Floating on a cloud above a harbor, the Virgin Mary’s graceful figure stretches upwards. Her resplendent brocade dress, blond curls, and the golden rays encircling her head transform her into a beacon of light. The pink rays of dawn cut through the clouds at the top, suggesting Mary is like the sun rising to light another day. Though she towers over the diminutive figures kneeling around her, she opens her arms in a welcoming gesture.

Mary tips her head downward, looking demurely toward her mortal companions and the sea below. As if the breeze from the sea could reach the clouds, her blue pallium (or cloak) billows outward, enveloping the faithful kneeling below her as though to offer comfort and protection. The artist, Spanish painter Alejo Fernández, shows Mary in hieratic scale (larger than the worshippers below) to denote her importance as the holy mother of Jesus and as a co-redeemer (or co-redemtrix) in the salvation of humankind.

Fernández made only the central panel with the Virgin Mary; other artists made the smaller flanking panels showing saints.

If we read The Virgin of the Navigators (or The Virgin of the Seafarers) closely, we can learn an enormous amount about Spain’s role in late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century exploration, trade and commerce, conquest and colonization, and slavery.

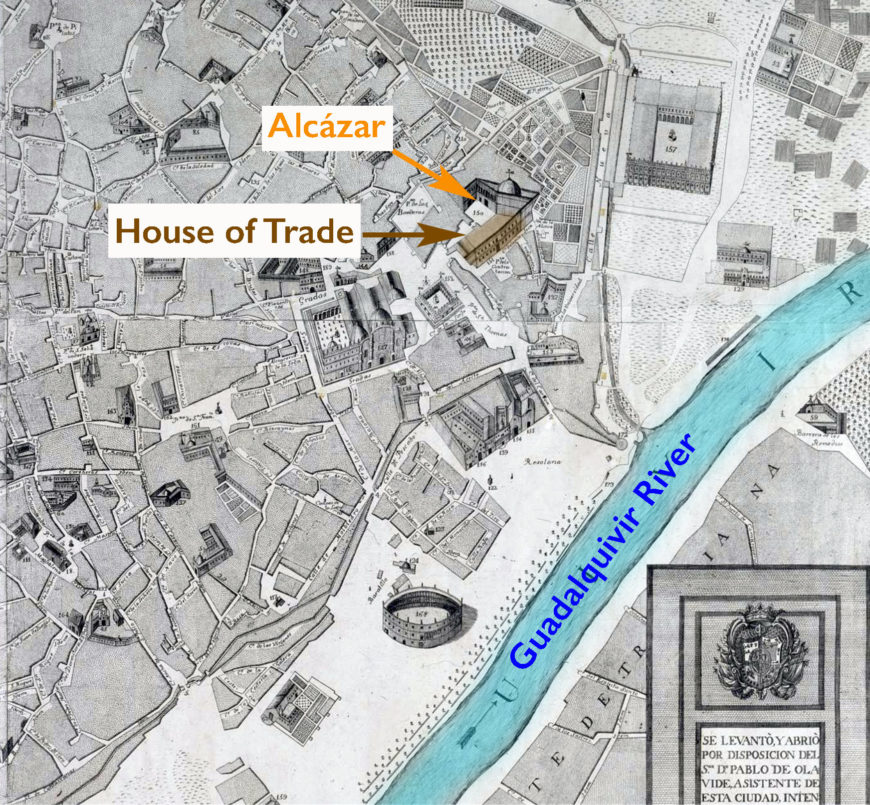

Francisco Manuel Coelho (designer) and José Amat (engraver), Topographical map of Seville (detail), commissioned by Pablo de Olavide, 1771, engraving and etching, 93.5 x 137 cm (Biblioteca Digital Hispánica)

Seville as a port city and the House of Trade

To understand the painting’s complex subject matter, it is important to know who commissioned it (the patrons) and where it was originally located.

The Virgin of the Navigators is the central panel of an altarpiece designed for a chapel in Seville’s House of Trade (in the Alcázar, a royal palace). The House of Trade (Casa de Contratación in Spanish) was established in 1503 by the Spanish Catholic monarchs, Isabel and Ferdinand, and played an important role in commercial activities between Spain and the Americas. Anything imported from—or exported to—Spain’s new American colonies passed through the House of Trade. Ships sailing to the Americas left from and returned to Seville (by way of the Guadalquivir, a navigable river), making the city an important hub of mercantile activity and international trade.

Members of the House of Trade commissioned the painting from Fernández, a renowned artist of the time who was highly regarded for his portraits and religious canvases. Fernández’s painting highlights the roles that Spanish rulers and the Catholic Church played in acquiring new territories, resources, and people, as well as their role in conquest, colonization, and commerce. The Virgin blesses these exploits, acting as a protectress to individuals associated with the House of Trade. Her luxurious dress—a brocade made of silk fabric and gold thread—also points to the Casa’s commercial activities. Brocades were costly import items, most likely imported from Italy (possibly Florence) or even further abroad. Clothing Mary in a costly dress emphasizes her importance and connects her to the commercial activities of the painting’s patrons.

The Virgin of Mercy in 1492

We see Mary with her arms open wide and her mantle wrapped around devotees. She is the Virgin of Mercy (in Spanish, Virgen de la Merced; in Italian, Madonna della Misericordia)—a subject that originated in the thirteenth century. Appearing this way, Mary is a symbol of protection, and images often include portraits of specific individuals or groups sheltered within her mantle (so wonderfully captured by the German name for this subject, Schutzmantelmadonna—“sheltering-cloak Madonna”). To have oneself portrayed alongside the merciful Mary was an effective way to demonstrate one’s piety and importance while garnering hope for her protection.

Some Marian subjects, including the Virgin of Mercy, increasingly communicated the idea that the holy mother (Mary) defends Christians from enemies. Mary had already developed these associations on the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal today) as Christian rulers tried to take territory from Muslim rulers (who had controlled regions of the Peninsula beginning in 711 C.E.). In 1492, Isabel and Ferdinand defeated the last Muslim stronghold on the Peninsula, in Granada. Muslims who were unwilling to convert were expelled, as were Jews. Campaigns against Muslims (in the Maghreb in North Africa and the Ottomans who ruled from Constantinople) continued into the sixteenth century. Stories of Mary’s divine intervention on behalf of Christians on and off the battlefield flourished.

1492 was also the year that Christopher Columbus, the Genovese explorer funded by Isabel and Ferdinand, journeyed across the Atlantic in search of a route to India. He would eventually land in the Caribbean, and his voyages would initiate the invasion and colonization of the Americas. The European discovery that millions of non-Christian Amerindian peoples lived in lands previously unknown to them also increased the fervent Christian belief that Christ’s Second Coming and the end of days was imminent.

Adding to the urgent need to prepare for the end of days were the religious transformations that resulted from the Protestant Reformation. According to tradition, in 1517, Augustinian monk Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to a church door in Wittenberg, demanding the reform of the Catholic Church. His action sparked a violent rift between Catholics and those who became Protestants, and theological and military battles ensued. Adding further chaos to this moment, King Henry VIII broke from the Catholic Church to form the Church of England after the pope refused to grant him a marriage annulment from his first wife (a Spanish Catholic). With these events in mind, Fernández’s Virgin of Mercy had special appeal as a protectress at a time when the Catholic faith was under threat.

Men (and women) of empire

In the painting, Mary offers solace and protection to those individuals directly involved in colonization and evangelization of the Americas. Many of them would have been in Seville, where Fernández worked, and it is possible that, as a well-known portraitist, he was able to paint some of their likenesses based on his observations of them in the city.

Let’s look first at the three men kneeling on the cloud in the foreground on the right side. The man at the right, who wears light leggings and a brilliant red cape, and is thought to be Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés whose actions led to the overthrow of the Mexica Empire in Central Mexico. The man at the left of this group, who wears a beige military-style outfit, is not firmly identified, but is almost certainly another conquistador. The man at the center, and slightly behind, with red hair and a longer beard, is likely King Charles I of Spain (who became the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V). These three men were directly involved in the conquest and colonization of the Americas (Charles was also actively fighting Protestants in northern Europe).

If we turn to the group in the foreground on Mary’s other side (our left), we see seven men and two women (these women remain unidentified, but likely represent members of the Spanish court).[1] The man with a cane is often identified as Amerigo Vespucci, the Florentine explorer who also gave his name to the Americas.[2]

The young man in red is likely Martín Alonso Pinzón, who along with his brother had accompanied Columbus on his first voyage and continued to participate in Spain’s imperial exploratory enterprises. The white-haired man on the left with the luxurious fur-trimmed gold colored robe has been identified as Columbus.

For a man known to have dressed very simply, Columbus’s expensive clothes seem out of character. Some scholars have suggested this finery explicitly connected him to the magus-king (one of the Magi—the kings who traveled from afar to offer gifts to the newborn Christ). In many images of the Adoration of the Magi, the magus-king wears similarly expensive clothing. The Magi also symbolized the extension of Christianity to all peoples because they journeyed from a far corner of the world. By the 1530s, this expansion of Christianity into new lands was actively occurring. Columbus himself was a Cristo ferens, or Christ bearer, bringing the gospel across the Atlantic (in fact his Spanish name—Cristóbal—echoes the Cristo in Cristo ferens).

Justifying conquest and evangelization

Indigenous peoples in the background (detail), Alejo Fernández, The Virgin of the Navigators, 1531–36, oil on panel (Reales Alcázares, Seville)

Behind the men and women associated with carrying out Spain’s imperial mission are smaller figures, who fade into the recesses of Mary’s cloak. Fernández painted them with darker skin, and did not differentiate their appearance—despite his being a celebrated portraitist. We can just make out that men kneel on the left, women on the right. They all wear simple white cloaks draped across their torsos. With the Spanish colonial mission in full swing by the 1530s, these figures undoubtedly represent the huge number of Amerindian peoples actively being converted to Christianity. Fernández has homogenized the diverse groups of Indigenous peoples, choosing not to differentiate them; the group symbolizes all Native peoples. The impression is that they have been brought under the protective mantle of Christianity (figuratively and literally), justifying the violence of conquest and colonization.

The Native people’s clothing also relates to Spain’s evangelization efforts. The simple white cloths are similar to those worn during baptism, the Christian purification rite that initiates someone into the faith. From a Christian perspective, millions of Native peoples in the Americas needed to be converted to prepare and save their souls before Christ’s Second Coming.

Detail, Alejo Fernández, The Virgin of the Navigators, 1531–36, oil on panel (Reales Alcázares, Seville)

Navigating the empire

In the bottom third of the painting, we leave the divine realm and wade into the earthly realm. A windy harbor is filled with the ships that made overseas exploration and expansion possible. Fernández has painted exquisite details that allow us to identify the types of ships. In the center is a nao (or carrack), with a wide, deep hull that could carry lots of people and cargo. Its size and maneuverability made it an ideal vessel for exploration and navigating wide-ranging trade routes. In the 1530s, you would have observed them leaving Seville as they embarked on journeys along the African coast to Asia or across the Atlantic. Columbus’s ship, the Santa María, was a nao, as were the ships of other famous European explorers such as Vasco da Gama and Ferdinand Magellan.

Also in the harbor are caravels, a galley, and other boats. Caravels were smaller and swifter than nao. Galleys, or the many oared ships that had a long history in the Mediterranean, were used as battleships and trade vessels in the Mediterranean and around the coast of Europe and Africa. All these ships would have been frequently observed in the Seville harbor because of the city’s key role in maritime trade, exploration, and colonial expansion. The Virgin of the Navigators makes good on her name: she protects those whose lifeblood is the sea.

Alonso Sánchez Coello (attributed to), View of the city of Seville, end of the 16th century, oil on canvas, 146 x 295 cm. (Prado, Madrid)

Seville and the history of slavery

As Fernández began painting The Virgin of the Navigators, conquistador Francisco Pizarro and his men were making advances on the Inka Empire in South America, which was fragile at that moment because rival brothers desired the throne. News from the Americas—such as Pizarro’s eventual defeat of the Inka ruler Atahualpa—passed through Seville, with much of it filtered directly through the House of Trade.

Seville and the House of Trade also played an important role in the history of slavery. As the Portuguese explored the west African coast in the 15th century, they started to enslave people and bring them back to Iberia. By 1462, Portuguese slave traders had established themselves in Seville, and the city became a central location in the selling and distribution of enslaved Africans, and had a sizable enslaved population itself. The House of Trade was directly involved in the slave trade, managing the ships and money generated from it. Fernández himself had at least several enslaved Black and Native individuals who were involved in his workshop.

The transatlantic slave trade began shortly before Fernández created The Virgin of the Navigators. In the Spanish and Portuguese Americas, in areas of extensive or total depopulation of Indigenous people (their numbers were greatly reduced by diseases introduced by Europeans from which they were not immune, and by cruel labor practices) enslaved Africans were brought in and forced to harvest precious resources, develop the land, and build. In 1526, the first Portuguese ship brought enslaved Africans to Brazil, initiating four centuries of slavery in the Americas. The Portuguese were quickly joined by the Spanish, French, British, and Dutch (among others) who participated in the horrifying brutality of the transatlantic slave trade.

Connecting seas

Ocean travel is what connects these far-off places and peoples together. The ability to navigate the ocean made Columbus’s fateful voyage possible, and led to the construction of ships that would carry enslaved peoples to the Americas. Navigation of the seas allowed certain European kingdoms, polities, and regions to amass impressive wealth, to develop trade relationships across vast distances, and to come into contact with cultures very different from their own (often with devastating consequences). Accurate cartography and navigation had become essential, and great advances were made by the 1530s. The House of Trade—members of which had commissioned Fernández’s painting—also established a school devoted to the vital skills needed by those individuals called to sea. It is perhaps fitting then that Fernández would transform his Madonna into a Virgin of the Navigators, offering those individuals who worked in the House of Trade a holy protectress, someone to champion their livelihood, along with Spain’s imperial ambitions and colonial desires.