Dreamlike, imaginative, and inexplicable, Bosch’s landscape confounds our expectations of Christian art of the Renaissance.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 185.8 cm high, central panel 172.5 cm wide, wings 76.5 cm wide (Museo del Prado, Madrid). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker. We are especially indebted to the scholarship of Dr. Hans Belting and Dr. Joseph Koerner.

0:00:06.4 Dr. Steven Zucker: We’re in the Prado in Madrid looking at one of their most famous paintings. It’s enormous, and there’s a huge crowd around it. This is Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, or at least that’s the title that we call it now.

0:00:21.6 Dr. Beth Harris: We don’t know its original title. We don’t know the circumstances of its commission. And the real challenge for us is that as we walk through the museum, we see paintings from the Christian tradition, and they all have subject matter that we recognize. But when we get to Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, those traditions fail us.

0:00:43.4 Dr. Steven Zucker: But that’s not keeping an enormous crowd of people from enjoying this painting. If you stand over by the wall, you can just catch an oblique view of the outside. This is a painting made of three panels, and what you would have seen originally when this painting was closed was the exterior view.

0:01:03.0 Dr. Beth Harris: Triptychs were generally made for church altarpieces. We’ll see that this painting was clearly not meant for a church. We know that this was commissioned by a member of the court of the Duke of Burgundy, who was one of the wealthiest men in Europe. And common for the outside of triptychs, we see a scene in grisailles and shades of gray.

0:01:26.1 Dr. Steven Zucker: He’s giving us this eternal darkness. There is this large crystalline globe, which is the earth, and then just in the upper left corner, we see God the creator.

0:01:37.4 Dr. Beth Harris: God is holding a book. He looks very small and far away. And then there are two inscriptions. They read, “For he spake and it was done.” And, “For he commanded and they were created.”

0:01:49.7 Dr. Steven Zucker: So this is the moment when God has separated the land from the seas. You can see that there are plants, and they seem almost primordial. So this is the time before the creation of Adam and Eve, but we’ll see that on the inside. Let’s open this up. The left panel shows God, although here a very young God. So young, in fact, that he looks very much like Christ. Who’s holding the arm of the newly created Eve and is presenting Eve to Adam. What Bosch is representing is Adam taking in the beauty of Eve, but she doesn’t return his glance. She looks down demurely.

0:02:31.2 Dr. Beth Harris: Art historians have noted the touches of pink paint on Adam’s cheeks as though he’s flush with desire.

0:02:39.3 Dr. Steven Zucker: And look at the way that this Christ-like figure looks out at us. And it’s almost as if he’s questioning: Do you look at Eve in the same way that Adam does? Is there a desire in your eyes as well?

0:02:51.8 Dr. Beth Harris: “God blessed Adam and Eve and said to them, be fruitful and increase in number, fill the earth and subdue it, rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.” Now, what we would expect to see next would be the temptation of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden by the serpent, and it’s that event of eating the apple from the Tree of Knowledge that sets in motion the history of mankind, the expulsion from the Garden of Eden, the presence of death and sin. So it’s the critical moment, but it’s not here. If we look toward the upper right, we see a tree with a serpent around it, which certainly alludes to the idea of the temptation, but we don’t see the actual temptation. Behind them and around them we have this lush garden filled with trees and vines and fruits and animals.

0:03:47.2 Dr. Steven Zucker: And we also see in the center of a pond this almost flesh-colored construction that seems to be both stone and animal and plant at the same time. It’s a wildly inventive structure.

0:04:01.4 Dr. Beth Harris: It seems to me that these evoke growth and fecundity. There are forms that give birth to other forms from which yet other forms emerge. There’s this constant growing, this constant emerging of life, and this sits on precious stones in the middle of this body of water, animals perch on it.

0:04:24.5 Dr. Steven Zucker: And in fact, the entire scene is filled with life. It’s filled with plant and animal life. Some that we recognize, some that we don’t recognize. Some mythic, some entirely invented. In the very center of this fountain is an aperture, and perched in the hole, barely visible, is an owl.

0:04:43.0 Dr. Beth Harris: He peers out. We could almost read this pink circular form as an eye and the black circle as the pupil and the owl peering out from that. All of this at the very center of this panel, this creature of darkness, of evil, seems to look down at God introducing Adam to Eve.

0:05:05.1 Dr. Steven Zucker: The central panel is overwhelming. It shows this deep landscape. Here we see a foreground, a middle ground, a background, and then even more distant lands beyond that. And every segment of this landscape is packed with creatures, people, and things. There is so much to look at.

0:05:26.4 Dr. Beth Harris: We see hundreds of figures who appear to be in a land of pure, sensual pleasure. There is no death, there’s no growing old, there are no children, but what we do see are often oversized animals, oversized fruits, human beings insatiably gobbling, eating, licking the fruit. The fruit sometimes appears where someone’s private parts would be. Natural forms, plants, spring from the fruit. Flowers, birds perch on them. Figures float in fruit along bodies of water. Figures are engaged in sexual activity, but it’s all very confused. All of these different forms interact in myriads of different ways.

0:06:16.4 Dr. Steven Zucker: Needless to say, this is not what you would expect to see by an artist who was deeply religious within a society that was deeply Christian. This is shocking. It’s so unexpected. There is no parallel in the entire history of Western art.

0:06:33.0 Dr. Beth Harris: Bosch confounds our ability to even talk about what we see. His imagination has run wild. He’s just invented so many things here that we could never even have thought about in our wildest imaginations.

0:06:49.6 Dr. Steven Zucker: One art historian has suggested that one of the things that Bosch is attempting to do in this painting is to elevate the visual arts to the level of creativity that was permitted in literature. That is, there was a long tradition that allowed authors to be wildly inventive. But because painting is representative, and because painting had always been at the service of religion, it was inherently more conservative. This line of thinking suggests that Bosch is here creating room for the level of creativity that one finds in literature.

0:07:23.2 Dr. Beth Harris: And we should see here something that helps us move from left, from the creation of the world, to the right panel, which as we’ll see represents hell, but all that we have here are frolicking, oblivious figures engaged in all sorts of carnal pleasures. This is not at all what we expect to see in the central panel of a triptych that begins with the creation and ends with hell.

0:07:50.2 Dr. Steven Zucker: Art historians have tried to solve this every which way. But one of the most compelling theories is that the central panel is an alternate story. What if the temptation had not taken place? What if Adam and Eve had remained innocent and had populated the world? And so is it possible that what we’re seeing is that reality played out in Bosch’s imagination? But I want to step back because although it is wonderfully playful and wonderfully inventive and just an incredible thing to look at, it would have been deeply troubling to Bosch’s generation. That is, Bosch would not have looked at this kindly. His society would have looked at this as sinful, even though the people that are being represented here didn’t understand sin.

0:08:37.3 Dr. Beth Harris: In the fountain, in the center of the panel, we see an orb that’s cracking and this fabulous fountain that rises above it. But if we look carefully at the circle where we saw the owl in the first panel, we see a highly erotic scene that makes more explicit the kind of sexuality that’s being portrayed in the central panel. This is a kind of riotous, unlimited sexuality that doesn’t have at its end procreation. This is sensual pleasure for its own sake.

0:09:13.4 Dr. Steven Zucker: And of course, procreation was the only kind of sexuality that the church at this time found acceptable. If we look at the lower left corner of this panel, we see a group of people who are looking directly at the creation of Adam and Eve in the panel on the left.

0:09:29.7 Dr. Beth Harris: As though they’re saying, “This is where it all began. Here’s Adam and Eve, our first parents.”

0:09:35.5 Dr. Steven Zucker: There are two oversized owls that frame this central panel. Animals that are meant to signal the presence of evil.

0:09:43.1 Dr. Beth Harris: There’s so much in this central panel that is inexplicable, dreamlike, imaginative, and its scenes of rampant sexuality, of sensuality and pleasure, have an effect on the viewer and almost implicate us in any enjoyment that we might be taking in looking at these scenes of pleasure. We begin to feel guilty ourselves.

0:10:11.3 Dr. Steven Zucker: We’ll remember that in the leftmost panel, God is looking out at us, and he seems to be gauging our reaction to what we’re looking at.

0:10:19.7 Dr. Beth Harris: The far right panel, which is hell, is much more in line with other images of hell and damnation from the long history of art.

0:10:29.7 Dr. Steven Zucker: Although I might add, through the eyes of Bosch, who is not only extraordinarily skilled in his ability to represent, but what he represents is constructions of the most outrageous kind that they’re almost impossible to describe.

0:10:44.6 Dr. Beth Harris: The largest figure is a figure that art historians call the “Tree Man”. His legs look like the branches of trees with more branches growing from them. But where we might see his feet, we see two unsteady boats in the water with figures in them, suggesting that there’s an inherent instability to this figure who can barely balance in this way.

0:11:08.6 Dr. Steven Zucker: And while at one moment his body seems as if it’s made of wood, his torso is broken, cracked, almost as if it was the shell of an egg. And so it is both bark and eggshell at the same time, and then that body is itself pierced by its own branches. And that’s before we even recognize that there’s an entire tavern scene within the cavity of the body, and that there’s a face that’s turning around and looking back at us.

0:11:37.9 Dr. Beth Harris: So we have this tavern scene, these associations of drinking, of gambling, of prostitution, taking place within the body of this figure. And then on top of his head, this round surface with figures moving in a circle around this bagpipe, which has also suggestions of sexuality.

0:11:58.6 Dr. Steven Zucker: The bagpipe is monstrous and oversized. In fact, Bosch uses oversized musical instruments as instruments of torture, which we see throughout this panel. There’s an enormous harp on which a man is being crucified. There are expressions of particular people’s sins that are related to their tortures.

0:12:19.3 Dr. Beth Harris: For example, gambling we see in the lower left. We see dice, we see cards. So things that are pleasurable in life become sources of interminable pain and suffering in the eternity of hell.

0:12:33.5 Dr. Steven Zucker: Here it’s night and the flames are shown vividly against the dark sky. The ruined buildings are shown in silhouette. There’s smoke rising, violence everywhere. There is no escape.

0:12:46.8 Dr. Beth Harris: This is absolutely terrifying, these dark armies moving through the night, being led over bridges, through tunnels.

0:12:56.9 Dr. Steven Zucker: In the lower right corner of the panel, there’s a particularly menacing figure. This devil has enormous eyes like an owl, and he’s also got a bit of a beak. He’s devouring a body who has blackbirds flying out of his anus, and this devil sits on a throne that’s also a kind of toilet and below is a bubble that he’s excreting which figures that he’s devoured seem to be swimming through. It is this awful grotesque scene.

0:13:26.0 Dr. Beth Harris: And below that, a pit in which we see the faces of figures trapped there while another figure seems to defecate into this pit while another figure vomits into it. Nearby, a female figure is embraced by an animal and she seems to be the sin of vanity as she looks at her reflection in a mirror, but that mirror is formed on the rear end of a demon.

0:13:54.1 Dr. Steven Zucker: Multiply those descriptions by a thousand, and you have a sense of the complexity, the detail, and the horrific inventiveness of this scene. But I want to go back to the Tree Man for a moment, because he’s looking out, perhaps at us, but if you look at the pupils of his eyes, he seems to be looking back perhaps to Adam and Eve, to Adam’s lustful look at Eve.

0:14:16.5 Dr. Beth Harris: It is as though the desire that is aroused in Adam by the sight of Eve is the originary moment of the story of mankind.

0:14:26.9 Dr. Steven Zucker: In this representation, we don’t need the apple. We don’t need the serpent. All we need is Adam’s lustful gaze as he’s introduced to Eve.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (inner panels), 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

“But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked.

“Oh, you can’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.”

“How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice.

“You must be,” said the Cat, or you wouldn’t have come here.”

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

Deciphering the indecipherable

To write about Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych, known to the modern age as The Garden of Earthly Delights, is to attempt to describe the indescribable and to decipher the indecipherable—an exercise in madness. Nonetheless, there are a few points that can be made with certainty before it all unravels.

The painting was first described in 1517 by the Italian chronicler Antonio de Beatis, who saw it in the palace of the counts of Nassau in Brussels. It can therefore be considered a commissioned work. The fact that the counts were powerful political players in the Burgundian Netherlands made the palace a stage for important diplomatic receptions and the work must have caused something of a sensation with its viewing audience, since it was copied, both in painting and tapestry, after Bosch’s death in 1516.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (outer panels), 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

We can assume, therefore, that Bosch’s bizarre lexicon of human congress must have held some appeal, or some meaning, for a contemporary audience. In a period marked by religious decline in Europe and, in the Netherlands, the first blush of capitalism following the abolition of the guilds, the work has often been interpreted as an admonition against fleshly and worldly indulgence, but that seems a rather prosaic purpose to assign to a highly idiosyncratic and expressively detailed tour-de-force. And, indeed, there is very little agreement as to the precise meaning of the work. It is a creation and damnation triptych, starting with Adam and Eve and ending with a highly imaginative through-the-looking glass kind of Hell. No one really knows why Bosch imagined the world in this particular way.

Here’s what I think. What concerned Bosch, in his triptych of creation, human futility and damnation (the Garden of Earthly Delights is a modern misnomer for the work), was the essentially comic ephemerality of human life. Allow me to explain.

God (detail of outer panels), Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid; photo: Vincent Steenberg)

The outer panels

When the triptych is in the closed position (above), the outer panels, painted in grisaille (monochrome), join to form a perfect sphere—a vision of a planet-shaped clear glass vessel half-filled with water, interpreted to be either the depiction of the Flood, or day three of God’s creation of the world (which has to do with the springing forth of flowers, plants and trees, in which case he’s guilty of heedless over-watering).

A tiny figure of God, holding an open book, is found in the uppermost left corner of the left panel, and the inscription that runs along the top of both panels can be translated to read “For he spoke, and it came to be; he commanded, and it stood firm,” which is from Psalm 33.9. If one thinks of the outside panels as the end of the entire pictorial cycle, rather than its beginning, then this image could easily be a depiction of the Flood, sent by God to cleanse the earth after it was consumed by vice.

Detail, Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (outer panels), 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

This path towards vice is mapped in the inner panels of the triptych. The outer panels are therefore intended to provoke meditative purgation, a cleansing of the mind. It should be pointed out that this work, like Bosch’s Haywain triptych (also framed by a creation and damnation scene), is a triptych only in form; neither depict the conventional arrangement of a tripartite altarpiece because their center panels do not include religious figures or even religious scenes. What Bosch seems to have invented is an entirely new form of secular triptych, one that functioned kind of like a Renaissance home theater package for wealthy patrons.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (first panel), 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

The first panel: God Introduces Eve to Adam (and all hell breaks loose)

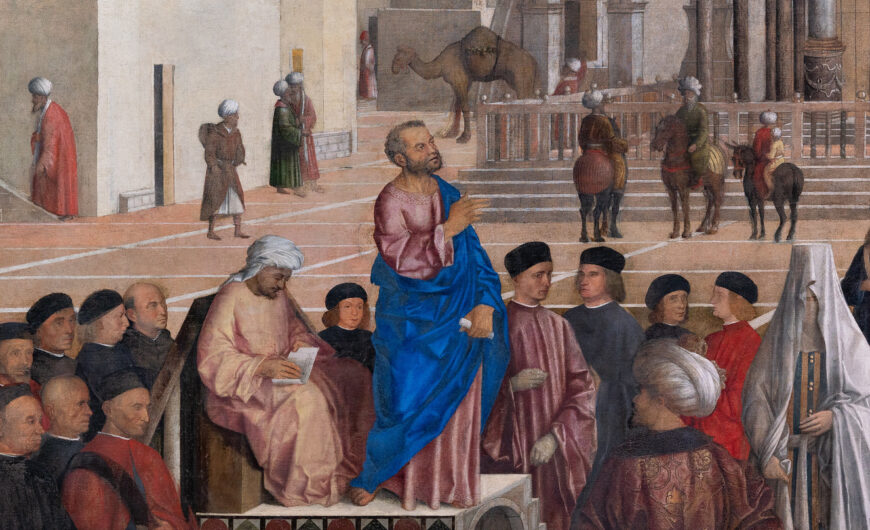

The first panel depicts God, looking like a mad scientist in a landscape animated by vaguely alchemical vials and beakers, presiding over the introduction of Eve to Adam (which, in itself, is a rather rare subject). Although they are precisely located in the center foreground, in scale Adam and Eve—as well as God—are precisely as important as the other creatures in this paradisiacal garden, including an elephant, a giraffe (straight out of Piero de’ Cosimo) a unicorn and other more hybrid and less recognizable animals, along with birds, fish, other aquatic creations, snakes and insects.

The introduction of woman to man, in this setting, is clearly intended to highlight not only God’s creativity but human procreative capacity. In the hierarchy of God’s handiwork, Adam and Eve represent his most daring achievement, as though after he’d made everything else he thought he needed to leave a signature on the world in which he could recognize himself. It’s a matter of conjecture, when one proceeds to the central panel, as to whether Bosch is saying that the creation of man, on whom God conferred free will, might have been a divine mistake.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (central panel), 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid; photo: 84user)

The central panel: People nakedly cavort (and all hell breaks loose)

This is the panel from which the title Garden of Earthly Delights was derived. Here Bosch’s humans, the offspring of Adam and Eve, gambol freely in a surrealistic paradisiacal garden, appearing as mad manifestations of a whimsical creator—sensate cogs of nature alive in a larger, animate machine. It is a matter of divided opinion as to what, exactly, the humans are actually doing in this delightful, dense and nonsensical landscape, alive with a dizzying array of some of Bosch’s most delectable creatures and dotted with his alembic architecture. It is almost as though he imagined the world of creation as a terrific Willy Wonka series of machines with humans as their product.

Detail, Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (central panel), 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid; photo: Vincent Steenberg)

Given Bosch’s emphasis on nude figures, some of which are engaged in amorous activities—although none in flagrante—this central scene has often been interpreted as a warning against lust, particularly in conjunction with the third panel, depicting Hell (the Spanish Hapsburgs, in fact, referred to the work as “La Lujuria“—lust). I wonder though. Bosch’s depiction of humans cavorting in the elemental world of God’s creation, seems, to me, less inculpatory than simply a commentary on the fact that there’s little to differentiate man from animals from plants.

Detail, Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (central panel), 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid; photo: Vincent Steenberg)

Many figures appear in all sorts of chrysalis states, or inside eggs or shells, and are fed ripe berries by birds or strange hybrid creatures; in the middle-ground some kind of procession of men, riding on various animals and accompanied by birds, circles a small lake of bathing maidens. It’s true that some unlikely human orifices are stuffed with flowers, but there is no explicit sex in this panel—just a gluttonous consumption of varieties of berries that have, by some, been linked to the pervasively hallucinogenic atmosphere (magic berries instead of magic mushrooms). In the end, there is folly and there is much that is visceral, but there’s no real vice.

Detail, Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (central panel), 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid; photo: Vincent Steenberg)

Instead, what Bosch appears to be doing is contemplating man’s place in the greater divine machine of nature. Maybe he’s saying, as Lucretius did, that all matter is made of atoms that come together for a time to form a sensible thing and, when that thing dies, those atoms return to their origins to reconfigure in some other form. This breaking and becoming is the nature of nature, and man in nature, is not differentiated by anything OTHER than his free will, his concern for his own behavior. Our reason is our undoing. Every man’s hell is only what he can imagine, and Bosch was more imaginative than most. His was a highly singular and idiosyncratic talent, and Bosch was really no more a product of his own time than he would have been of any other time. However, his ability to visualize hallucinatory landscapes made him extremely popular, three centuries later, with surrealists like Salvador Dali, who was also a virtuoso imagineer of nightmarish other-worldly worlds. I would venture to guess that Lewis Carroll must also have been a fan.

Panel of hell (detail), Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (third panel), 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid; photo: Vincent Steenberg)

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (third panel), 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

The third panel: finally, all hell breaks loose

Bosch saves the best for last. Earlier visions of Hell, if indeed that’s what Bosch intended here, are pretty tame in comparison to this. Against a backdrop of blackness, prison-like city walls are etched in inky silhouette against areas of flame and everywhere human bodies huddle in groups, amass in armies or are subject to strange tortures at the hands of oddly-clad executioners and animal-demons.

Dotted about are more crazy machine-like structures that seem designed to process human flesh. Some of these are strikingly disturbing. Near the center, a bird-like creature seated in a latrine chair, like a king on a throne, ingests humans and excretes them out again; nearby a wretched human is encouraged to vomit into a well in which other human faces swirl beneath the water.

Panel of hell (detail), Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (third panel), 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid; photo: Vincent Steenberg)

In general, the bodies purge themselves or are purged of demons, black birds, vomitus fluids, blood; as in any good Boschian world, bottoms continue to be prodded with various instruments. But the general emphasis is on purgation.

Overall, there is a marked emphasis on musical instruments as symbols of evil distraction, the siren call of self-indulgence, and the large ears, which scuttle along the ground although pierced with a knife, are a powerful allusion to the deceptive lure of the senses. In fact, many of the symbols and the tortures here are pretty standard in the catalogue of the Seven Deadly Sins, in which our senses deceive our thoughts into self-indulgent over-consumption.

Panel of hell (detail), Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (third panel), 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid; photo: Vincent Steenberg)

One key element here, however, requires some explication—the central, Humpty-Dumpty-ish figure who gazes out of the scene, his cracked-shell body impaled on the limbs of a dead tree. The art historian Hans Belting thought this was a self-portrait of Bosch, and a lot of people believe this, but it’s impossible to verify. Still, it quite strikingly illustrates the presence of a controlling, human consciousness in the centre of all this tortured imagining. And this is where my interpretation parts ways with those who have come before.

Panel of hell (detail), Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (third panel), 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid; photo: Vincent Steenberg)

Because, while “Bosch’s” mind (if it is a self-portrait) might be distracted with thoughts of lust, symbolized by the bagpipe-like instrument balanced on his head (standard phallic stand-in), within the hollow of his body, a tiny trio of figures sit at a table as though dining. To me, these three figures are reminiscent of Genesis 18.2, in which God arrives at the door of Abraham, accompanied by two angels (all disguised as ordinary men) and Abraham, without question, offers them his humble hospitality. As his reward, God bestows a miraculous pregnancy on the aged Abraham and Sarah, declaring that, through this act, Abraham will father God’s chosen tribe on earth. This would also be consistent with Psalm 33.12: “ Blessed is the nation whose God is the LORD, the people he chose for his inheritance.” God then sends his angels (who are kind of early incarnations of FBI agents) to investigate matters in Sodom and Gomorrah, and Abraham uses this opportunity to intervene with God on behalf of the wickedness of the people there: “Will you sweep away the righteous with the wicked?” he asks.

It seems to me that this is the question the whole triptych asks—whether God, having made the world and having conferred on man both the blessing and the curse of free will, would destroy all of his creation in the face of human failing. This is the fundamental connection between these inner panels and the destructive flood depicted on the outer wings. Bosch’s lesson, if there is one, seems to be that we can choose good over evil or we can be swept away. Man proposes, God disposes.

Panel of hell (detail), Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (third panel), 1490–1500, oil on oak panels (triptych), 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid; photo: Vincent Steenberg)