Masaccio, Holy Trinity, c. 1427, fresco, 667 x 317 cm, Santa Maria Novella, Florence. Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re in Santa Maria Novella, an enormous Dominican church in Florence. We’ve just come in from a cloistered graveyard, and the first thing we see across this enormous expanse is Masaccio’s “The Holy Trinity with the Virgin and Saint John.”

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:21] Although this painting has a long and complicated history of being moved and restored, the doorway we walked in and the view that we got was likely the view that the public got in the early 15th century when Masaccio painted it.

Dr. Zucker: [0:36] Much of the rest of the church has changed. There may have been an altar in front of this painting. To the right, there would have been an enormous tramezzo, that is, a screen that would have blocked access to the inner sanctum of the church.

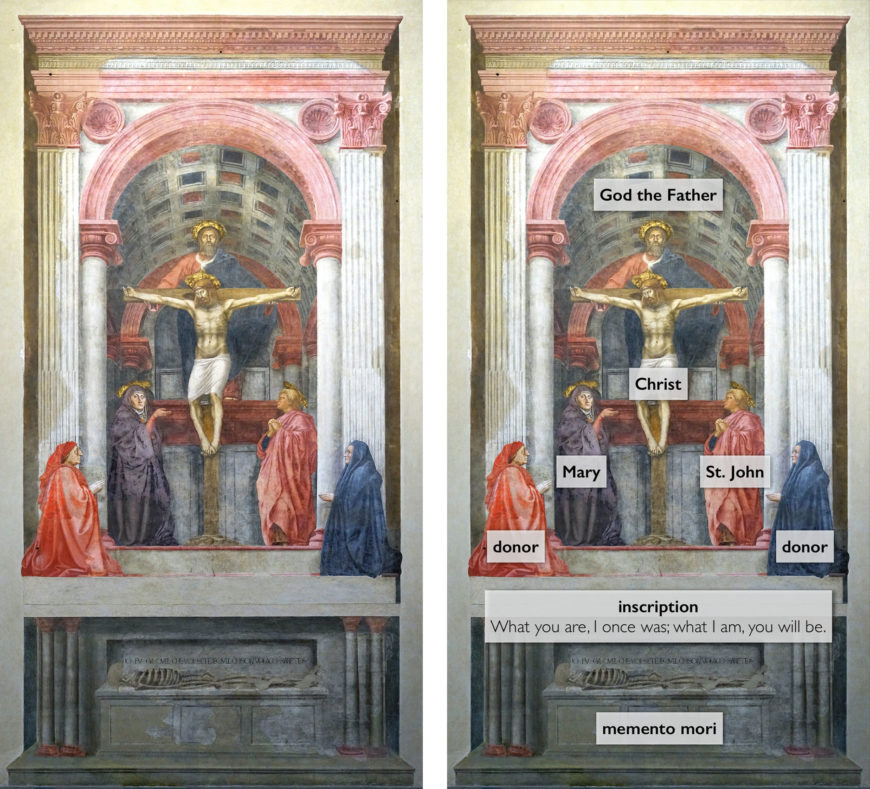

Dr. Harris: [0:50] The subject is the Holy Trinity. According to Catholic doctrine, God is God the Father, the Son — Christ, and the Holy Spirit.

Dr. Zucker: [0:57] This was a fairly standard motif, this elder figure that represents God the Father, the dove representing the Holy Spirit, and Christ on a crucifix. This is known as the Throne of Mercy. The idea is that this throne is the throne of judgment, that through Christ, man can be saved.

Dr. Harris: [1:15] On the side of the Holy Trinity, we see Mary, and she gestures to Christ and God. She acts as an intercessor, an intermediary between us and the divine world, and points to Christ and God.

Dr. Zucker: [1:29] Opposite her stands Saint John.

Dr. Harris: [1:31] All of those divine figures occupy the same space. Outside of that space, we see two kneeling figures: a man on the left, a woman on the right. These are the patrons who commissioned this fresco. If you look at them closely, you see that they look straight ahead.

Dr. Zucker: [1:48] And slightly up.

Dr. Harris: [1:49] They’re in a position of prayer, of contemplation.

Dr. Zucker: [1:54] Below this, we have a memento mori, that is, a reminder of death. We see a tomb, two columns on either side, and between that, a sarcophagus. Laid on top of that is a skeleton, and in back of it, as if carved into stone, is an inscription.

Dr. Harris: [2:10] “I was as you are, and what I am, you soon will be.” This is written in Italian, not in Latin, so not in the language of the church but in the everyday language of the people of Florence. It is reminding us that our time on earth is short, and death could come at any time, and we should be preparing for our salvation.

Dr. Zucker: [2:34] It’s a reminder that this painting had multiple audiences. It had the Dominican clergy of this church, but there was a secondary audience, the lay people of Florence that were allowed into this part of the church.

Dr. Harris: [2:45] We have to imagine the Dominican friars preaching in front of this image to the citizens of Florence who would come specifically to hear that preaching and people would come to visit their loved ones in the cemetery just outside in the cloister. They’d walk through the door and they would see this image and make a connection between the death of their loved ones and their own mortality.

Dr. Zucker: [3:11] Although this motif was common, almost anybody looking at this painting in the early 15th century would have recognized the changes that Masaccio has brought to this motif, principally the classicism of the architecture and the naturalism of the figures.

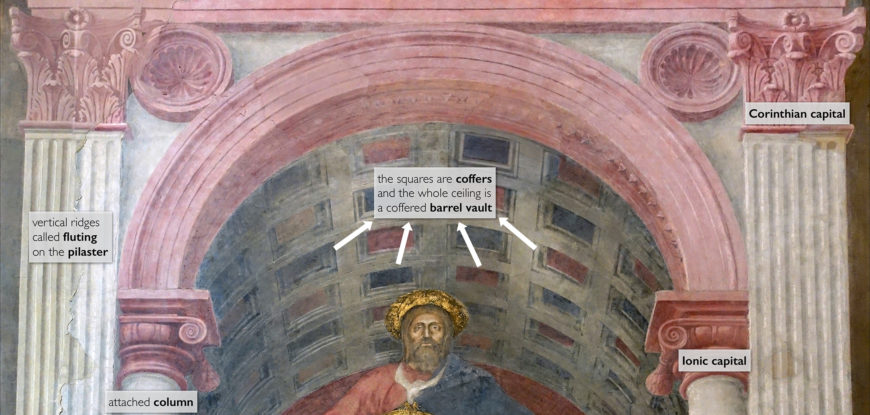

Dr. Harris: [3:26] In most representations of this, Christ and God are placed in a mandorla — that is, a kind of enormous halo that encompassed both figures — and in that way situated them in an otherworldly heavenly space, but here Masaccio has given us what looks like ancient Roman architecture, and in fact, Brunelleschi, the great early Renaissance architect, likely helped design the architectural framework that we see here.

[3:52] On either side, we see fluted pilasters, and those have Corinthian or composite capitals.

Dr. Zucker: [3:59] A pilaster is really a flattened column.

Dr. Harris: [4:01] One that’s attached to a wall.

Dr. Zucker: [4:02] Above that is an entablature and a cornice with dentils, another ancient Roman motif.

Dr. Harris: [4:07] The figures of the Trinity are framed by a round arch, which is a classical arch, not a pointed, medieval Gothic arch, and that arch is carried by two attached columns with Ionic capitals. Everything that we’re describing here is taken directly from ancient Greek and Roman architecture.

Dr. Zucker: [4:27] Behind the arch, we see a barrel vault that’s defined by a beautiful series of coffers with alternating colors, and at the very back of this space, we can see a secondary arch. So we have a very rational space, a measurable space, a space that makes sense.

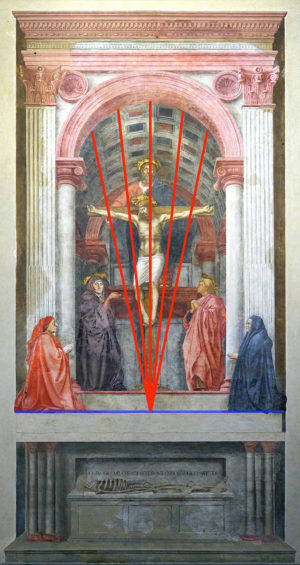

Dr. Harris: [4:42] And it makes sense precisely because Masaccio is using linear perspective. This is one of the earliest uses of linear perspective, rediscovered by Brunelleschi less than a decade before, and Masaccio is using linear perspective to create a convincing illusion that this is not a wall, but in fact the space of a chapel.

Dr. Zucker: [5:04] The linear perspective is made of three components, most importantly a vanishing point, and according to Alberti, who would publish a book called “On Painting” soon after this painting was made, linear perspective works best when the vanishing point is at the eye level of the viewer, and indeed, that is precisely where Masaccio has placed it. It’s in the center of the composition, just a few inches above my eye level.

[5:28] From it radiate a series of orthogonals, illusionistic diagonals that appear to recede in space. They are the agent that create the illusion of depth on a flat surface. Then the third piece is the horizon line, defined by that bottom step.

Dr. Harris: [5:44] Masaccio exploits chiaroscuro, that movement from light to dark, to create a sense of volume. And so we see the rib cage lifted up. We see the muscles in the abdomen, the muscles in the arms. We sense the pull of Christ’s weight from the cross. This interest in naturalistic human anatomy is a key feature of the early Renaissance.

Dr. Zucker: [6:08] Here again is a correspondence with the work of the architect and sculptor Brunelleschi, who produced a wooden crucifix which is also in Santa Maria Novella, which like the painted rendering before us expresses the artist’s careful observation of the human body and understands it responding to gravity, a reminder that Christ here is human, has suffered, has died.

[6:31] Both Brunelleschi and Masaccio could look back a century to another great Italian master, Giotto, and his massive Crucifixion. Here we see perhaps one of the first artists to begin to think about the representation of the human body using light and shadow to define its forms, to begin to pay attention to the anatomy of the body, to render Christ as physical.

Dr. Harris: [6:54] One of the most remarkable things to me is God’s foot. There we have a perfectly foreshortened foot, and therefore, a sense that God is standing. To me, that epitomizes what the Renaissance is about, this interpretation of divine figures as having all of the qualities that human beings have.

Dr. Zucker: [7:15] There’s this wonderful conflict between the visionary and the actual.

Dr. Harris: [7:20] Although the laity couldn’t go beyond the tramezzo, Masaccio is giving the public a taste of what’s beyond by quoting some works of art in the Strozzi Chapel.

Dr. Zucker: [7:31] In that chapel, above the altar, is an image of God, and then just before the chapel and below, there’s a tomb with a fresco of the Lamentation. So there’s a correspondence, perhaps even a deliberate quote, in Masaccio’s painting in the public part of the church.

Dr. Harris: [7:46] What we’re seeing is this very frontal image of God, of the divine, presenting to us the sacrifice that God has made on our behalf. It’s remarkable that this has survived, and we get to see it in its original location.

[8:02] [music]

Left: Masaccio, Holy Trinity, c. 1427, fresco, 667 x 317 cm (Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy); right: Figure annotation of Holy Trinity, Masaccio, Holy Trinity, c. 1427, fresco, 667 x 317 cm (Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy) (photos: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Masaccio was the first painter in the Renaissance to incorporate Brunelleschi’s discovery, linear perspective, in his art. He did this in his fresco, the Holy Trinity, in Santa Maria Novella, in Florence.

Perspective diagram, Masaccio, Holy Trinity, c. 1427, fresco, 667 x 317 cm (Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Have a close look at this perspective diagram. The orthogonals can be seen in the edges of the coffers in the ceiling (look for diagonal lines that appear to recede into the distance). Because Masaccio painted from a low viewpoint, as though we were looking up at Christ, we see the orthogonals in the ceiling, and if we traced all of the orthogonals, we would see that the vanishing point is on the ledge where the donors kneel on.

God’s feet

God’s foot on the right (detail), Holy Trinity, c. 1427, fresco, 667 x 317 cm (Santa Maria Novella, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Our favorite part of this fresco is God’s feet. Actually, you can only really see one of them.

God is standing in this painting. This may not strike you all that much when you first think about it because our idea of God, our picture of God in our mind’s eye—as an old man with a beard—is very much based on Renaissance images of God. So, here Masaccio imagines God as a man. Not a force or power, or something abstract, but as a man. A man who stands—his feet are foreshortened, and he weighs something and is capable of walking. In medieval art, God was often represented by a hand, as though God was an abstract force or power in our lives—but here, he seems so much like a flesh and blood man. This is a good indication of humanism in the Italian renaissance.

Masaccio’s contemporaries were struck by the palpable realism of this fresco, as was Giorgio Vasari, who lived over one hundred years later. Vasari wrote that “the most beautiful thing, apart from the figures, is a barrel-shaped vaulting, drawn in perspective and divided into squares filled with rosettes, which are foreshortened and made to diminish so well that the wall appears to be pierced.” [1]

Architecture (detail), Masaccio, Holy Trinity, c. 1427, fresco, 667 x 317 cm (Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The architecture

One of the other remarkable things about this fresco is the use of the forms of classical architecture (from ancient Greece and Rome). Masaccio borrowed much of what we see from ancient Roman architecture, and may have been helped by the great Renaissance architect Brunelleschi.

Holy Trinity with architectural elements labeled (detail) Masaccio, Holy Trinity, c. 1427, fresco, 667 x 317 cm (Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

- Coffers—the indented squares on the ceiling

- Column—a round, supporting element in architecture. In this fresco by Masaccio, we see an attached column

- Pilasters—a shallow, flattened-out column attached to a wall—it is only decorative, and has no supporting function

- Barrel Vault—vault means ceiling, and a barrel vault is a ceiling in the shape of a round arch

- Ionic and Corinthian Capitals—a capital is the decorated top of a column or pilaster. An ionic capital has a scroll shape (like the ones on the attached columns in the painting), and a Corinthian capital has leaf shapes.

- Fluting—the vertical, indented lines or grooves that decorated the pilasters in the painting—fluting can also be applied to a column