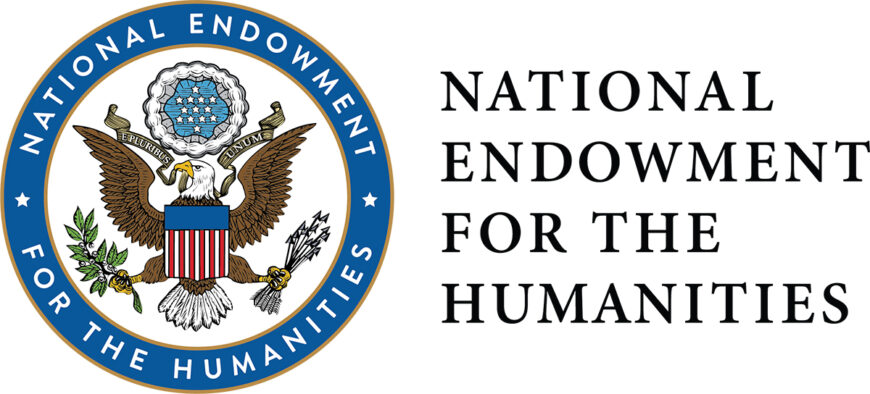

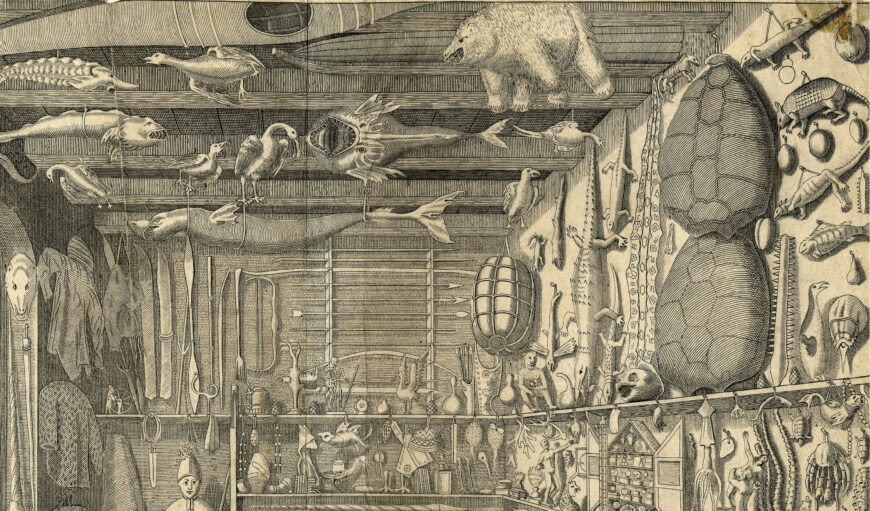

Frontispiece, Olaus Worm, Museum Wormianum (Leiden: Isaac Elzevier, 1655), engraved by G. Wingendorp, 1655, engraving on paper, 27.8 x 35.8 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Hanging from the left-hand side of the ceiling is an upside-down kayak. Off to its right is a polar bear cub. Behind it are stuffed birds and fish. The walls and the floor are similarly crowded with wonders. Animal horns and antlers hang on the left between two windows. Nearby stools appear to be partly made of bone. A narwhal skull perches by the window, its long tusk pointing skyward. On the tiled floor next to it is an enormous vertebra which, next to the stools, might prompt viewers to wonder whether anyone sat on this, too.

This print depicts a room that teems with what today’s viewers might identify as both natural specimens and human-made artifacts. The shelf on the top right displays giant turtle shells, reptiles, an armadillo, and various animal skins. The upper half of the rear wall is devoted to tools for surviving and harnessing nature: bows and arrows, skis, a two-bladed oar (for the kayak hanging above it, perhaps), and items of winter clothing.

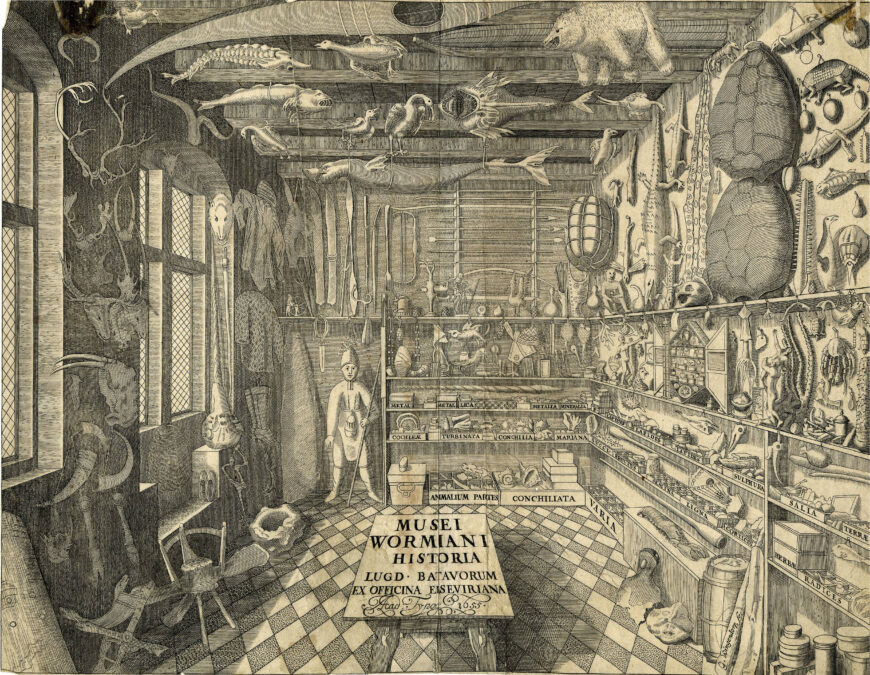

The rear wall with handicrafts, minerals, seeds, and more (detail), Frontispiece, Olaus Worm, Museum Wormianum (Leiden: Isaac Elzevier, 1655), engraved by G. Wingendorp, 1655, engraving on paper, 27.8 x 35.8 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

The lower half of the rear wall combines handicrafts with labeled containers. These shelves continue along the lower right-hand wall, and preserve natural samples. The middle shelves hold compartmentalized boxes devoted to, among other things, metals (metalla), minerals (mineralia), stones (lapides), fruit (fructa), seeds (semina), wood (ligna), barks (cortices), grasses/herbs (herbae), and roots (radices). By putting things made by people in conversation with the bounty of nature, the scene provided viewers with what we might call a visual encyclopedia of the world. [1]

A curiosity cabinet

This print depicts a very particular kind of room: a 17th-century curiosity cabinet. Curiosity cabinets were a type of early museum in Europe. A cabinet was a room containing items from around the world, collected for the enjoyment, education, and scholarly activities of those who could afford to acquire and house them—monarchs, aristocrats, a few wealthy and educated individuals—and their guests. [2]

This example belonged to Ole “Olaus” Worm who was a physician, professor of Latin and Greek at the University of Copenhagen (Denmark), and antiquarian. A modern reconstruction using surviving objects known to have been in Worm’s collection revealed that the print appears to be a faithful representation of Worm’s curiosity cabinet. [3] Unlike today’s typical museums, Worm’s cabinet brought into close proximity objects fashioned by people and what we might today call natural things: stuffed birds, animals, marine life, minerals, and shells.

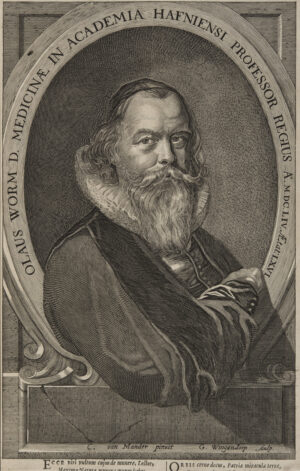

Portrait of Olaus Worm in Olaus Worm, Museum Wormianum (Leiden: Isaac Elzevier, 1655) (Lund University Library)

Worm, a professor and collector

Olaus Worm used his cabinet in his university teaching duties. As a professor of medicine, he practiced anatomy, the study of the body through activities that included opening up cadavers, a practice known as dissection. His work on anatomy was enhanced by his bone collection. As an antiquarian, Worm was also interested in the sorts of objects that people had been making, for millennia, out of natural substances and materials like wood and stone. [4]

Worm’s cabinet contained several artifact types that were sought after by collectors and that appeared regularly in 16th- and 17th-century cabinet catalogs and inventories. This print illustrates a number of such items: crocodile or alligator skins, giant turtle shells, and a kayak. Worm possessed two specimens associated with a creature of myth, the unicorn: a narwhal skull with tusk (standing vertically on the left) and a standalone tusk (hanging horizontally across the middle of the back wall).

Cabinets enabled collectors to organize the world into classificatory systems of their own design. In this print of Worm’s cabinet, the objects hanging from the ceiling include what we might today classify in four different categories: fish, bird, mammal, and human-made artifacts. But what brings these hanging examples together is that they all had a relationship with water: aquatic birds that lived by the ocean, a polar bear cub, the kayak, and (of course) fish.

Efficient use of limited space, with crocodiles, turtle shells, a penguin, and longer items hung on the walls (detail), Frontispiece, Olaus Worm, Museum Wormianum (Leiden: Isaac Elzevier, 1655), engraved by G. Wingendorp, 1655, engraving on paper, 27.8 x 35.8 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

To be sure, practicalities also influenced the display, especially of larger items. On the tiers of shelves along the back and right-hand walls, long things are displayed together, lined up in parallel in order to make efficient use of a limited amount of space. Cabinets often hung crocodiles and alligators from the ceiling for the same reason, although Worm has taken another approach here, lining up his reptilians along the right-hand wall. For the heaviest of items, like whale bones, leaving them on the floor was often the least worst option. It took luck and skill to preserve and transport, over long distances, fleshy body parts. One solution was to display an animal using only its more durable parts—like the bill of a saw shark lined up between the giant turtle shells and the penguin (along the upper right-hand wall), or to display a snakeskin rather than a whole snake. As for creatures like turtles, they were such good eating that it was easier to procure a shell than to get your hands on a whole, preserved example.

At the end of the second shelf along the right-hand wall are objects that only seem to go together in the category of “wavy things:” a squid, complete with tentacles; a crab hanging from a hook with its legs and pincers dangling; a statuette of a man trampling another underfoot while carrying off a woman who waves an arm in distress, a scene that Worm identified as the Abduction of the Sabine Women. This was also the subject of an influential, monumental 16th-century sculpture by Giambologna. This category breaks down the boundary between natural and artificial. By juxtaposing things made by people with natural things, collectors effectively compared the works of humanity with divine creations, and opened up that possibility for visitors to their collections.

Cataloging a collection

Before his appointment as a professor in 1613, Worm had spent years touring around Europe: viewing curiosity cabinets in cities from Basel to Naples, conversing with scholars, and collecting. Like many European intellectuals of his day, he sustained personal connections made on his travels via extensive letter-writing. Worm’s network of friends, students, and correspondents sent him gifts on their own travels, and from their homelands: tortoises, stones with medicinal properties, an Icelandic whale’s tooth chess set. [5]

In 1642 and 1645, Worm published and circulated two short pamphlet inventories of his cabinet. [6] His nephew Thomas Bartholin gave a copy to fellow collector Johannes de Laet in Leiden (in the present-day Netherlands). De Laet used it to identify what Worm lacked, and assembled a care package of specimens for Bartholin to hand-deliver to Worm in Copenhagen. [7]

Title page, Olaus Worm, Museum Wormianum (Leiden: Isaac Elzevier, 1655) (Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C.)

During the last two decades of his life, Worm compiled a four-hundred-page catalog of his cabinet. Published in 1655, the catalog contains this print showing the display of Worm’s collection in his own home at the end of his life. The catalog title, “Account of rare things, both natural and artificial, both domestic and exotic…”, characterizes all of these specimens as rare. [8] In the 17th century, scholars like the English collector and naturalist John Tradescant called the contents of such collections “rarities.” Many artifacts were rare and prized since great distance and effort separated them from Europe.

The far north was as much a region of curiosity for European collectors as Africa, Asia, the Americas, and the Pacific. The trail leading from a polar bear gamboling in the Arctic to a collector in Europe gazing in satisfaction at a newly acquired stuffed animal involved one or more hunters and taxidermists to kill and preserve the animal, and one or more traders through whose hands the creature would pass on its way to a curiosity cabinet.

Worm’s catalog contained a list of authors whose works he had consulted. There were early modern authorities like the Jesuit José Acosta, who spent time in the Americas, the physician Nicolás Monardes, who wrote about “New World” medicaments he had learned about by talking to sailors in Seville (Spain), and the Swedish scholar Olaus Magnus who wrote extensively about Scandinavia. The list of authorities also included much earlier authors, like the ancient Roman poet Ovid.

The catalog comprises four books, broadly organized into minerals and metals; plants; animals; and “artificialia,” or human-made artifacts. Not everything had an obvious classificatory option, however. One of the boxes on the floor of the print is labeled “varia,” or miscellaneous, a term that also appears in the catalog as the final subsection for human-made artifacts.

Book I

The untitled Book I covers natural resources from, by and large, non-living things. Yet it also includes items that do not entirely fit the definition of earth, mineral, or metal. In the subsection on “bitumen”—a sticky petroleum substance—Worm included mumia, or preserved mummy, a medicinal ingredient made of grinding up mummified human bodies. The bodies themselves were preserved using substances like bitumen.

Also included in Book I are amber (a fossilized resin from pine trees) and spermaceti (a waxy substance found in the heads of sperm whales). What links these “products,” for lack of a better word, of human, animal, and vegetable with the mineral section in which they appear is their physical appearance. Powdered mummies and lumps of amber and spermaceti look more like metals and minerals—things mined from the earth—than they do anything that was once alive.

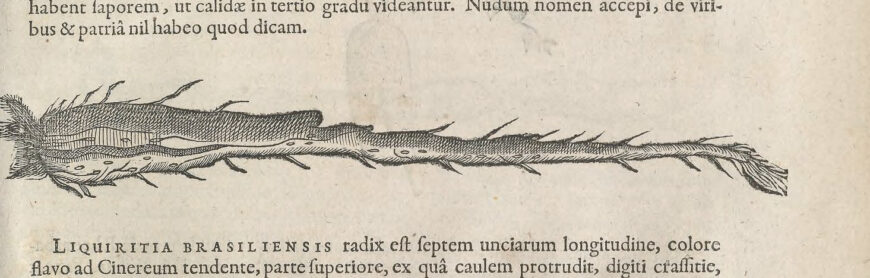

Root illustration from Book II on rare plants and other vegetable material (detail), Olaus Worm, Museum Wormianum (Leiden: Isaac Elzevier, 1655), p. 155 (Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C.)

Book II

Book II is dedicated to rare plants and other vegetable material. These include various roots, woods, and fungi, and plants from distant places, like rhubarb from various parts of Asia, and sarsaparilla from the Americas. Studying plants and animals from distant places was crucial to understanding nature. By examining and handling samples and specimens in his cabinet, Worm classified the world around him.

Lower jawbone of a horse fused with the trunk of an oak tree in Book III (detail), Olaus Worm, Museum Wormianum (Leiden: Isaac Elzevier, 1655), p. 342 (Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C.)

Book III

Book III reveals that Worm’s cabinet contained partial and complete animal skeletons. The book’s sections are anatomical: kinds of feet; animals with blood. It ends with an unusual artifact that melded together animal and vegetable kingdoms, and which appears at the center of the top shelf on the back wall of the print: the lower jawbone of a horse, so deeply fused with the trunk of an oak tree that it was impossible to tell where bone ended and oak began. Worm surmised that the jawbone had been placed on a branch which, as it thickened and grew above and below the bone, fused around it. This unusual object was highly desirable because it challenged understandings of the relationships between categories. By studying category-bending exceptions, naturalists refined their understanding of nature.

Book IV

Book IV covers human-made artifacts in chapters arranged according to material, such as stone and metal. For Worm, even “artificial” objects were thus undergirded by nature’s handiwork: by their underlying substances. Implicitly, God and nature came first; humanity’s ingenious inventions merely extended their work. Humanity has a representative on the print in the form of an automaton standing against the back wall. Operating a wheel made the figure move its limbs, move around, and pick things up. The figure’s spear and costume suggest that it was meant to represent an Indigenous person from a cooler climate. [9]

Book IV contains human-made artifacts from around the world. The wooden artifacts section juxtaposes materials from such regions as Denmark, Greenland, Brazil, and Persia. Visitors could compare cultures and civilizations through the ways they shaped the animal, mineral, and vegetable elements of nature. Yet the boundary between artificial and natural was not absolute. Societies shaped plants and animals through agriculture and husbandry, making, for example, the bones of a domesticated animal like a horse something that was not simply the work of nature.

Circulating the cabinet catalog and print

Worm commissioned the Elzevier family printing house in Leiden, Holland to publish his catalog. He supplied the Elzeviers with a handwritten copy of the book. In 1654, he sent them his own drawing of his cabinet, the design for the iconic print. Worm died just months later. His son Willum Worm, a recent Leiden University graduate, oversaw the catalog’s publication in 1655. [10]

In his preface to the reader, Olaus Worm declared that his goals in assembling and cataloging his cabinet had been to enable anyone curious about nature to examine and read about its wonders. That said, since the catalog was published in Latin, it made knowledge accessible only to people who had already received a relatively extensive education.

Worm’s cabinet is one of a number of 16th- and 17th-century collections documented in printed, illustrated catalogs. Collectors wrote or commissioned catalogs to publicize their collections to their peers, who frequently purchased these catalogs. By consulting catalogs, collectors learned about items they did not have, and could try to obtain specimens themselves. Worm’s cabinet was renowned in his day, and received scholarly, aristocratic, and royal visitors from around Europe. After his death, the collection became part of the cabinet of Frederik III, King of Denmark. By collecting and displaying things that were difficult and consequently expensive to acquire, and recording their collections in print, collectors strove to showcase not just their artistic taste and their expansive understanding of the world but also their wealth and personal connections.