Piedad (in Italian: Pietà — the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus)

Butterflies flutter beside a lion that sleeps peacefully. Flowers and other greenery spring from the reddish-brown earth, all painted with naturalistic precision. In the center foreground, the Virgin Mary mourns her dead son, holding him. Jesus’ broken body arcs across her lap, blood streaming from his wounds. On the left side, St. Jerome, dressed in red and white, kneels while paging through a book. At his feet we see a lion — a reference to the legend that St. Jerome tamed a lion in the wilderness by healing its paw.

Bartolomé Bermejo, Piedad with Canon Lluís Desplà (detail), 1490, tempera on wood (Barcelona Cathedral)

Bartolomé Bermejo, Piedad with Canon Lluís Desplà (detail), 1490, tempera on wood (Barcelona Cathedral)

To the right is the Canon Desplà, who lived in Barcelona, Spain during the fifteenth century, dressed in heavy black robes.

The landscape

While our attention is focused on the figures in the foreground who take up half of the composition, behind them is a vast and detailed landscape. It is filled with cities, windmills, mountains, rocky crags, pathways, waterfalls, rivers, and weather phenomena in the sky.

The artist, Bartolomé Bermejo, renders the landscape with exquisite details and a lush color palette, inviting viewers to delight in his naturalistic effects. It is clear that the artist has studied plants, animals, and insects, as he attempts to capture them faithfully. He uses the relatively new medium of oil paint to build up details and textures.

Jerusalem (detail), Bartolomé Bermejo, Piedad with Canon Lluís Desplà, 1490, tempera on wood (Barcelona Cathedral)

Bermejo’s careful observation of the natural world is paired with his imaginative depiction of Jerusalem in the background where the ancient city looks more like fifteenth-century Europe with its Gothic architecture (note the tall spires, delicate tracery, and rose windows) than an eastern Mediterranean city. Some buildings though, do have small domes, likely the artist’s attempt to reference Jerusalem’s famous domed spaces (such as the Dome of the Rock and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre).

Pairing convincing naturalism with creative invention made Bermejo one of the most original artists of his day. Piedad with Canon Lluís Desplà is Bermejo’s last known completed work before he mysteriously stopped producing art.

The auburn artist on the move

Bartolomé de Cárdenas, often called el Bermejo (which means “auburn” in Spanish), was likely born in the city of Córdoba on the Iberian peninsula around 1440. For much of his career he painted within the Kingdom of Aragón. We have artworks from cities like Valencia, Daroca, Zaragoza, and Barcelona, as well as some textual records that describe aspects of his time in these places. Unfortunately, many details of Bermejo’s life are currently unknown to us.

Bermejo is an example of an itinerant artist — someone who moved around a great deal during his lifetime. He never stayed anywhere for more than ten years. He had a reputation for not completing his work, and was even excommunicated at one point while in Daroca. It is likely that Bermejo was a converso, someone who converted from Judaism to Christianity. While in Daroca, Bermejo married a conversa named Gracia de Palaciano. At this time in Spain, many conversos were suspected of still practicing Judaism. At one point Gracia was called before the Inquisition for not knowing the Nicene Creed (a statement of belief widely used in Christian liturgy). Bermejo’s itinerancy might partially be explained by his being a converso.

Throughout his journeys, Bermejo absorbed and adapted different artistic strategies, including Flemish (Northern Renaissance) ones. It has been suggested that between the 1450s and 1460s, he may have apprenticed in Flanders, today primarily Belgium and the Netherlands, but we have no specific evidence that Bermejo ever traveled there as some other artists of his time did. It is more likely that he was coming into contact with Flemish art through Flemish artists who moved to the Iberian peninsula (Spain and Portugal), and Spanish artists who themselves had also absorbed Flemish artistic ideas. Valencia was well-known as an international and cosmopolitan city, complete with artists from northern Europe as well as merchants selling artworks acquired from there.

Naturalism and observation

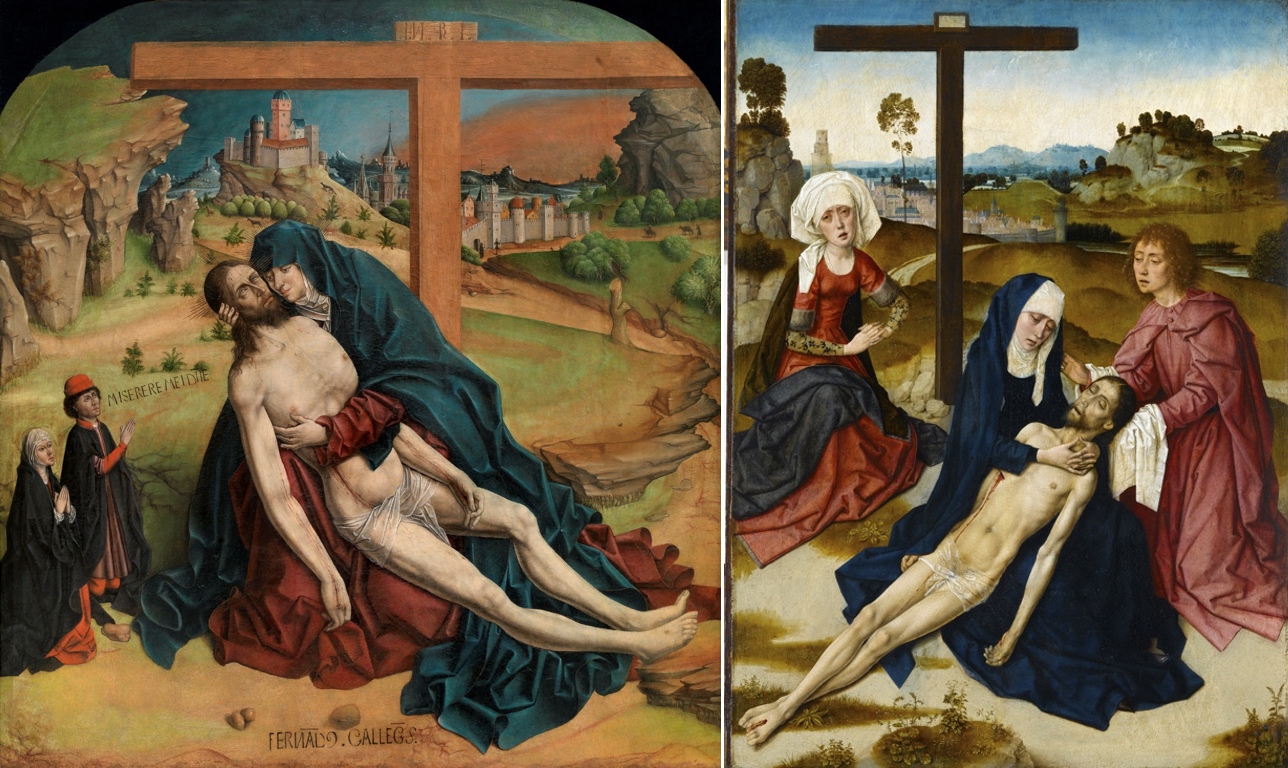

Earlier fifteenth century depictions of the Piedad, such as Fernando Gallego’s painting of this subject, reveal a similar interest in panoramic landscapes, and are similarly influenced by Flemish painting.

Scenes of the Pietà or Lamentation by Dieric Bouts and Petrus Christus reveal that Spanish artists like Gallego and Bermejo adapted elements from these Netherlandish painters. However, few artists (Flemish or Spanish) display the same keen observational interest in botanical elements or fauna as Bermejo does.

Fernando Gallego, Piedad, 1465–70, mixed method, 118 x 111 cm (Prado Museum); right: Dieric Bouts, Lamentation, c. 1460, oil on oak panel, 69 x 49 cm (Louvre Museum)

Mary’s mantle (detail), Bartolomé Bermejo, Piedad with Canon Lluís Desplà, 1490, tempera on wood (Barcelona Cathedral)

If we take a close look at the Virgin Mary’s blue mantle for example, we can see Bermejo’s extraordinary technical skills. The edge of the mantle is decorated with complex golden patterns, and he reveals the green lining as a way to portray the different angles and textures of the textile.

The artist also shows more naturalistic folds in the mantle than the more stylized, angular drapery characteristic of Flemish and Spanish painting of the time (this is especially evident in Gallego’s Piedad). The oil glazing that Bermejo uses also permits him to pay close attention to details. There are more than forty types of plants in the painting, providing viewers with great botanical variety.

More than meets the eye

While Bermejo’s observational skills are on full display in this painting, many of the animals and plants also have deeper symbolic meaning. Small red and white blossoms dot the landscape, symbolizing purity (white) and passion (red). White and orange butterflies flutter around the composition, likely symbolizing resurrection. On the right side of the painting are several European goldfinches (symbols of the Passion and Resurrection). A snake slithers away between the rocks, and a mouse flees into the grass. Both are associated with Satan or evil, and the idea here is that evil is being driven away.

A pile of exposed bones rests behind Mary and her son. It is common to see a human skull and crossbones at the base of the cross in images of the Crucifixion, Lamentation, and Pietà. The bones are Adam’s, and it locates the Crucifixion at Golgotha (Calvary), the “place of the skull,” in Jerusalem. Bermejo also uses them to signal his skill, by depicting more bones than we might normally observe in a such a scene, but also including more difficult bones to paint, such as vertebrae.

Sky (detail), Bartolomé Bermejo, Piedad with Canon Lluís Desplà, 1490, tempera on wood (Barcelona Cathedral)

Different types of weather phenomena take place across the sky, with Bermejo creating various atmospheric effects. On the left, we see thick cumulus clouds and rain pouring down. A blackened sky fills the top portion of the sky, partially obscuring the moon. Closer to the earth in the center of the landscape the clouds begin to clear, and birds fly in straight formation off to the right side of the sky. The rightmost section of the sky is red and golden, and the sun is likely further off to the right. The storms and dark threatening sky refers to the passage in the Gospels about the darkness following Jesus’ death and a possible eclipse. Where the sun should be in the composition, if it were paired with the moon, is the top most portion of the cross. Bermejo may be substituting the top of the cross for the sun to convey the idea that Jesus is the light of the world (the lux mundi), and his death and resurrection allow for entry into the heavenly Jerusalem.

Halo (detail), Bartolomé Bermejo, Piedad with Canon Lluís Desplà, 1490, tempera on wood (Barcelona Cathedral)

Haloes

Jesus, Mary, and Jerome’s haloes look more like golden metal crowns or additions that we see on late medieval and renaissance Spanish sculpture. They differ from painted haloes that we tend to think of in the late fifteenth century in other areas of Europe, often golden disks surrounding the head. Earlier Spanish artists, like Gallego, similarly include the halo as rays of light.

Canon Desplà and Renaissance Humanism

The Piedad described here was completed in 1490 for a chapel belonging to Canon Lluís Desplà i d’Oms in Barcelona Cathedral. Canon Desplà was an archdeacon, and a learned classical humanist. He had Bermejo include his portrait in the painting likely to both advertise his position and demonstrate his piety and contrition as he kneels forever next to Mary and Jesus. The portrait displays great realism. It shows Desplà in three-quarter profile, bearded and with a contemporary haircut. He wears clothes of his time. Bermejo does not idealize his patron, instead painting the canon with sagging skin under his eyes, and other imperfections around the mouth.

While Bermejo’s depiction of St. Jerome is not a portrait, it has portrait-like qualities. Jerome pages through an open book, the written words legible to the viewer, seeming to read about the Piedad as it occurs before him. Bermejo likely included the scholarly Jerome, with his accompanying feline friend, because of the saint’s association with learning, which would have appealed to humanists such as Desplà.

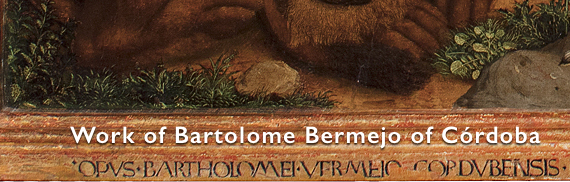

Signature (detail), Bartolomé Bermejo, Piedad with Canon Lluís Desplà, 1490, tempera on wood (Barcelona Cathedral)

Bermejo signed his painting on the frame with the words, “Opus.Bartolomei.Vermeio.Cordubensis” (Work of Bartolome Bermejo of Córdoba).[1] The all capital letter inscription is done in a classicizing manner, evoking antique Latin inscriptions. This may reveal Bermejo’s interest in ancient Roman culture, perhaps studying first-hand the Roman monuments found in Iberia. Because Bermejo’s patron was also a humanist antiquarian, the artist’s choice could have been Desplà’s.

Bermejo’s Piedad is an exceptional painting that embodies much of the artistic transformation and innovation taking place across different parts of Europe. His empirical approach to the representation of plants and animals was one shared by other artists of this time, like Leonardo da Vinci, and which he uses to create powerful symbolic messages about Christ’s sacrifice and the hope of salvation.