Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Tower of Babel, 1563, oil on panel, 114 × 155 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Tower of Babel

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:04] We’re in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and we’re looking at Bruegel’s amazing painting, “The Tower of Babel.”

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:11] I really love this painting.

Dr. Harris: [0:12] Me too.

Dr. Zucker: [0:12] It’s just, there’s so much to look at, and it reminds you that before movies, before video, paintings could be incredibly entertaining. Here’s an image that gives us so many little narratives, so many things to look at.

Dr. Harris: [0:25] It really does reward close, prolonged looking.

Dr. Zucker: [0:29] The story comes from the Bible. Man decided to build a building that would be so high that it would reach into the heavens. It would reach God.

Dr. Harris: [0:37] God didn’t like that.

Dr. Zucker: [0:38] No, not one bit. The way that God took care of this was sort of wonderful and elegant. Humanity had been one people up to this time, but God said now he would divide man by language, so that when these men could no longer communicate with each other, well, the building couldn’t be built.

[0:55] But Bruegel is painting this now in the Renaissance, and there’s a different set of meanings. Yes, the Bible is the underlying story, but there’s the politics of his era.

Dr. Harris: [1:04] When we think about the Renaissance it’s hard not to think about the massive building campaigns. Bruegel himself is living in Antwerp, an incredibly wealthy city that trades in luxury goods.

Dr. Zucker: [1:16] So in some ways, this is about the dangers of man’s success.

Dr. Harris: [1:21] All the things that we build, all the things that we create, all of the power and wealth that we have is really nothing before God.

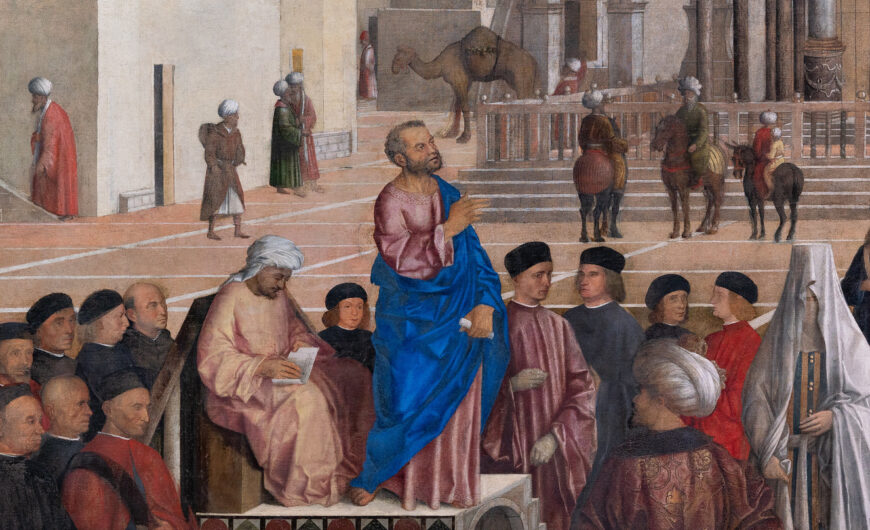

Dr. Zucker: [1:30] I think Bruegel makes that point rather nicely in the lower left corner of the painting where you see a king who’s presumably the man who’s ordering the building of this monument, and you see the workers who are actually carving stone, but also bowing down to him.

Dr. Harris: [1:43] There’s a kind of irony there, because as the workers bow down to him, we know that this tower that they’re building at his request is going to utterly fail, and in fact, it is failing right before our eyes, and before theirs if only they would notice it, too.

Dr. Zucker: [1:59] You mean even as it’s being built it’s so large that it’s also falling apart. In fact, the whole tower, although it seems so massive and so solid, is leaning to the left slightly, and it seems to be almost menacing the medieval city that’s just beyond it.

Dr. Harris: [2:14] There are some places where it seems very unfinished. I mean, if we look at the center there’s uncut rock, and then in other areas it looks completed, and other areas there’s scaffolding. There’s this sense that it’s rising and falling simultaneously.

Dr. Zucker: [2:30] You know, the whole thing really looks believable. You see winches and cranes.

Dr. Harris: [2:35] Hoists.

Dr. Zucker: [2:36] The basic construct itself seems to be loosely based on the Colosseum in Rome, which Bruegel would have seen when he visited that city. The whole thing really does seem as if it’s possible. There is this sense that here in the Renaissance man has become so capable. What are the dangers of that?

[2:53] It is an issue that, even in the modern era, we still grapple with. If you read science fiction, it’s always the robots and the computers that are the threat, right?

Dr. Harris: [3:02] Mm-hmm.

Dr. Zucker: [3:02] In a sense, this is an older take on technologies that were perhaps too big for us.

Dr. Harris: [3:08] Men look like ants everywhere here.

Dr. Zucker: [3:10] You get a sense of trade. You have a sense of materials coming from afar in the ships on the extreme right. You see a large castle, but it’s completely dwarfed by the massiveness of the tower itself.

Dr. Harris: [3:22] There’s a total sense of futility here. Everyone is doing something. Everyone is building, or carrying, or carving, or climbing, or doing something to make this happen, and yet as they’re so busy, we know that it’s all for naught. There’s a sense of a complete futility of human endeavor.

Dr. Zucker: [3:44] And even while we know that futility is central, there’s still an absolute love of the investigation of the building itself.

Dr. Harris: [3:52] We really have Bruegel the architect here. The tower is so fun. We want to go into it. We can see through it and into the arches and spaces and windows. We want to know what it’s like inside. It’s a dreamlike space that is incredibly seductive.

Dr. Zucker: [4:13] In a sense it’s a kind of entrapment. Bruegel is giving us this wonderful, seductive environment, and then he’s telling you, “You don’t want to do this. This isn’t all right.”

Dr. Harris: [4:22] It seduces us and entraps us and it’s really difficult to pull your eyes away from it.

[4:29] [music]

| Title | The Tower of Babel |

| Artist(s) | Pieter Bruegel the Elder |

| Dates | 1563 |

| Places | Europe / Western Europe / Belgium |

| Period, Culture, Style | Renaissance / Northern Renaissance |

| Artwork Type | Painting |

| Material | Oil paint, Panel |

| Technique |

Loading Flickr images...