Church of the Holy Cross, Pătrăuți Monastery, Moldavia, modern Romania, view from the southwest, 1487 (photo: Alice Isabella Sullivan)

This small church of the Holy Cross at Pătrăuți Monastery, located on the eastern slopes of the Carpathian Mountains, was built at a time of great turmoil in Christian history, a few decades after the fall of the city of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453. This event brought an end to the Byzantine Empire and redirected its resources and people to neighboring regions, like the principality of Moldavia.

By the second half of the 15th century, Moldavia emerged as a Christian frontier at the crossroads of Byzantine, Western European, Slavic, and Ottoman traditions. This resulted in adaptations and negotiations in local contexts. Architectural projects, like the church at Pătrăuți, reveal how Western medieval (often referred to as the Latin West) and Byzantine (often referred to as the Greek East) were creatively adapted and transformed in Moldavia in the so-called post-Byzantine period (after 1453).

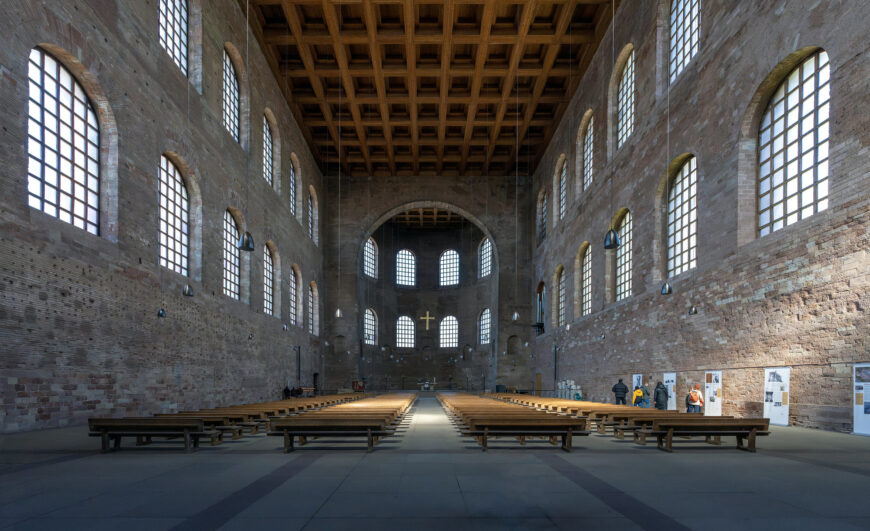

The monastic church at Pătrăuți provides a transcendent space where light changed to accentuate facets of the architecture, decoration, and ritual celebration, while drawing attention to the patron—Stephen III of Moldavia. Stephen ruled for close to half a century, and Pătrăuți is the earliest preserved church that demonstrates the new artistic style that he promoted in Moldavia through the building of over forty religious sites, mostly in the last decades of his rule. He turned his attention to religious building projects after dedicating the first three decades on the throne to the building of fortifications to protect his domains.

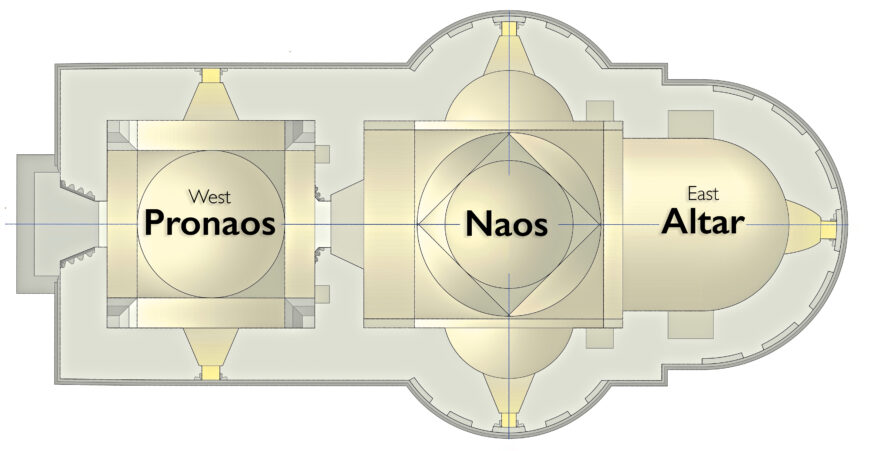

Plan, church of the Holy Cross, Pătrăuți Monastery, Moldavia, modern Romania, 1487 (source: Tudor-Cătălin Urcan)

The architecture

The church at Pătrăuți is small and was built out of local stone and rubble. It follows a triconch plan, which consists of a rounded eastern apse and two shallower lateral semicircular apses extending to the north and south. A square pronaos with a small window at the center of each of the north and south walls precedes the main liturgical space of the church. The main entryway is at the center of the west façade, and another small doorway leads from the pronaos into the naos, guiding the physical progression through the spaces. This passage from one room to the next focuses attention on the individual as only one person at a time can pass through each doorway. A shallow dome sits over the space of the pronaos, and a steeple-like dome with tall, rectangular windows pointing in the cardinal directions rises over the central space of the naos.

The church was designed and constructed by masons trained in Central-European workshops (from west of the Carpathian Mountains), however, the layout of the church adapts Byzantine church building traditions—in particular those found in the monasteries on Mount Athos. It was a particularly well-suited plan for Eastern Christian monastic worship as it allowed the monks or nuns to gather in the naos and amplified their singing during the celebration of the liturgy.

The murals

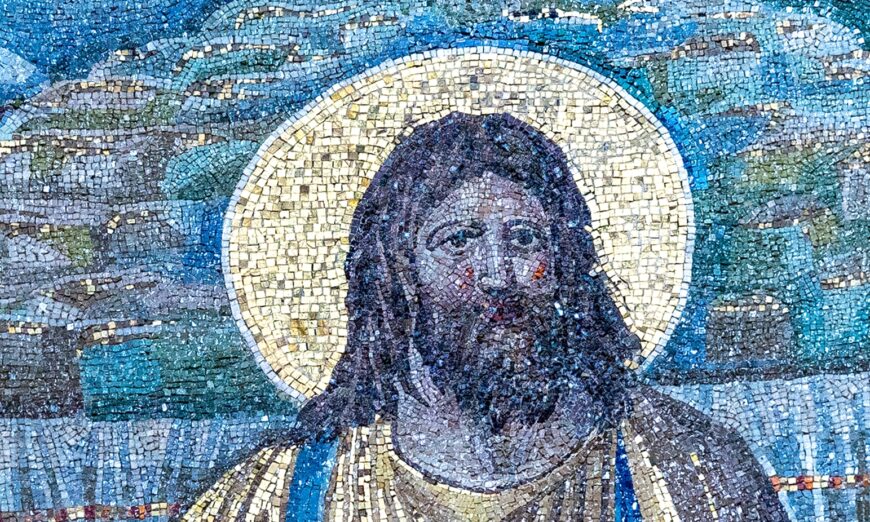

Like the layout of the church, the partly preserved mural cycles are similar to those found in Byzantine churches. They are brightly colored, cover the walls in their entirety from floor to ceiling, focus attention on Biblical scenes and Christian icons, and carry inscriptions in Greek. This suggests that artists trained in former Byzantine territories worked at the Moldavian court and on the church at Pătrăuți during the second half of the 15th century, being displaced from their homelands after the events of 1453.

Naos murals, view toward the west, church of the Holy Cross, Pătrăuți Monastery, Moldavia, modern Romania, 1487 (photo: Petru Palamar)

The interior murals represent the earliest extant example of Moldavian monumental church painting, whose program was adapted and expanded in other local churches and in the decades that followed. The sanctuary once displayed a monumental image of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child among angels, as found in other Byzantine contexts. Scenes from the life of Christ and the Virgin also cover the walls of the naos and pronaos at Pătrăuți, including Christ’s miracles. For example, painted at the top of the west wall of the pronaos and visible upon exiting the church, the mural of the Wedding Feast at Cana. Directly below this image is a distinctive medieval iconography with deep relevance in the Moldavian cultural context—the Procession of the Soldier Saints. The mural conveys a similar message of divine presence.

Mural of the Procession of the Soldier Saints, west wall of pronaos, church of the Holy Cross, Pătrăuți Monastery, Moldavia, modern Romania, 1487 (photo: Petru Palamar)

The mural of the Procession, painted in a long horizontal register on the west wall of the pronaos, above the main entrance to the church, shows a non-biblical scene with Emperor Constantine and the archangel Michael leading a cavalcade made up of thirteen mounted soldiers rendered in the guise of military saints. They ride toward a large cross in the sky before them, painted in the upper right corner of the composition. The Greek inscription near the cross states—“In this sign [the cross] you shall defeat your enemies”—recalling the account of the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, which marked Constantine’s turn to Christianity and subsequent protection of the Christian faith within the Roman Empire. Fighting under the sign of the cross also resonated in the Moldavian context of the late 15th century as the region was repeatedly under threat from neighboring powers, especially the Ottoman Empire, which was steadily advancing into Eastern Europe. The image evokes divine assistance in Constantine’s 4th century campaign, and, by extension, in Stephen’s contemporary struggles against the Ottomans.

Tympanum at the front (west) entrance with saints Constantine and Helena, Pătrăuți Monastery, Moldavia, modern Romania, 1487 (photo: Cezar Suceveanu, CC BY-SA 3.0)

On the exterior of the building, few painted images have survived. The Last Judgment takes up the entirety of the west façade, and an icon of Saints Constantine and Helena occupies the tympanum of the main entrance. Nothing else of the exterior decorations has been preserved.

The light

The architecture and mural cycles at Pătrăuți adapt Byzantine models, but other facets of the liturgical space reveal the inclusion of Western church-building traditions. This is evident in the masonry construction of the building and in the Gothic designs of the portals, window frames, and window tracery. These were a staple feature of Gothic workshops across Western and Central Europe and were routinely used in architectural designs. This building technique reached the Carpathian Mountains through traveling masons and the exchange of architectural drawings among workshops.

Sunlight effects observed in the church at Pătrăuți reveal how the building was designed to integrate astronomical knowledge prevalent in the Latin West. On certain feast days, sunlight has been observed to fall on specific scenes and liturgical furnishings, which it unites in symbolic ways, thus underscoring theological statements within the sacred space of the church. For example, the almost perfect east-west orientation of the axis of the church creates a “light path” around the equinoxes. Twice a year, in September and March/April, for about two weeks, the light entering the church in the afternoon passes through the aligned doors of the pronaos and naos to illuminate the altar. This alignment would have corresponded with the celebration of Vespers, which centered on Christ’s coming as Light into the darkness of the world.

Moreover, in the early morning on the summer solstice—the longest day of the year—the first ray of sunlight that enters the church illuminates the mural of Prophet Isaiah shown standing in the cylindrical drum of the naos’ dome. Isaiah displays an open scroll with an inscription drawn from Psalm 112(113):3 “From the sun’s rising to its setting, praise the name of the Lord!” As such, the text highlights the connection of Christian beliefs with sunlight.

Prophet Isaiah illuminated on the Summer Solstice, interior mural, drum of naos dome, Church of the Holy Cross, Pătrăuți Monastery, Moldavia, modern Romania, 1487 (photo: Gabriel-Dinu Herea)

More complex phenomena involve moving sunlight connecting different sections of the building and portions of the mural decoration, underscoring their theological importance during the liturgical celebrations and the devotional concerns of the patron who wanted to be perpetually remembered within the space at Pătrăuți. For example, during the celebration of the main liturgy on specific days, a sunray enters through the apse window and falls directly on the mural of the patron, situated on the opposite wall of the naos from the altar. As the liturgy unfolds, the sunray moves from the wall onto the floor, toward the altar, symbolically involving the patron in the celebration of the Eucharist.

As one of Stephen III’s earliest ecclesiastical projects, the church of the Holy Cross at Pătrăuți Monastery reveals innovation in the initial stages of church architecture in Moldavia in the post-Byzantine period. The church marks the beginning of an impressive series of religious projects in the region—consisting of monastic and parish churches, as well as chapels—that were designed in a new architectural vocabulary that incorporated aspects of Byzantine and Gothic church building and decorating traditions, alongside local forms. Among the extant monuments, Pătrăuți remains the key representative of Stephen’s early churches and an exceptional example of Eastern Christian church architecture in the post-Byzantine period.