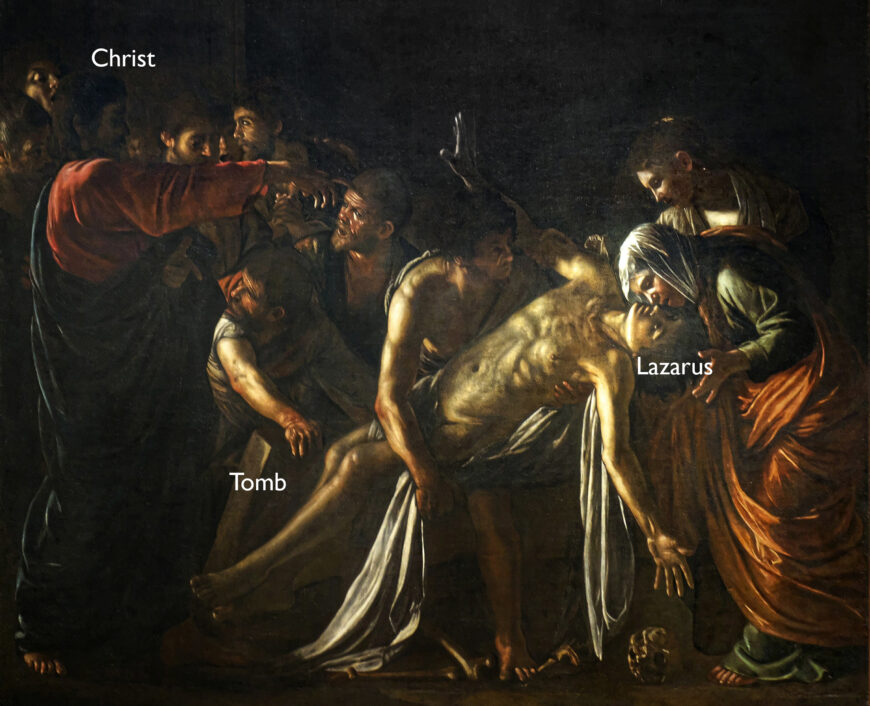

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Resurrection of Lazarus, c. 1609, oil on canvas, 380 x 275 cm (Museo di Messina)

Altarpieces during the Italian Renaissance typically presented their subjects and narratives clearly so that viewers might easily identify major figures and recognize the stories portrayed. At the beginning of the 17th century, Caravaggio proposed a radically different way of approaching religious narrative. Caravaggio’s Resurrection of Lazarus demonstrates the artist’s interest in rejecting artistic norms with a dark nighttime composition. Piecemeal illumination highlights a confusing selection of body parts on figures both important to the story and mundane. Life-sized figures crowd onto a narrow ledge in the lower half of the composition under yawning black emptiness. Though Caravaggio’s visual choices may seem idiosyncratic, they consistently address the needs of his patrons and advance religious meaning.

The altarpiece depicts the biblical story of a miraculous resurrection performed by Christ. One of Christ’s friends, a man named Lazarus, had been ill and died while Christ was away. When Christ returned, people were angry that he had not arrived earlier to heal Lazarus, but Christ denied Lazarus had died saying “I am the resurrection and the life. The one who believes in me will live.” Christ commanded the stone be removed from the entrance of Lazarus’ tomb and called “Lazarus, come out!” And Lazarus did, alive. [1]

Christ resurrecting Lazarus (detail), Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Resurrection of Lazarus, c. 1609, oil on canvas, 380 x 275 cm (Museo di Messina)

Caravaggio has depicted the story as a night scene. Lazarus’s body has been removed from the tomb; a bearded man lifts the tomb’s slab up from the floor. Christ stands in shadow on the left wearing red and blue pointing at Lazarus, whose nude body forms the center of the painting. Lazarus’s body begins to lift as he moves upright towards Christ. The miracle causes various reactions from the astonished onlookers, some of whom strain to see in the dim light.

Placing Christ in shadow

At first glance the Resurrection of Lazarus resembles the explosively dramatic compositions Caravaggio made at the turn of the 17th-century in Rome. He introduced the use of tenebrism to illuminate night scenes selectively. One might expect the painter to have chosen to place the most important parts of the scene in bright light and the less important elements in shadow, but Caravaggio often does the opposite. For example, in his Crucifixion of Saint Peter, he lit both Saint Peter and a faceless worker’s bottom in the same harsh spotlight, and in his Calling of Saint Matthew, he relegated Christ, the most important figure in Christianity, to the shadows behind Saint Peter’s yellow mantle.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Calling of Saint Matthew, oil on canvas, c. 1599–1600, 322 x 340 cm (Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome)

Caravaggio’s use of tenebrism and chaotic compositions require the viewer to search for the holy figures. His emphasis on poverty with the inclusion of figures in torn clothes with dirty bodies (the upturned feet of the worker in the Crucifixion of Saint Peter) coincided with 17th-century Catholic ideas of humility. Though theologically justifiable, Caravaggio’s pictorial choices differed so much from academic painting, compositions that adhered to notions of decorum and clarity. Annibale Carracci’s brightly colored academic painting the Assumption of the Virgin hung in juxtaposition between Caravaggio’s tenebristic Crucifixion of Saint Peter and Conversion of Saint Paul at the Cerasi Chapel at Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome. Instead of Carracci’s clarity, Caravaggio supplied visual puzzles. Similarly, his Resurrection of Lazarus asks the viewer to sort through distractions in order to find and focus on the holy story.

Left: Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Crucifixion of Saint Peter, 1601, oil on canvas, 230 x 175 cm (Cerasi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); center: Annibale Carracci, Assumption of the Virgin, c. 1600—02, oil on panel, 245 x 155 cm (Cerasi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome; photo: José Luiz, CC BY-SA 4.0); right: Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Conversion of Saint Paul, c. 1601, oil on canvas, 237 x 189 cm (Cerasi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The painting’s patrons

Caravaggio delivered the Resurrection of Lazarus to the church of SS. Pietro e Paolo in Messina, Sicily in 1609, just one year before his death at age 38. He was commissioned to create the work by Giovanni Battista dei Lazzari, a private citizen, and the Padri di Crociferi, the monastic order governing the church in Messina.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Resurrection of Lazarus, c. 1609, oil on canvas, 380 x 275 cm (Museo di Messina)

The Padri di Crociferi were an order of monks dedicated to caring for the terminally ill, particularly plague victims. Saint Camillus de Lellis founded the order in the late 16th century in response to the lack of compassionate care found at most contemporary hospitals. The work was risky; most patients died and the Crociferi suffered a high mortality rate themselves. Unable to guarantee medical recovery, the order focused on palliative care and were known as the fathers “del ben morire” (of the good death). Despite the difficulties, the order grew spreading through Italy. In the city of Messina, the Padri di Crociferi served at seven civic hospitals and gained in popularity so quickly they outgrew their church twice before Caravaggio was commissioned to provide the high altar of SS. Pietro e Paolo.

The story of Lazarus’s resurrection was a significant story in Catholicism both as a major miracle Christ performed on earth and also as a prefiguration. The miraculous resurrection particularly suited the church of the Padri di Crociferi, who regularly experienced the deaths of their patients and of their own brothers. The altarpieces in the lateral chapels flanking the high altar also dealt with healing. [2]

Intimate closeness in Caravaggio’s composition

Caravaggio’s composition differs in several major ways from standard Resurrection of Lazarus iconography. Each divergence aligns the painting with the Padri di Crociferi’s mission of healing. In Caravaggio’s painting, onlookers react with surprise and fear as the mottled golden body of Lazarus begins to rise out of its rigor mortis. Lazarus’ revivification is shown in process. Lazarus seems neither fully dead nor entirely alive. The loose brushwork can be interpreted as either the movement of his return to life and animation or the decay of death decomposing the corpse. [3]

Caravaggio visualized Lazarus’s position between life and death quite plainly. He has underscored the prefiguration of Lazarus’s resurrection with Christ’s by having Lazarus’s body in a T shape with outstretched arms echoing Christ’s attitude on the cross. Furthermore, Lazarus’s arms point towards the polarity of life and death. Under Lazarus’s left hand rests a human skull, as if he himself has dropped it. His right hand, newly invigorated once more and fingers flecked with light, reaches up towards Christ, the source of Christian life.

Left: Sebastiano del Piombo, The Raising of Lazarus, c. 1517–19, oil on canvas, 381 x 289.6 cm (National Gallery of Art, London); right: Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Resurrection of Lazarus, c. 1609, oil on canvas, 380 x 275 cm (Museo di Messina)

Renditions of the Resurrection of Lazarus story typically center Christ’s pointing gesture commanding Lazarus to emerge from the tomb. A 16th-century altarpiece painted by Sebastiano del Piombo using Michelangelo’s designs emphasizes Christ’s power over death. Lazarus sits still bound by burial clothes, looking up at the forceful figure of Christ. Onlookers turn away from the body; some hold their noses to avoid the smell of a body that had been decomposing in the tomb for several days.

Lazarus and his sister Mary (detail), Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Resurrection of Lazarus, c. 1609, oil on canvas, 380 x 275 cm (Museo di Messina)

Caravaggio’s composition repeatedly places figures in moments of intimate closeness. The central gravedigger lifts Lazarus’s body with tenderness, gazing towards his face. Lazarus’s sister Mary stands on the right cradling Lazarus’s head tenderly. Her open mouth nearly meets his. Their unshrinking familiarity with Lazarus’s body—which had been in the tomb for four days—turns them into models for the Crociferi’s compassionate handling of end-of-life illness. Like the Crociferi, Mary and the gravedigger overcome any revulsion towards a diseased body. [4]