Hans Baldung (Grien), Freiburg Altarpiece (open to the Coronation of the Virgin surrounded by two panels depicting the apostles), 1516, oil on wood panel, 253 x 232.4 cm (Freiburg im Breisgau Münster)

The German Renaissance artist Hans Baldung Grien is famous for many accomplishments, though not all of them served the greater good. Much of his art pushes us into the uncomfortable position of trying to hold two contradictory thoughts in our minds simultaneously, because his artwork can be as uplifting as it is hateful.

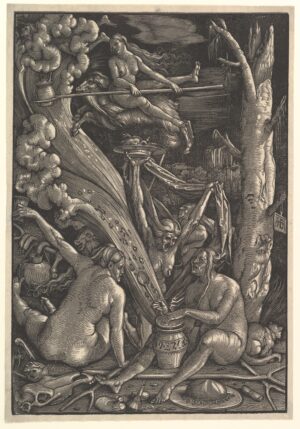

Hans Baldung (Grien), The Witches, 1510, chiaroscuro woodcut in two blocks, printed in gray and black, second of two states, 38.9 x 27 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Witches and saints

Baldung is most famous for his images of witches’ sabbaths, a pictorial type upon which he built his reputation, and which ultimately fed into the infamous witch hunts that flourished in the later 16th and early 17th centuries. However, in addition to depicting witches convening in forests and casting spells, he also represented female saints who were as gentle and lovely as his witches were violent and hateful.

Baldung was a leading artist of the German Renaissance, second in skill only to his older contemporary Albrecht Dürer, in whose workshop he was employed from around 1503–08. After serving in Dürer’s Nuremberg workshop, he became a citizen of Strasbourg in 1509, and shortly thereafter, in 1510, became an independent master in charge of his own workshop.

Baldung is sometimes called Hans Baldung Grien, a nickname that likely comes from his time in Dürer’s atelier. One of the theories about where “Grien” or Green comes from is a play on words. In 16th-century German, Grienhans or “Green Hans” means a devil, and much of Baldung’s work is indeed devilish.

Baldung’s joyous Freiburg Altarpiece, still at the high altar in the Freiburg Münster (Cathedral) is a delightful counterpart to his witches. The painting is a polyptych or many-paneled altarpiece, an object that adorned the altar of the church and directed the congregation’s celebration of the Eucharist (the ritual consuming of the bread and wine that marks Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross). The altarpiece is dedicated to the Virgin Mary, to whom the Freiburg Cathedral is also dedicated.

The Freiburg Altarpiece contains a total of eleven painted panels by Baldung and his team of assistants. It consists of a central panel with two stationary wings and two additional wings that open and close, as well as a predella, a horizontal panel running along the bottom. It has an opened and closed position, and it is painted on both the front and the back.

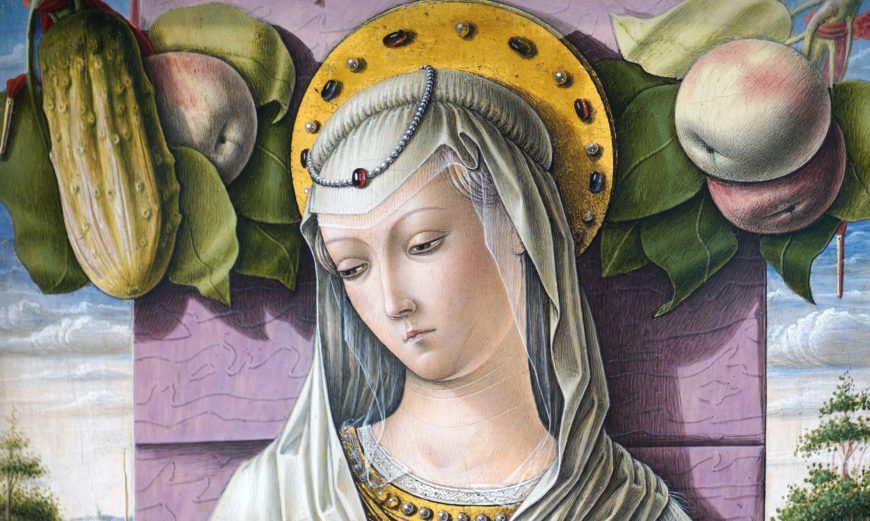

Coronation of the Virgin (detail), Hans Baldung (Grien), front central panel, Freiburg Altarpiece, 1516, oil on wood panel, 253 x 232.4 cm (Freiburg im Breisgau Münster)

Opened position

In the opened position, the central panel shows a subject known as the Coronation of the Virgin. The Virgin, as the protagonist of the painting, occupies the center. The Dove of the Holy Spirit, the third part of the Christian Trinity, hovers above her head. Fluffy clouds and tiny angels playing harps, flutes, violins, and trumpets populate the heavens above.

Coronation of the Virgin (detail), Hans Baldung (Grien), front central panel, Freiburg Altarpiece, 1516, oil on wood panel, 253 x 232.4 cm (Freiburg im Breisgau Münster)

Hans Baldung (Grien), Woman with downcast eyes, c. 1515, red chalk, 31.4 x 22 cm (Kunstmuseum Basel)

Christ and God the Father flank the figure of the Virgin as they place a crown on her head. Christ’s mantel flows loosely enough to reveal the wounds from the Crucifixion on his hands, feet, and side, reminding the viewers of the Eucharist.

Although the Virgin is about to be crowned Queen of Heaven, her prayerful hands point towards the earth, emphasizing her humility. This Virgin Mary is the sturdy, moon-faced, earthy Virgin so beloved in the art of Northern Europe going back to the 15th century. She has the high forehead and almond eyes that were the ideal of the time.

A drawing from c. 1515, which may have been a preparatory study, shows Baldung’s ability to convey innocence and youth.

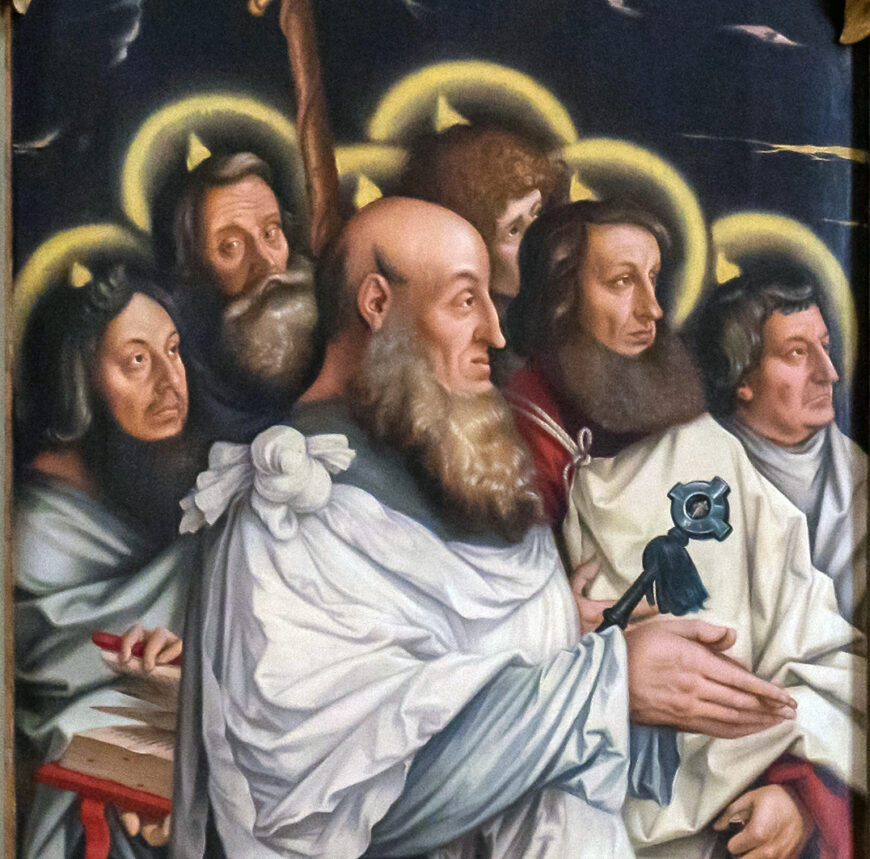

Saint Paul and other apostles (detail), Hans Baldung (Grien), open left panel, Freiburg Altarpiece, 1516, oil on wood panel, 253 x 232.4 cm (Freiburg im Breisgau Münster)

The Apostles in the wings are headed on the left by Saint Paul, identified by the hilt of his sword, and by Saint Peter, identified by his attribute, the key, on the right. Saints in this period could be identified by attributes that come from their legends. The flames of light around the apostles’ heads are the “tongues of fire” of the Pentecost (Acts 2:1–13), when Christ returned after his death to instruct his followers to preach to the world.

Saint Peter and other apostles (detail), Hans Baldung (Grien), open right panel, Freiburg Altarpiece, 1516, oil on wood panel, 253 x 232.4 cm (Freiburg im Breisgau Münster)

Closed position

At Christmas time, starting at Advent, the altarpiece was closed to show the four pictures of the Virgin Mary. The Virgin was the most beloved holy figure of the period leading up to the Protestant Reformations that began in 1517. Gothic Churches are often dedicated to “Notre Dame” or “Our Lady,” and the Virgin plays a central role in art, as in Baldung’s painting, where she is at the very center of the opened position and her life story is the exclusive subject of the panels in the closed position.

Hans Baldung (Grien), Freiburg Altarpiece (closed), 1516, oil on wood panel, 253 x 232.4 cm (Freiburg im Breisgau Münster)

Four panels on the life of the Virgin Mary

1. Annunciation

The stories begin on the leftmost wing with the Annunciation (Luke 1:26–38), when the Angel Gabriel comes to tell the Virgin Mary she will bear a son. Symbols that appear to be everyday objects help viewers understand the story. For instance, the burning candle symbolizes holy light, and the vase with Lily of the Valley symbolizes the Virgin herself. Earlier generations of scholars called these symbols “disguised,” though more recent scholarship has shown that the motifs were anything but “disguised” to the original viewers, who would have been able to “read” them fluently.

2. Visitation

The next panel shows the story of the Visitation (Luke 1, 39–56) when the Virgin (right) and Saint Elizabeth (left), mother of John the Baptist, share news of their pregnancies.

3. Birth of Christ

The Birth of Christ (Luke 2:6–20) follows. As in many paintings of this story, the Joseph is asleep, indicating that he became a father as an old man. Familiar Christmas-pageant elements are present: the donkey, the ox, and one of the shepherds. The deteriorating walls symbolize the falling away of the old era, the time before Christ, and the beginning of the new age. The setting of the scene at night adds poignancy and mystery.

Starting in the 15th century, Netherlandish artists such as Geertgen tot Sint Jans began depicting night Nativities.

Geertgen tot Sint Jans, The Nativity at Night, c. 1490, oil on oak, 34 x 25.3 cm (The National Gallery, London)

4. Flight into Egypt

Finally, the stationary panel on the far right depicts the Flight Into Egypt (Matthew 2:13–15). This is the story of the holy family’s flight to Egypt to escape the Massacre of the Innocents (Matthew 2:16–18). An angel standing on the donkey’s back pulls down a branch to offer dates to Christ. Symbolic animals and flowers amplify the story. On the ground we see a goldfinch, symbolic of the Passion, and a snail and butterfly, symbols for the Resurrection. The trilobed leaves of the strawberries stand for the Trinity.

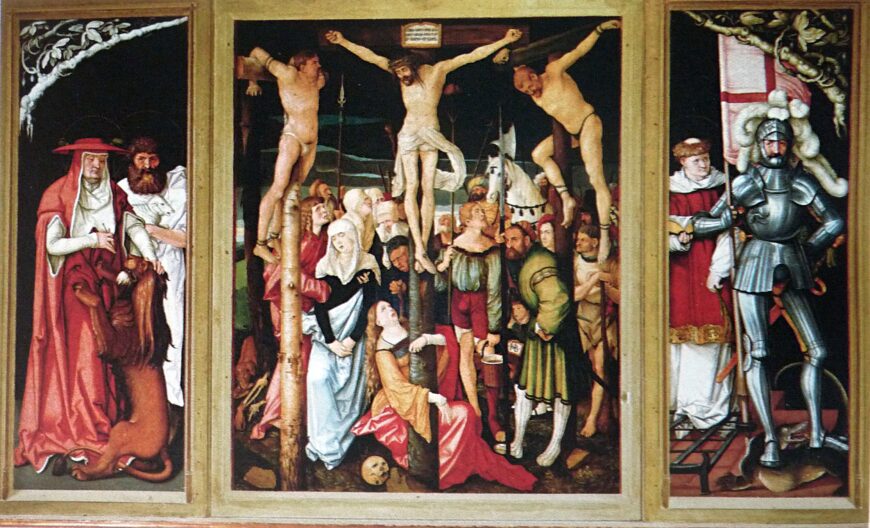

Rear panels

The rear panels show the Crucifixion in the center. On the top of the Cross is a sign in Hebrew, Greek, and Latin with the mocking epithet “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.” Mary Magdalene, the penitent sinner, embraces the base of the Cross. The skull at the bottom of the painting identifies the site as Golgotha, the place of the skull, the burial site of Adam according to tradition. Christ, as the new Adam, restores believers to life through his sacrifice on the cross. The thief to Christ’s right looks towards Him, indicating he has accepted Christ, while the thief to His left looks down, turning away from salvation.

Back of altarpiece, showing the crucifixion and saints, Hans Baldung (Grien), Freiburg Altarpiece, 1516, oil on wood panel, 253 x 232.4 cm (Freiburg im Breisgau Münster)

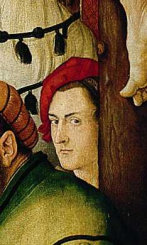

Self-portrait (detail), Hans Baldung (Grien), Freiburg Altarpiece (back), 1516, oil on wood panel, 253 x 232.4 cm (Freiburg im Breisgau Münster)

Like so many paintings of the time, the picture is made contemporary with pictures of people dressed in 16th-century garb. In a way, this is like the Broadway play Jesus Christ Superstar, which brought the story of Christ up-to-date and made it accessible by setting the story to rock music.

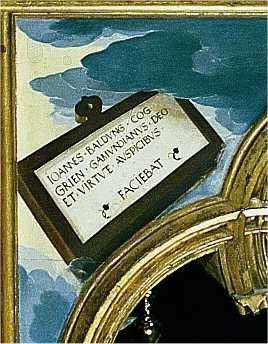

Artist’s signature (detail), Hans Baldung (Grien), Freiburg Altarpiece (back), 1516, oil on wood panel, 253 x 232.4 cm (Freiburg im Breisgau Münster)

The wings depict saints important for the local community. The left wing shows Saints Jerome and John the Baptist. Jerome, in red, was the patron saint of the Freiburg University. John the Baptist is identifiable with the Lamb of God on his arm. He was the patron saint of the Theology department at the University in Freiburg.

The right wing includes Saint George and Saint Lawrence, also identifiable through their attributes. George holds a lance with the flag of the city in his right hand. A dragon he famously slayed crouches beneath his feet. Behind him stands Saint Lawrence, patron saint of the Cathedral officials. He wears the costume of a deacon and holds the palm of martyrdom.

Baldung was not shy about calling attention to his efforts. In the Crucifixion scene he included a portrait of himself in a foppish a red beret, and he included his monogram in the hands of a small boy witnessing the Crucifixion.

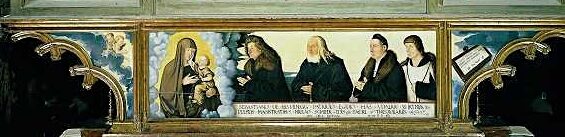

Predella (detail), Hans Baldung (Grien), Freiburg Altarpiece (back), 1516, oil on wood panel, 253 x 232.4 cm (Freiburg im Breisgau Münster)

Predella spandrel with signature (detail), Hans Baldung (Grien), Freiburg Altarpiece (back), 1516, oil on wood panel, 253 x 232.4 cm (Freiburg im Breisgau Münster)

Predella

The back of the predella portrays, and names, the four patrons who enlisted the services of Baldung and his workshop in 1512: Sebastian von Blumenegg, Aegidius Haas, Ulrich Wirtner, and Nikolaus Scheffer. They are each identified in a text beneath their portraits.

Baldung identified himself for a third time by signing his name on the spandrel of the predella: “Hans Baldung, called Green, from Gmünd, made this with God’s help and his own abilities.”

Piety and ego

The Baldung of the Freiburg Altarpiece creates an impression of both piety and ego. Not even Dürer made a habit of including a self-portrait, a monogram, and a verbose signature. The joy and loveliness of the picture adds to the complexity of this complicated artist.