Veronese described himself as a painter of figures. Judging by the throng depicted here, he clearly enjoyed it.

Paolo Veronese, Feast in the House of Levi, 1573, oil on canvas, 18′ 3″ x 42′ (Accademia, Venice)

[0:00] [music]

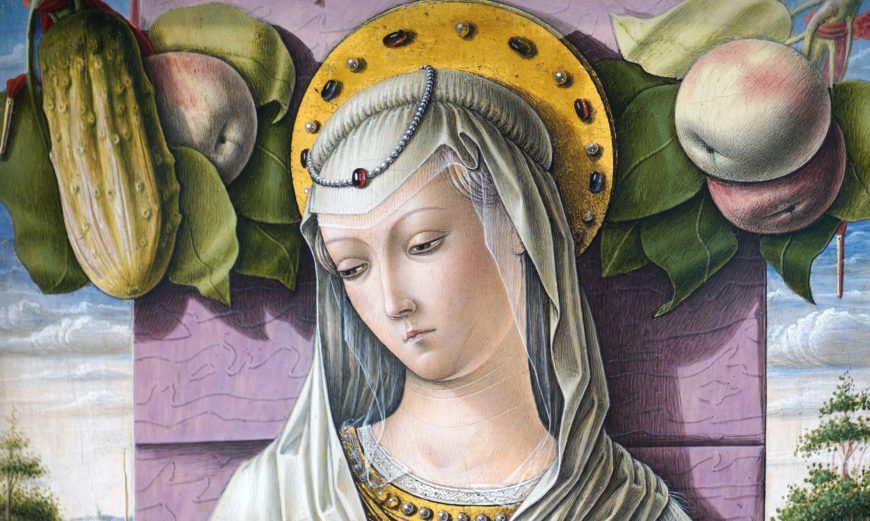

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re in the Accademia, the great fine arts museum in Venice. We’re looking at a massive painting by Veronese, one of the most important Venetian artists of the 16th century. This is “The Feast in the House of Levi.”

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:18] Except it’s not really, because it originally was meant to be, and I suppose still is, a Last Supper, but its title got changed. You may not even know it was a Last Supper because it’s hard to find the Last Supper in this painting.

Dr. Zucker: [0:34] True. First of all, there are a tremendous number of figures, and the architecture is so imposing. It’s so grand. The specific event being rendered is almost completely lost.

Dr. Harris: [0:46] It really does seem as though Veronese so enjoyed painting all of these figures around Christ and the apostles, much more than he was interested in the spiritual moment of the Last Supper.

[1:00] He’s got dozens of figures drinking and cavorting, welcoming others, serving people, entertaining. In fact, when Veronese described his profession, he said, “I paint and compose figures.” You can see the pleasure he had in painting so many different kinds of figures involved in so many different kinds of actions.

Dr. Zucker: [1:20] Even the most sacred, even the most important spiritual figures are engaged in action. Look at Christ, he’s turning to the figure at his left, as Saint Peter, who’s to his right, seems to be carving a piece of lamb to pass it over. These are the actions of real people.

Dr. Harris: [1:36] They’re real people having that Last Supper in the space inside this loggia. We’re looking at a three-part painting that might remind us of a triptych, with three arches.

[1:48] In the space between the front row of arches and the second row of arches, we see the Last Supper. In front, we have figures from Venice in the 16th century. They’re dressed like contemporary Venetians.

Dr. Zucker: [2:01] We’re seeing the cosmopolitan nature that was the Venetian city-state. Venice traded across the Mediterranean, east and west. It traded north. And so here, we have Germans on the right side of the painting, patricians. We have people wearing turbans on the left side of the painting. Venice is this intersection, this place where the world meets.

Dr. Harris: [2:21] Clearly, a sense of enormous wealth and privilege here. In some ways, it does look like a banquet and not a Last Supper.

Dr. Zucker: [2:28] That’s what concerned the Inquisition. Veronese was painting during the period that we know as the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation. There were people, especially in Northern Europe, that were beginning to question the church and its authority.

Dr. Harris: [2:40] Particularly the role of images in the church. There was a concern that images have a certain decorum, have a certain propriety and not distract the viewer.

Dr. Zucker: [2:52] Images played a really important role in what we call the Counter-Reformation, the attempt by the Catholic Church to re-energize itself, to deal with some of the corruption that had weakened it, but to really forcefully push forward Catholicism.

Dr. Harris: [3:05] Art was key to doing that. And if you have art that’s got lots of fun things to look at, and is distracting, and doesn’t help you focus on meditating on the spiritual moment or the devotional image that’s depicted, then art is not in the service of the church.

Dr. Zucker: [3:23] The Inquisition called a tribunal, where the artist was called to answer to what was considered a very serious lapse of judgment. It’s interesting to note that the church that commissioned the painting seems to have been fine with the final product, but the Inquisition was not.

Dr. Harris: [3:38] They questioned the artist, and they asked him what the various apostles are doing. They said, “Did anyone commission you to paint Germans, buffoons and similar things in that picture?” In other words, “Who’s responsible for this? Are you responsible for the ridiculous extravagance of this painting?”

Dr. Zucker: [3:57] Veronese’s response is interesting. He says, “The artist has the kind of license that a poet has,” that this is from his imagination. He was given a very large painting to paint, and he needed to fill it with figures.

Dr. Harris: [4:09] That’s right. He said, “I received the commission to decorate the picture as I saw fit. It is large and it seemed to me it could hold many figures.”

Dr. Zucker: [4:18] What the Inquisition had originally demanded was that some of the figures, specifically the dog, be changed, but Veronese said no. Instead, what he was going to do was simply change the title. It went from being a Last Supper to “Feast in the House of Levi.”

Dr. Harris: [4:34] Apparently, that satisfied the tribunal, it satisfied the church, it satisfied the artist, at least to some extent, in order to preserve his reputation.

[4:43] It occurs to me that when Leonardo painted “The Last Supper,” it was so much about removing everything that wasn’t necessary to portraying in an emotionally, spiritually, powerful way this moment when Christ said, “One of you will betray me,” and when Christ said, “Take this bread, for this is my body. Take this wine, this is my blood, and remember me.”

[5:06] This critical moment for the church and the creation of the Sacrament of the Eucharist. Leonardo distilled that, but Veronese exploded it and put it back into our world, and took it out of that timeless world that Leonardo had put it in.

Dr. Zucker: [5:23] That’s right. There is all the chaos of people paying attention to all different kinds of things, the way that a dinner party takes place. There is a kind of truth here that is different from the kind of truth that Leonardo presented.

Dr. Harris: [5:35] Did you see the cat under the table?

Dr. Zucker: [5:37] Yes.

Dr. Harris: [5:37] Right beneath St. Peter’s feet?

Dr. Zucker: [5:40] That’s great, maybe hoping for some of that lamb.

Dr. Harris: [5:42] And the dog is watching the cat. It’s filled with anecdote that really does distract from that message. On the other hand, you’re right, maybe it makes that message all the more palpable by embedding it in the reality of Venice in the 16th century.

[5:57] [music]

Paolo Veronese, Feast in the House of Levi, 1573, oil on canvas, 18′ 3″ x 42′ (Accademia, Venice, Italy)

Transcript of the trial: On Saturday, July 18, 1573, Paolo Caliari Veronese who lives in the parish of San Samuele, Venice was summoned to appear before the Holy Tribunal by the Holy Office [the inquisition], there he stated his name when asked. When asked what he did for a living, he responded, “I paint and make figures.”

Inquisition: Do you know why you are summoned here?

Veronese: No your honors.

Inquisition: Can you imagine what the reason is?

Veronese: I can.

Inquisition: Tell us.

Veronese: I was told by the priests, or rather by the Prior of SS. Giovanni e Paolo, whose name I don’t know, told me that he had visited here and that Your Great Lordships had commanded the Mary Magdalene replace the dog. I responded that that I would have happily done this and anything else for my and the sake of the painting, except that I did not believe that the figure of the Magdalene would look good there, for a variety of reasons, which I can speak to if I am given the chance.

Dog (detail), Paolo Veronese, Feast in the House of Levi, 1573, oil on canvas, 18′ 3″ x 42′ (Accademia, Venice)

Inquisition: What is the subject of the picture you are speaking of?

Veronese: It is a painting of the Last Supper, with Jesus Christ with his Apostles in the house of Simon.

Inquisition: Where is this picture?

Veronese: It is in the refectory of the Monastery of SS. Giovanni e Paolo.

Inquisition: Is it painted on the wall, on wood, or on canvas?

Veronese: Canvas.

Inquisition: How tall is it?

Veronese: Perhaps seventeen feet.

Inquisition: How wide is it?

Veronese: About thirty-nine feet.

Inquisition: Have you painted servants at the Lord’s Supper?

Veronese: Yes.

Inquisition: Tell us how many people there are, and each one’s activities.

Veronese: Below the owner of the inn, Simon, I put a carver, He came, I guess, for his own amusement, to observe the goings-on at the table. There are many other figures but I cannot remember, its been a long time since I finished the painting.

Inquisition: What was your intent regarding the man whose nose is bleeding?

Veronese: I intended him to be a servant, whose nose was bloody because of some accident.

Inquisition: And what did you mean by the armed man, clothed like a German, holding a halberd?

Veronese: That will take longer to explain.

Inquisition: Tell us.

Veronese: Painters take the same poetic license that poets and madmen take, and this is how I made these two soldiers, one drinking the other eating, at the foot of the stairs, though both ready for prompt action. It seemed appropriate to me that the wealthy owner of this house, a noble I understand, would have hired security such as these men.

Inquisition: And the figure dressed as a jester with a parrot perched on his hand, why did you represent him?

Veronese: He is decorative, as is customary.

Inquisition: Who are those at the Lord’s table?

Veronese: The twelve Apostles.

Inquisition: What is St. Peter doing, the first one?

Veronese: He is carving lamb, to pass it to the other side of the table.

Inquisition: And who is the other man, next to him?

Veronese: He holds a plate for St. Peter to fill.

Inquisition: What is he doing.

Veronese: He is picking his teeth with a fork.

Inquisition: Who do you believe was at the Last Supper?

Veronese: Christ was there with his Apostles. But there was more space, so I included other figures that I created.

Inquisition: Did anyone tell you to paint Germans, jesters, or buffoons in this picture?

Veronese: No. I was told to create the painting as I thought fit, it was large and could accommodate numerous figures.

Inquisition: Shouldn’t painters only add figures in keeping with the subject and the most important people portrayed? Do you freely follow your imagination without restraint, without good judgment?

Veronese: My paintings are made with all the consideration I can bring to bear on them.

Inquisition: Do you think it is appropriate that the Last Supper of Our Lord includes jesters, drunks, Germans, midgets, and the like?

Veronese: No, your honor.

Inquisition: Do you not know that Germany and other places are infested with heresy and that in such place they commonly fill their paintings with sacrilegious images, that denigrate the Holy Church and spread evil to the ignorant?

Veronese: Your Honor, that would be evil. I can only repeat what I previously stated, That I have followed what others, better than me, have done.

Inquisition: What has been done by those better than you? Which things?

Veronese: In the Pope’s chapel in Rome, Michelangelo rendered Our Lord, Jesus Christ, his Mother, Saint John and Saint Peter, and the court of heaven, all nude, including the Virgin Mary, in the midst movements without decorum.

Christ, Mary, and the Apostles (detail), Michelangelo, Last Judgment, 1536-1541, fresco, 1370 x 1200 cm (Sistine Chapel, Vatican City)

Inquisition: Don’t you understand that in a painting of the Last Judgment, clothing would not be worn, that there is no reason to paint clothes? Among those figures there is nothing except what befits the spiritual—there are no jesters, no dogs, no weapons, or any such silliness. Do you think this comparison, or any other that this example or any other justifies the way you painted your picture, and are you still certain that the painting appropriate to its subject?

Veronese: Your honor, I do not mean to defend it, but my intent was only good. I did not consider these issues enough, thinking that since the buffoons were outside the place where Our Lord sits, it was proper.

In the end, the judges decreed that the artist must correct his painting within three months from the day of the reprimand, in accordance with the judgment of the Holy Tribunal, and that the additional costs would be paid by Veronese.