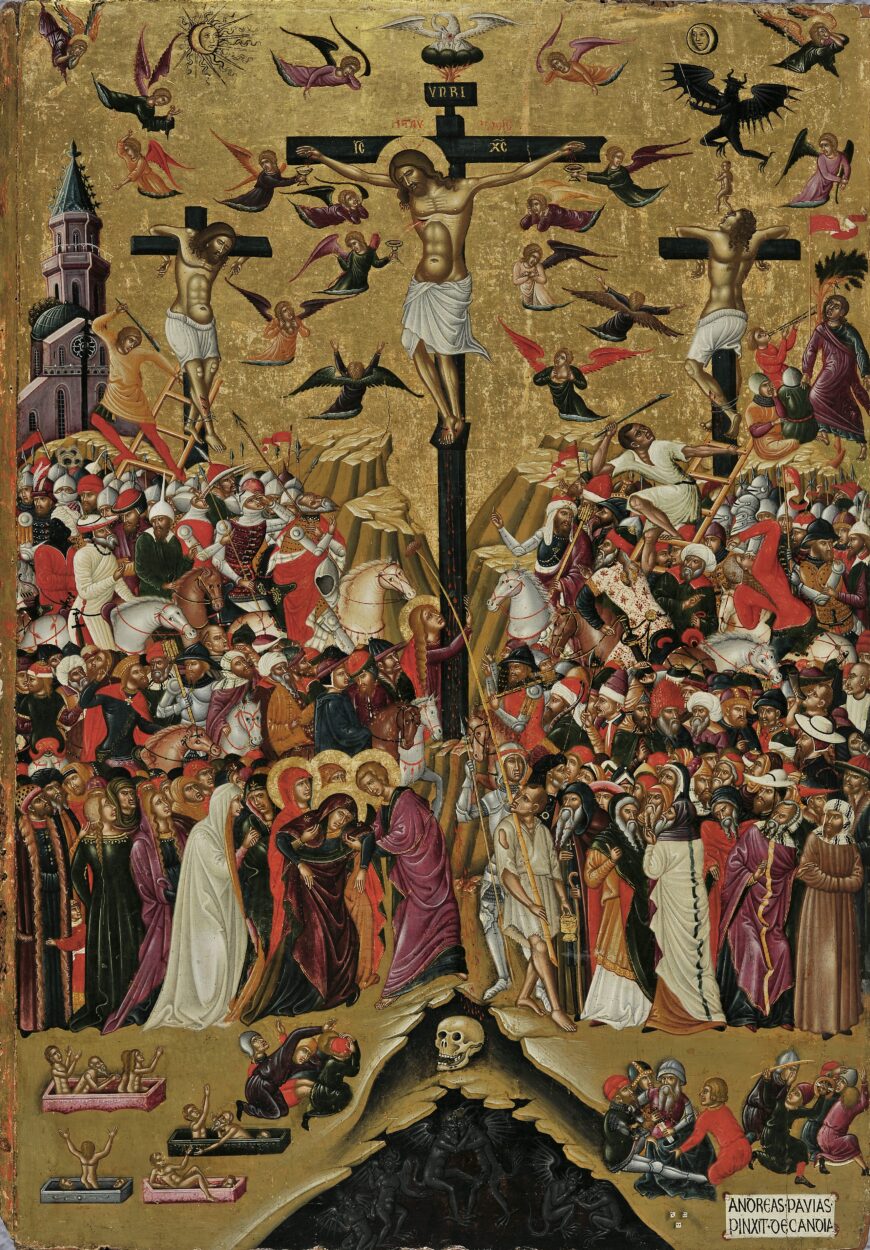

The complex scene on the front of the Putna chest has roots in earlier visual sources, including image types that developed at the crossroads between the Byzantine Empire and western Europe, as is evident in the art of Crete. For example, a 15th-century icon of the Crucifixion executed by Andreas Pavias captures the general characteristics of this type of image, which is also reflected in the decoration of the Putna chest.

Like the chest, the images focus attention on the crowded composition with figures grouped together in the lower half, the three crosses rising to the sky in a mountainous landscape, the angels hovering above, the soldier on the ladder to the right tormenting the crucified thief, and the distinctive Gothic building on left, among other key features. This iconography is rooted in the fresco of the Crucifixion in San Felice chapel, Basilica of San Antonio, Padua, which provides an intriguing precedent for the development of this type of image that circulated in various media in both Italy and Crete in the second half of the 14th century.

Crucifixion panel, wooden chest, second half of 15th century (Northern Italian), carved, stamped and punched cypress with ink drawing (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Based on other surviving examples, it could be concluded that this iconography was quite popular on wooden chests. A panel preserved in The Metropolitan Museum of Art offers a striking comparison. Hailing from a similar northern Italian context of the second half of the 15th century, the panel at The Met likely served as either a lid or front panel for a wooden chest. Although not identical, both scenes are closely related iconographically and stylistically, and use the same technique. Both examples share a composition centered on the three crosses with a legion of figures in the foreground, with a centrally planned church with Gothic elements and a steeple to the left, and angelic figures hovering in the starry sky above.

How was it made and used?

The Putna chest and the Met panel, as well as other similar extant examples, were carved in low relief. They were also stamped and punched on a soft wood, such as cypress, with elements drawn in ink, using a technique called pyrographata, which requires the use of a hot needle to incise the design and accentuate certain details with different colored pigments. Wooden chests decorated in this fashion were produced in Italian (especially Venetian) workshops and exported throughout Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries—including regions of the Balkan Peninsula and the Carpathian Mountains.

Cassone, c. 1450 (Italy), carved, stamped and punched cypress with ink drawing (Indianapolis Museum of Art; photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

These chests were used in both secular and ecclesiastical contexts to store and transport precious objects. An example from the Indianapolis Museum of Art, dated to the mid-15th century, shows a scene with the three wise men from the east, witnesses to the birth of the baby Jesus Christ. The decorative foliated and gashed edge reminds us of earlier examples. The Christian iconography of these chests suggests that they were mainly used in religious and spiritual contexts—perhaps used to store religious objects such as textiles, icons, and manuscripts of spiritual value to the owner.

The similar techniques of execution, appearance, and even iconographical details of these wooden chests suggest that they were produced in workshops that followed common patterns. The central compositions, but especially the framing elements would have been manufactured through patterns, which could then be adapted across media, such as embroidery. Indeed, woodcarvers and embroiderers would have had access to similar preparatory patterns for their creations.

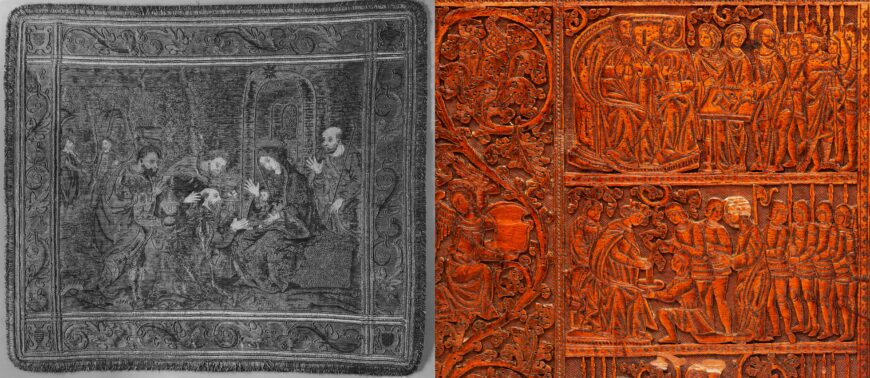

Left: Embroidered textile, The Adoration of the Magi, early 16th century (Italy), silk and metal-wrapped thread on linen (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York); right: front panel (detail), wooden chest, c. 1450 (likely of Italian origin), carved, stamped, and punched cypress with ink drawing (Putna Monastery, Romania)

The forms that appear cross-hatched against the background in the Putna chest, as well as the swirling foliate designs recall visual features of embroideries. The carving method and the pyrographata technique used to create the visual complexity of the carving sit in dialogue with the low-relief effect of embroideries.

A reliquary? A gift?

The Putna chest may have served as a reliquary intended to house the relics of Saint John the New, one of the protectors and patron saints of Moldavia. Another possibility is that the chest arrived in the region from Italy full of textiles and other valuable objects as a court gift. It is known, for example, that Stephen III (who ruled Moldavia from 1457 to 1504) fostered ongoing relations with Italy during his lengthy reign. It is also possible that the chest was used to transport religious objects, such as fabrics, icons, and manuscripts, and possibly reached Moldavia via Serbia and Wallachia (a historical region in the south of modern Romania).

The wooden chest now in the collection of Putna Monastery in Romania certainly originated in an Italian cultural context, and while it originally may have had a private owner, it changed hands and functions over time. Today, it is a museum piece, appreciated mainly for its technical, stylistic, and aesthetic qualities. Nevertheless, this wooden chest is part of a wider network of artistic production that stretches from Italy and Crete to Eastern Europe, demonstrating aspects of the dynamic networks of cultural and artistic relations in the late medieval and early modern periods that extended across Europe and the Mediterranean.