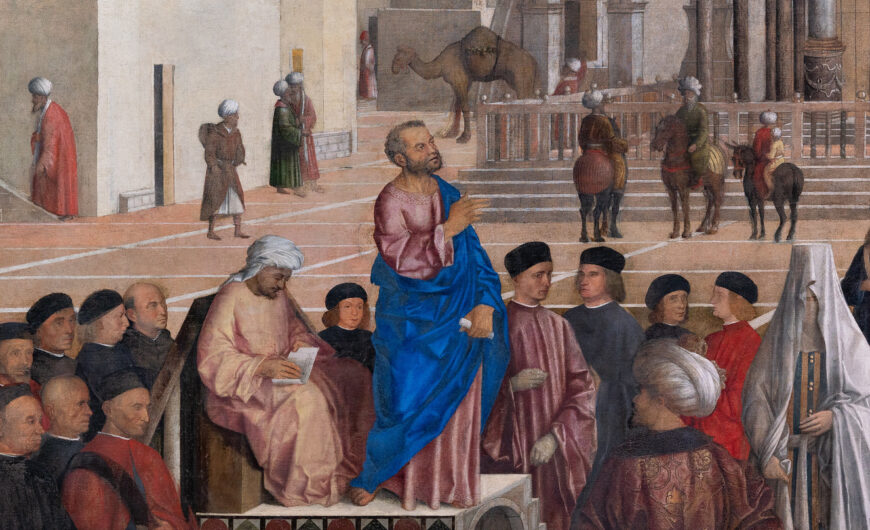

Petrus Christus, A Goldsmith in his Shop, a conversation with Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris in front of Petrus Christus, A Goldsmith in his Shop, 1449, oil on oak panel, 100.1 x 85.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:08] We’re in one of the quietest parts of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This is the Lehman Collection, reconstructed to look like the interior of his apartment, with walls of silk, and furniture, and some real treasures, including a painting that we’re standing in front of, Petrus Christus’s “A Goldsmith in his Shop.”

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:24] When you walk into this room, what you see mostly are religious paintings. And with this painting, we’re looking at something that is secular, although for a long time, we thought it had a religious meaning.

Dr. Zucker: [0:34] It was only a few years ago that a halo was removed from the man seated. That halo was not original but had thrown art historians for some time.

Dr. Harris: [0:43] The other thing that we see in this room are portraits. And in fact, now that this halo has been removed, we can see this painting much more in the light of a portrait than a religious painting.

Dr. Zucker: [1:00] But this is one complicated portrait, because it includes five figures and lots and lots of stuff.

Dr. Harris: [1:06] For a long time, that man in red was thought to be the patron saint of goldsmiths. A saint who was especially associated with the city of Bruges, which is where Petrus Christus painted. An incredibly wealthy city, part of the territories ruled by Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy, who was one of the wealthiest men in Europe.

Dr. Zucker: [1:21] We’re looking in a jeweler’s stall, a small shop that would have opened up onto the street. If you look carefully, you can see a convex mirror that’s reflecting the street beyond us. That is literally what is behind us as we look at this painting.

Dr. Harris: [1:36] It extends the space of the painting so that we join these two figures who are looking into the goldsmith’s stall.

Dr. Zucker: [0:00] But there are already two customers in that stall.

Dr. Harris: [1:50] One of them, the female figure, seems to be gesturing toward the goldsmith, who holds in his hand a balance in which we see a ring. In his right hand he’s holding some weights, as if to balance, to weigh, the amount of gold in the ring.

Dr. Zucker: [2:05] That balance is so delicately held and painted. There’s a long history of representing a balance, of weighing, in the history of art. Generally, it’s Saint Michael at the end of time, weighing the goodness or evil of souls to decide who goes to heaven and who goes to hell.

Dr. Harris: [2:21] Standing next to the scales is a container for the weights and money, gold and silver. Behind the goldsmith, we see not only wares that he’s fashioned that are available, perhaps for sale or to demonstrate the kinds of things he can make, but we also see the raw goods of his trade.

Dr. Steven Zucker: [2:37] I can make out coral, pearls, both seed pearls and larger pearls, what looks like amber. There are fossilized shark teeth. There’s clear crystal and there’s porphyry, all of these exquisite and expensive materials.

Dr. Harris: [0:00] The wealth here is signified, in addition, by the textiles worn by the couple.

Dr. Zucker: [2:57] Especially the woman. She wears this sumptuous outfit that is richly appointed. There’s so much gold in it. Clearly, this is not a common woman.

Dr. Harris: [3:06] If we look at the two figures in the back, their faces seem much more generalized than the figure in the foreground. When conservators have examined the painting, they’ve noted that there is a lot more attention paid to the underdrawing of the seated goldsmith than of the couple in the back. So it’s likely that the figure in the front is a portrait.

[3:33] Now, art historians think that the female figure represents the grandniece of Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy, who just at this time had arranged a marriage for her with the king of Scotland.

[3:46] So she’s about to become the queen of Scotland. Philip the Good, the Duke, sent her off with incredible treasures for her marriage: gold, silver, the most luxurious fabrics. He spent a fortune. And one of the things he did was give her gold and silver objects commissioned from some goldsmiths in Bruges.

Dr. Zucker: [4:13] And so now we’re in the realm of conjecture. We think that this painting might have been commissioned by the goldsmith himself. That is, that this was something that he could have hung up in his guild hall or perhaps even in his shop to show off the fact that he had been patronized by Philip the Good.

[4:25] But it’s important to note that the woman is not a portrait of Philip the Good’s grandniece. That would have been presumptuous to include her in this kind of painting.

Dr. Harris: [4:28] We’re not sure who the male figure is and we’re not sure which goldsmith this is. There were several who furnished items for Philip the Good for his grandniece. The idea is, “I’m a talented and sought-after goldsmith, and I have royal patrons.”

[4:46] There’s possibly another reading here that art historians like to offer, and that is one much more in line with the traditions of the Northern Renaissance, where we tend to see objects from everyday life that also have a religious interpretation, much like the scales we talked about.

Dr. Zucker: [5:02] In the mirror outside, we can see two young men, well-dressed, with a falcon, which is sometimes read as a symbol of pride and greed. And so there’s this contrast that’s being constructed between the outside world, the world where things are less perfect, whereas inside you have this notion of harmony and balance.

[5:22] The other object on the counter in front of us is a belt. Some art historians read that as also associated with matrimony, with the wedding.

Dr. Beth Harris: [5:34] But look at what Petrus Christus can do. He has spent so much effort creating an incredible illusion of reality. The way that sash hangs over this tabletop where we can see the grain of the wood.

[5:47] The way that light glistens on the metal surfaces here, like that gold around the convex mirror. These precise shadows that are cast.

[5:57] Everything is painted with such detail that you get the sense that it was important to the artist and the patron that all of these objects be represented as realistically as possible.

Dr. Zucker: [6:09] There’s an interesting relationship in the north between the representation of jewels and divinity. In so many paintings by Jan van Eyck, for example, God is shown encrusted with jewels. And so, in this more secular context, it’s important to remember that lavish jewelry could be a means with which to represent the divine.

Dr. Harris: [6:30] We know that some of the objects are destined for the church. For example, we see a crystal container, sitting on top of that a pelican, which is a symbol of God’s sacrifice for mankind. This is a container that likely would have held the wafers, the bread, that became the body of Christ during the sacrament of the Eucharist during Mass.

[6:50] Look at how carefully Christus has painted the reflections on those objects, or the wooden shutters that have opened in the window, a kind of attention to everyday facts that’s an important part of Renaissance art.

Dr. Zucker: [7:12] All of this specificity, all of this extraordinarily rich color and texture, is a result of the innovation of oil paint, which Flemish artists had mastered in the 15th century and which we see here brilliantly worked.

[7:19] This is oil paint that allows for the distinction of the stitches of gold in the woman’s dress as opposed to the clarity of the mirror or the cracks that we can see in the mirror. It allows for the softness of the velvets versus the slippery, hard quality of the coral. It is literally oil that makes this painting possible.

[0:00] [music]

Petrus Christus, A Goldsmith in his Shop, 1449, oil on oak panel, 100.1 x 85.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Out shopping

Goldsmith in his Shop reveals its complexities to the viewer over time. At first, one sees a group of three people inside a room filled with trinkets. The two standing figures—a male and a female in dressed in rich, expensive-looking clothing—appear to be a couple, as the man has his arm wrapped around the back of the woman. This woman gestures with her left hand towards the seated man, who, clad in a plain, red garment with a matching hat, looks up at the woman. In his left hand, he holds a small balance which supports a gold ring (fans of northern art will recognize this as a small scale—much like the one that appears in Vermeer’s much later Woman Weighing Gold from 1662-1663). In fact, the figures are inside a gold shop, and the man is a goldsmith. The baubles on display—objects made from precious metal, stones, glass, and coral—are his wares, and the standing couple is probably about to make a purchase.

Left: Mirror, Jan Van Eyck, Arnolfini Portrait, 1434 (detail); right: Mirror and still-life (detail), Petrus Christus, A Goldsmith in his Shop, 1449 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

However, there is much more to this story. The smith appears to be seated at a work desk, but in fact, the front of the desk is visible, and a length of fabric hangs over it, into our space. Most importantly, a convex mirror resting on the smith’s desk (in the lower right hand corner of the painting) reveals a cityscape. What we see is not a mere desk however. It is, in fact, the front of the smith’s shop, which opens on a street in Bruges (in present-day Belgium, and the city where Christus lived and worked). The two young men captured in the mirror hold a falcon and approach the smith’s shop. The mirror situates us, the viewer, on the street in Bruges with that couple, looking into the smith’s shop at the artisan and the rich patrons behind him.

A gift for a royal wedding

Although genre scenes, or images of every day life, became popular in the North later (“the North” meaning all of the countries above Italy), Christus’ creation of illusionistic and complex space implies that the painting also carries a complex meaning. Since the painting is signed and dated by the artist in white paint in the center foreground, it can firmly be placed in the year 1449. This is the year that King James II of Scotland married Mary of Guelders. The duke of Burgundy, Phillip the Good, who was also a renowned patron of the arts in Bruges, commissioned the goldsmith Willem van Bleuten to make the couple a gift for their wedding. Thus, the painting is believed to depict van Bleuten as he is about to give the royal couple a gift of golden rings, made for their marriage.

This interpretation also explains the very expensive brocaded and bejeweled clothes—well out of the budget of the average man—worn by the standing couple. The piece of fabric on the desk is believed to be a wedding girdle (belt), and also supports this interpretation.

The two men in the convex mirror may not only be a device used to demonstrate the artist’s virtuoso skill in this tour de force of illusionistic painting. The falcon held by the men is a symbol of greed and pride. Since the scale in the hand of the goldsmith, along with the illusions to marriage and purity, represent perfection and balance, the presence of the two figures with their ill-associated bird creates a contrast between the perfect world of the royals and the imperfect world of the viewer. The royal couple is morally superior to the common man.

Couple (detail), Petrus Christus, A Goldsmith in his Shop, 1449, oil on oak panel, 100.1 x 85.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Petrus Christus’ artistic concerns are typical of painters of his time. The minute detail of the trinkets in the shop, as well as the luminosity of the painting, are only possible because of the use of oil paint, which was not common in Italy until many years later (indeed, the technique is commonly believed to have come to Italy from the North). The use of convex mirrors was a device exploited by northern painters, such as in Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434)—another oil on oak panel painting. In that painting, a convex mirror hanging in the back of the room reflects the artist himself, whose self-portrait con be discerned in the glass. In Christus’s painting, the round surfaces of the jewels and goblets echo the convex mirror, and the white highlights that are used to create both light and volume betray an interest in still-life painting which would come to dominate northern painting hundreds of years later.

Still life and Mirror (detail), Petrus Christus, A Goldsmith in his Shop, 1449, oil on oak panel, 100.1 x 85.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Although northern art of this period is often compared to Italian art (and often unfavorably at that), paintings such as Petrus Christus’ Goldsmith in his Shop demonstrate that, although the concerns of the northern artist were different, they were no less talented, their paintings no less beautiful and complex. Indeed, northern paintings from this period (by Petrus Christus himself, along with his contemporaries Jan van Eyck and Hans Memling) were often bought by Italians and made their way into Italy and helped shape the style of the Italian High Renaissance, as well as the Mannerist period that followed. Still, these paintings deserve to be appreciated in their own right as examples of the rapid artistic changes that occurred in the early 1400s, as the world was on the precipice of great political, historic, and cultural revolutions that would end the Middle Ages and bring us into the Modern World