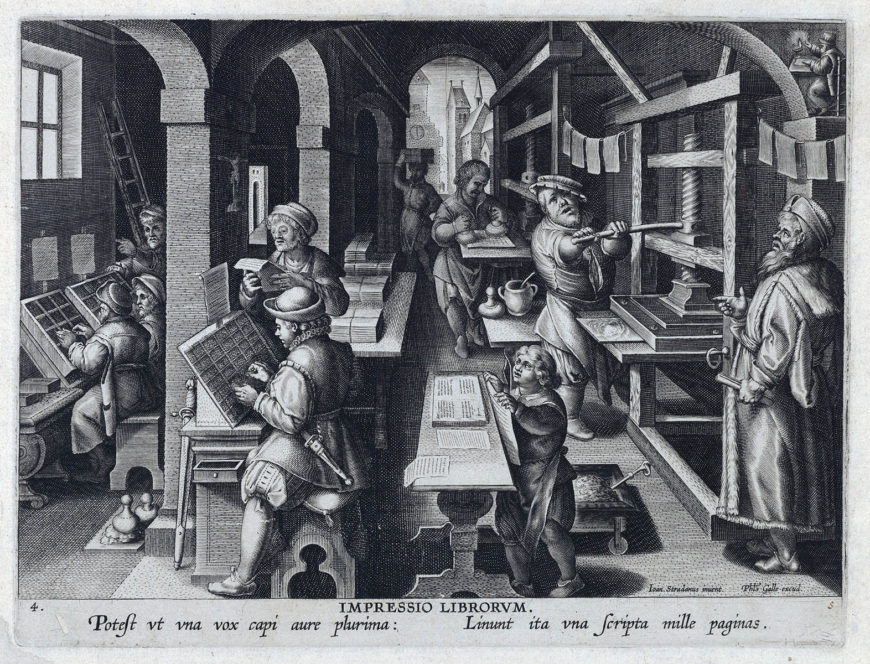

Book printing was a collaborative effort, as we see here with different people preparing a book for the printing press. Jan Collaert I after Joannes Stradanus, “The Invention of Book Printing,” in New Inventions of Modern Times (Nova Reperta), plate 4, c. 1600, engraving on paper, 27 x 20 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The printing press was arguably one of the most revolutionary inventions in the history of the early modern world. While the fifteenth-century German goldsmith and publisher, Johannes Gutenberg, is heralded for his creation of a mechanical printing press that allowed for the mass-production of images and texts, the technology of movable type was first pioneered much earlier in East Asia. In early eleventh-century China, the artisan Bi Sheng discovered that he could make individual Chinese characters from baked clay to create a system of movable type. Later, in thirteenth-century Korea, the first known metal movable type was produced.

Pages from the world’s oldest extant book printed with movable metal type, Anthology of Great Buddhist Priests’ Zen Teachings, 1377, 24. 5 x 17 cm (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Increased contact and exchange between cultures in East Asia and Europe by way of the Silk Roads, starting in the thirteenth century, led to the spread of such printing innovations. Indeed, by the mid-1400s, Gutenberg was in a prime position to devise his mechanical process for printing multiples of the same textual sources and visual representations, which, thanks to the portable and more affordable paper support, meant they could be circulated widely, serving as an early mode of mass communication in the pre-digital age. The publication of prints coupled with the introduction of movable type offered unprecedented possibilities for the cross-cultural exchange of knowledge and ideas, as well as artistic styles and designs.

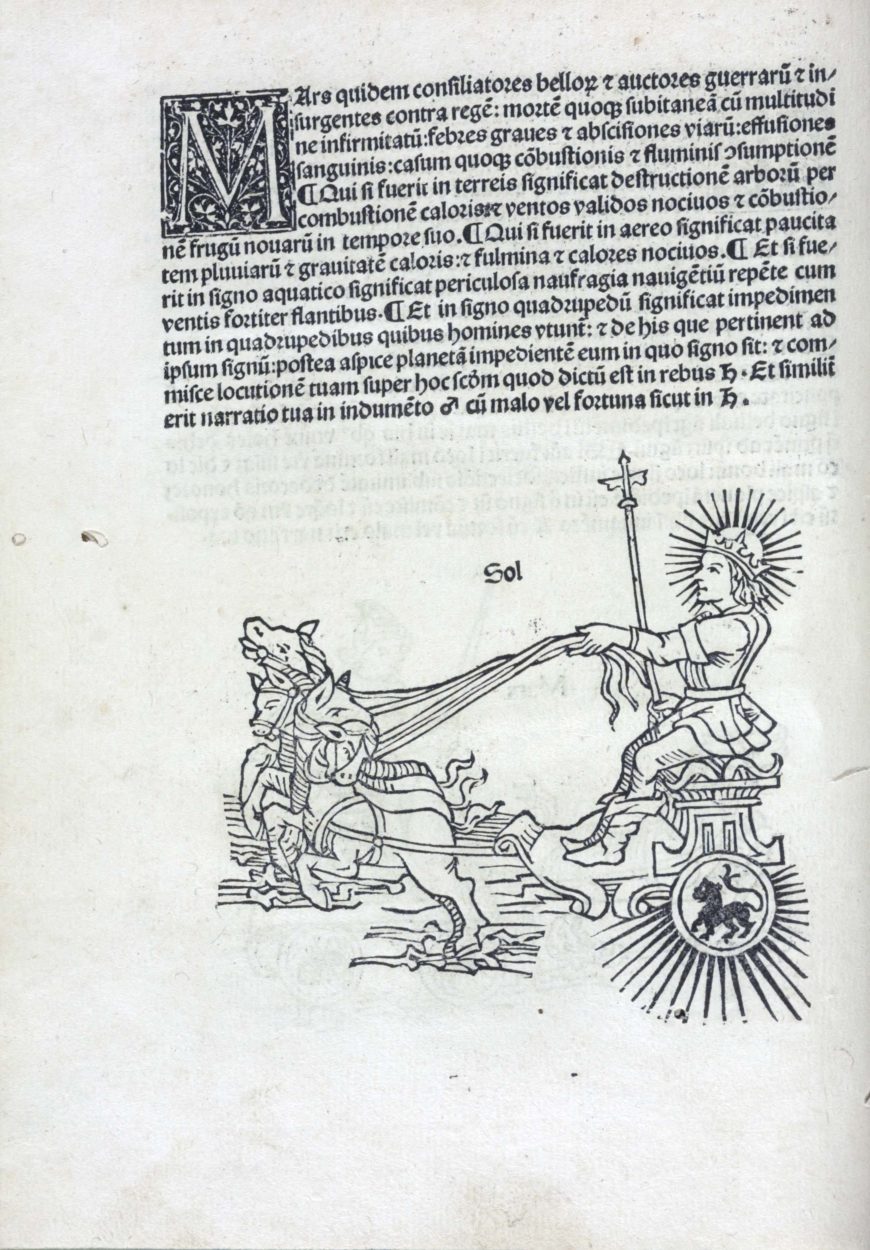

This illustration comes from a book published by Erhard Ratdolt, an early German printer from Augsburg, and is illustrated with seventy-three woodcuts. Here we see “Sol” or “Sun,” in Albumasar, Flores astrologiae (Augsburg: Erhard Ratdolt, November 18, 1488), image 22 (Rosenwald Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress)

The democratization of art

Prior to the fifteenth century, works of art like altarpieces, portraits, and other luxury items were primarily found in the residences of wealthy patrons and in churches because it was the social elite and religious leaders in the community who had the financial resources to commission these exquisite objects. The reproducible format of print and the increasing availability of paper afforded the growing middle class, who may have not had the means to purchase paintings or statues, the opportunity to collect artistic representations. While large-scale projects were still funded by affluent patrons, the majority of prints were bought on speculation. As a result, we see a range of subject matter depicted in print that would have appealed to diverse collectors. For instance, the desire to study the past, literature, and science in cities across early modern Europe encouraged printmakers to supply the art market with representations of ancient history, classical mythology, and the natural world.

Diamond Sutra, 868, woodblock-printed scroll, found in the Mogao (or “Peerless”) Caves or the “Caves of a Thousand Buddhas,” which was a major Buddhist center from the 4th to 14th centuries along the Silk Road (British Library)

Woodcut

The oldest form of printmaking is the woodcut. As early as the Tang Dynasty (beginning in the seventh century) in China, woodblocks were used for printing text onto pieces of textile, and later paper. By the eighth century, woodblock printing had taken hold in Korea and Japan. Although the practice of printing written sources is part of a much older tradition in East Asia, the production of printed imagery using woodblocks was a more common phenomenon in Europe, starting in late fourteenth-century Germany and subsequently spreading to the Netherlands and south of the Swiss Alps to areas of northern Italy.

Early woodcuts often show religious subject matter. Here we see the Virgin Mary cradling her dead son, Jesus. Southern Germany, Swabia, Pietà, c. 1460, woodcut, hand colored with watercolor, 38.7 x 28.8 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland)

Petrus Christus, Portrait of a female donor kneeling before a book with a print hanging on the wall behind her (detail), c. 1455, oil on panel, 41.8 x 21.6 cm (National Gallery of Art)

During the second half of the fifteenth century after Gutenberg invented his printing press, woodcuts became the most effective method of illustrating texts made with movable type. As a result, cities in Europe—namely Mainz, Germany and Venice, Italy—where printmaking initially took hold developed into important centers for book production. The European method of making printed images on paper using a mechanical press made its way to East Asia by the sixteenth century, but it was not widely adopted for artistic purposes until a couple centuries later during the Edo period in Japan when colored woodcuts (ukiyo-e prints) were produced in great numbers.

The earliest European loose-sheet woodcuts depict predominately Christian subjects, serving as relatively inexpensive devotional images. While museums today preserve prints in climate-controlled boxes to ensure that they last for future generations to enjoy, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, they were folded up and carried by pilgrims on their travels, cut and pasted into the interior covers of books, or tacked up onto walls of a home. Consequently, few early woodcuts survive because they were often destroyed through continual use. Yet, key extant woodcuts reveal the stylistic character of this early type of print.

This woodcut survived a fire. It shows Mary holding the infant Jesus, surrounded by saints and scenes from the life of Mary. Unknown 15th–century printmaker, Madonna of the Fire, before 1428, woodcut, hand colored with paint, dimensions unknown (Cathedral of Santa Croce, Forlì, Italy)

For example, two woodcuts (the Pietà made in southern Germany and the early fifteenth-century Italian Madonna of the Fire that allegedly survived a fire that destroyed the building in which it was housed) both exhibit figures and other scenic elements that are rendered with thick outlines. These images feature minimal shading and patterning, resembling stenciled designs to which a collector often applied paint by hand to enhance the emotional appeal of the composition. This is seen with the incorporation of red streaks of paint that represent blood dripping from Christ’s wounds in the Pietà print.

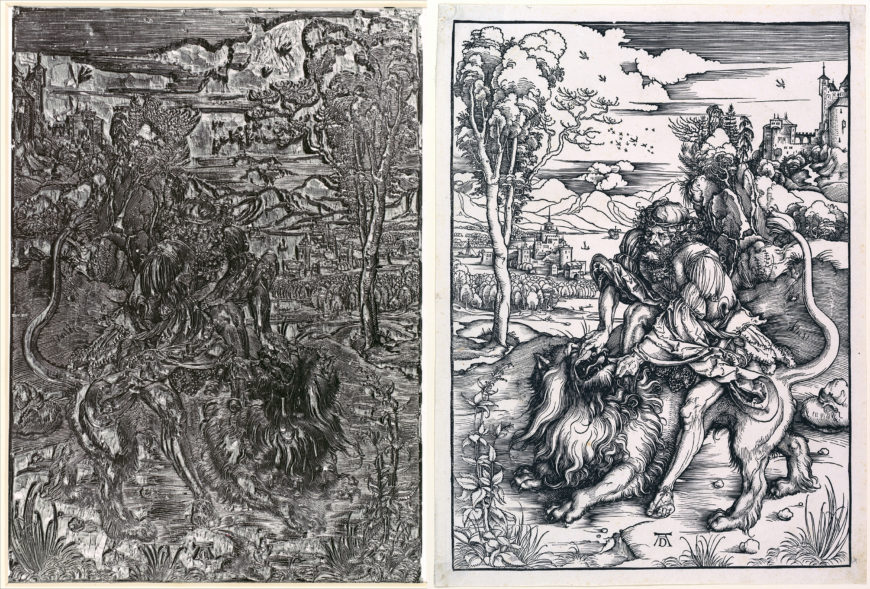

Left: Albrecht Dürer, woodblock for Samson and the Lion, c. 1497−1498, pear wood, 39.1 x 27.9 x 2.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); right: Albrecht Dürer, Samson and the Lion, c. 1497−1498, woodcut, 40.6 x 30.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A contemporary artist uses a handheld gouger to cut a woodcut design into Japanese plywood. The design has been sketched in chalk on a painted face of the plywood (photo: Zephyris, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A type of relief process, a woodcut is produced by inking the raised surface of the matrix, which will result in a mirror impression of the composition when the block is pressed onto a sheet of paper using manual or mechanical (a printing press) pressure. The rubber stamp is a modern example of relief printing. To create the design on the block of wood, an artist uses a knife or gouge to cut away sections of the wood in between the lines and shapes that are to be printed. When cutting out the areas of wood, one has to be careful not to make the raised lines too thin or else they may break when pressure is added to produce an impression, which is why early woodcuts feature designs with bold contours.

The relief process is one of the main types of printmaking. To make a woodcut, an artist inks the raised surface of the matrix, which creates a mirror impression of the composition when the block is pressed onto a sheet of paper using manual or mechanical (a printing press) pressure (video from The Museum of Modern Art).

By the late fifteenth century, the German artist Albrecht Dürer found a way to portray impressive textural and tonal subtleties in his prints. By carving a series of thin lines close together in his Samson and the Lion, he convincingly represented shadows on the hillside.

The white areas in this print are uninked, acting as highlights in the scene. Lucas Cranach the Elder, Saint Christopher, c. 1509, chiaroscuro woodcut (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland)

Chiaroscuro woodcut

As indicated by the production of hand-colored woodcuts like the Pietà and Madonna of the Fire, some collectors preferred the aesthetic and emotional intrigue of colored prints. In the sixteenth century, printmakers in northern Europe and Italy capitalized on that interest by making colored woodblock prints known as chiaroscuro woodcuts because they imitate the appearance of chiaroscuro drawings. In this type of drawing, the colored paper serves as the middle tone to which an artist adds white pigment to produce light (chiaro) tones and renders darker (scuro) values by incorporating hatch marks with a pen or areas of dark wash with a brush. The same concept applies to chiaroscuro woodcuts. Lucas Cranach’s Saint Christopher, for example, was made with two different woodblocks. One woodblock, referred to as the tone block, created the orange mid-tone. The second woodblock, called the line block, produced the black lines, that is the base design and hatching. The unprinted areas of the paper act as highlights.

An example of niello plaques, with incised linear designs on a metal surface which were inlaid with a dark paste-like substance. Devotional Diptych with the Nativity and Adoration, c. 1500, Paris, France, silver, niello, gilt copper alloy, 13.9 x 20.8 x 0.7 cm (The Cloisters Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Engraving

Not long after the first woodcuts were made, the intaglio process of engraving emerged in Germany in the 1430s and was used throughout other areas of northern and southern Europe by the second half of the fifteenth century (intaglio is a category of printmaking that includes engraving, drypoint and etching). Engraving remained a common method for printmaking through the end of the eighteenth century until the invention of planographic techniques like lithography. Engraving has its roots in the tradition of gold- and silversmith workshops where niello plaques—small plates of gold or silver—were made by incising a linear design into the metal surface and inlaying those carved grooves with a dark paste-like substance to render a clear representation.

Artists scratched and etched metal plates to create fine surface detail (video from The Museum of Modern Art).

Burins used in the engraving process (photo: Manfred Brückels, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Unlike the relief process of woodcut, an engraving is produced by sculpting into a copper plate using a tool with a lozenge-shaped tip called a burin, which leaves behind a V-shaped groove. Once the design has been fully incised, the entire surface of the plate is inked. Next, the plate will be wiped clean so that only the ink deposited into the incised lines will remain. Now the matrix is ready to be run through the printing press with a damp sheet of paper. The pressure from the press pushes the paper into those grooves and picks up the ink, resulting in a mirror impression of the image engraved on the copper plate.

Even though this is one of Schongauer’s earliest engravings, it was wildly influential. Michelangelo even copied it. Martin Schongauer, Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons, c. 1475, engraving, 30.0 x 21.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In comparison to the difficulty of carving a relief design into a woodblock, the technique of engraving allowed skilled artists to create magnificently detailed and stylistically varied compositions without the fear of producing too narrow of lines that would break under the pressure of a mechanical press. One of the greatest engravers in renaissance Europe was Martin Schongauer. His St. Anthony Tormented by Demons shows off his versatile engraving technique.

Martin Schongauer, details of Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons, c. 1475, engraving, 30.0 x 21.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

To produce different textures, Schongauer used a variety of marks, such as long, curling lines to render the soft fur on the demon brandishing a club short U-shaped lines to create the scales of the creature grabbing Anthony’s left arm. By incorporating passages of dense cross-hatching across Anthony’s body, Schongauer also gave his figure a three-dimensional presence on the flat paper surface.

Etching likely developed in the workshop of Daniel Hopfer, who created ornamental designs in the surface of metal armor. Attributed to Kolman Helmschmid, etching attributed to Daniel Hopfer, Cuirass and Tassets (Torso and Hip Defense), with detail of Virgin and Child on the center of the breastplate, c. 1510–20, steel, leather, 105.4 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Etching

Another intaglio process that developed in Germany around 1500 and remained popular throughout the early modern period was etching. While engraving originated from the craft of gold- and silversmithing, etching was closely related to the armorer’s trade. Etching likely developed in the workshop of Daniel Hopfer in Augsburg, a city in southern Germany. Hopfer discovered that through etching he was able to create ornamental designs in the surface of metal armor.

To etch an iron or copper printing plate, an acid-resistant substance (usually a varnish or wax) called a ground is applied to its surface. With a stylus or needle an artist draws a design into the ground, removing some of the coating each time a mark is made. After the design is complete, the plate is submerged into an acid bath and a chemical reaction takes place. The acid bites into the exposed metal, creating linear grooves. Once the plate is taken out of the bath and the ground is removed, the incised matrix is ready to be inked and printed in the same way as an engraving. Whereas engraving takes considerable manual labor because the printmaker has to carve into the metal plate, in the etching process, the acid does all of that work, and so it was considered an easier alternative to engraving. Artists who were adept at drawing, but not necessarily trained to engrave plates, found etching to be a suitable medium to make prints, since realizing a design in the ground with a needle was akin to drawing with a pen on paper.

Parmigianino, Entombment, 1529−1530, etching, 27.1 x 20.4 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland)

Just like engraving, which had originated in Germany but quickly became popular among artists in other parts of Europe like Italy, etching also spread throughout the continent soon after its development. Parmigianino was one early sixteenth-century Italian painter and draftsman who tried his hand at etching. His Entombment shows off his expressive line work. It appears “sketch-like,” resembling a pen-and-ink drawing rather than an engraving, which is usually characterized by regularized lines and marks of equidistant spacing and length.

First state, Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Presented to the People, 1655, drypoint i/viii, 38.3 x 45.1 cm (British Museum, London)

Drypoint

Drypoint is perhaps the simplest method for creating an intaglio print. It developed at the same time as engraving in early fifteenth-century Germany, and like other related processes, drypoint attracted printmakers working across Europe. The technique involves using a stylus or needle to scratch into the surface of the copper matrix to throw up a burr. Just as the sides of a furrow or trench dug into the ground will hold drifts of snow, the raised edges of a drypoint line will retain ink. When making an engraving, the printmaker scrapes away the burr in order to achieve clean lines when the plate is printed. In a drypoint, however, the burr is left so that when the plate is printed, it produces a rich, velvety line. Unlike engraving, which can yield hundreds of decent impressions, the delicate drypoint burr wears quickly each time a plate is run through the press. For this reason, drypoint was most often used to add finishing touches to compositions after the primary design had been engraved or etched. Yet, some printmakers like the seventeenth-century Dutch master, Rembrandt, preferred to work entirely in this technique.

Detail, first state, Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Presented to the People, 1655, drypoint i/viii, 38.3 x 45.1 cm (British Museum, London)

In Christ Presented to the People, the contours of Pontius Pilate, Christ, and the surrounding soldiers reveal the dense, blurred character of the drypoint burr. Because drypoint created few quality impressions, Rembrandt often reworked his plates, making different states of the same image in order to produce more legible representations. The first state was printed early on in the plate’s lifetime before the burr began to wear. In the fourth state, the once-strong velvety lines have all but disappeared and changes to the architecture are visible. Most noticeably, the balustrade depicted near the upper right does not appear in the first state.

Fourth state, Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Presented to the People, 1655, drypoint iv/viii, 35.8 x 45.4 cm (British Museum, London)

Mezzotint

Mezzotint rockers (photo: Toni Pecoraro)

The term mezzotint is a compound of the Italian words mezzo (“half”) and tinta (“tone”), and describes a type of intaglio print made through gradations of light and shade rather than line. To produce a mezzotint, an artist roughens the entire surface of a copper plate with a tool called a “rocker,” a chisel-like implement with a semi-circular serrated edge. This tool is rocked back and forth across the plate until it has been completely worked, creating a surface full of burr that will hold ink. If you were to print an impression at this stage, it would appear as a field of rich black. To create a legible image, the printmaker must work from darkness to light with the aid of a scraper—a triangular-shaped blade fixed in a knife handle—and a burnisher—a blunt instrument with a hard, rounded end. By removing or smoothing out the burr, the artist weakens the plate’s capability to hold ink when the plate is wiped, and those areas will print a lighter tone.

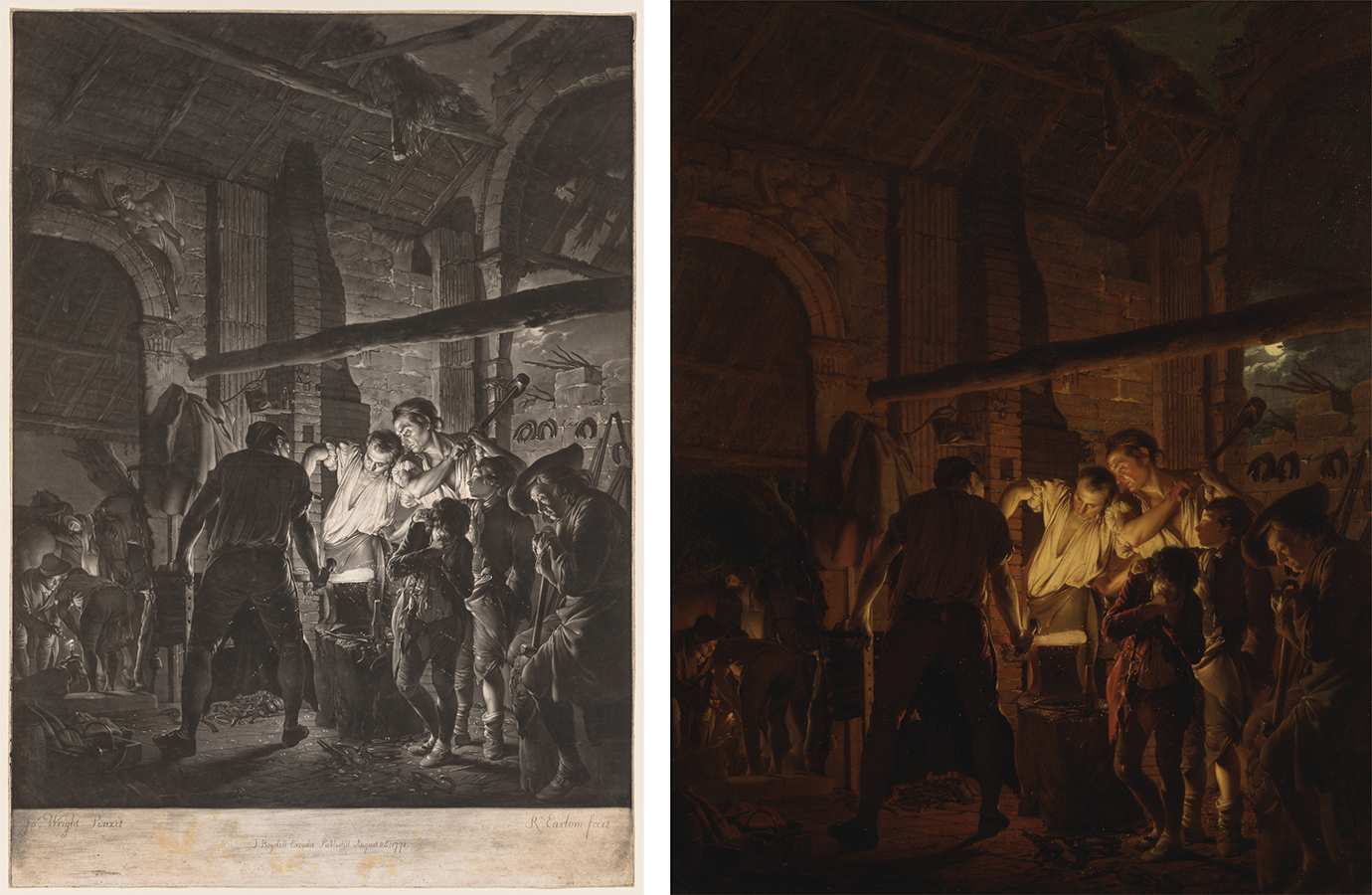

Left: Richard Earlom after Joseph Wright of Derby, The Blacksmith Shop, 1771, mezzotint ii/ii (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland); right: Joseph Wright of Derby, The Blacksmith Shop, 1771, oil on canvas, 128.3 x 104.1 cm (Yale Center for British Art, New Haven)

Although mezzotint originated in Amsterdam during the second quarter of the seventeenth century, it found particular appeal in eighteenth-century London, so much so that the medium was even nicknamed “the English manner.” When the Dutch-born sovereign William III became King of England in the late 1600s, numerous printmakers from the northern provinces of the Netherlands relocated to London in hopes of achieving royal patronage. During successive decades, native English artists learned from their Dutch contemporaries about how to make mezzotints and several technical manuals on the subject were also published locally. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, England had earned the reputation as a prolific center for mezzotint production. Richard Earlom was one English printmaker who had a successful career making mezzotint reproductions of oil paintings. The Blacksmith Shop from 1771 is based on Joseph Wright of Derby’s painting of the same subject. Wright’s pictures, which exhibit dramatic lighting effects, were ideally suited to be translated into mezzotint because the medium could capture the subtle tonal variations and lustrous appearance of his oil paintings.

Aquatint

Aquatint is a variant of the etching process that produces broad areas of tone that resemble the visual effects of watercolor. It involves the use of a powdered resin that is adhered to the plate through controlled heating. As the resin bonds to the plate, it creates a network of linear channels of exposed metal (think of how a cake of mud that is dried in the sun has a web of cracks). Once the plate is bitten by acid, the areas of exposed metal form deep grooves that are capable of holding ink.

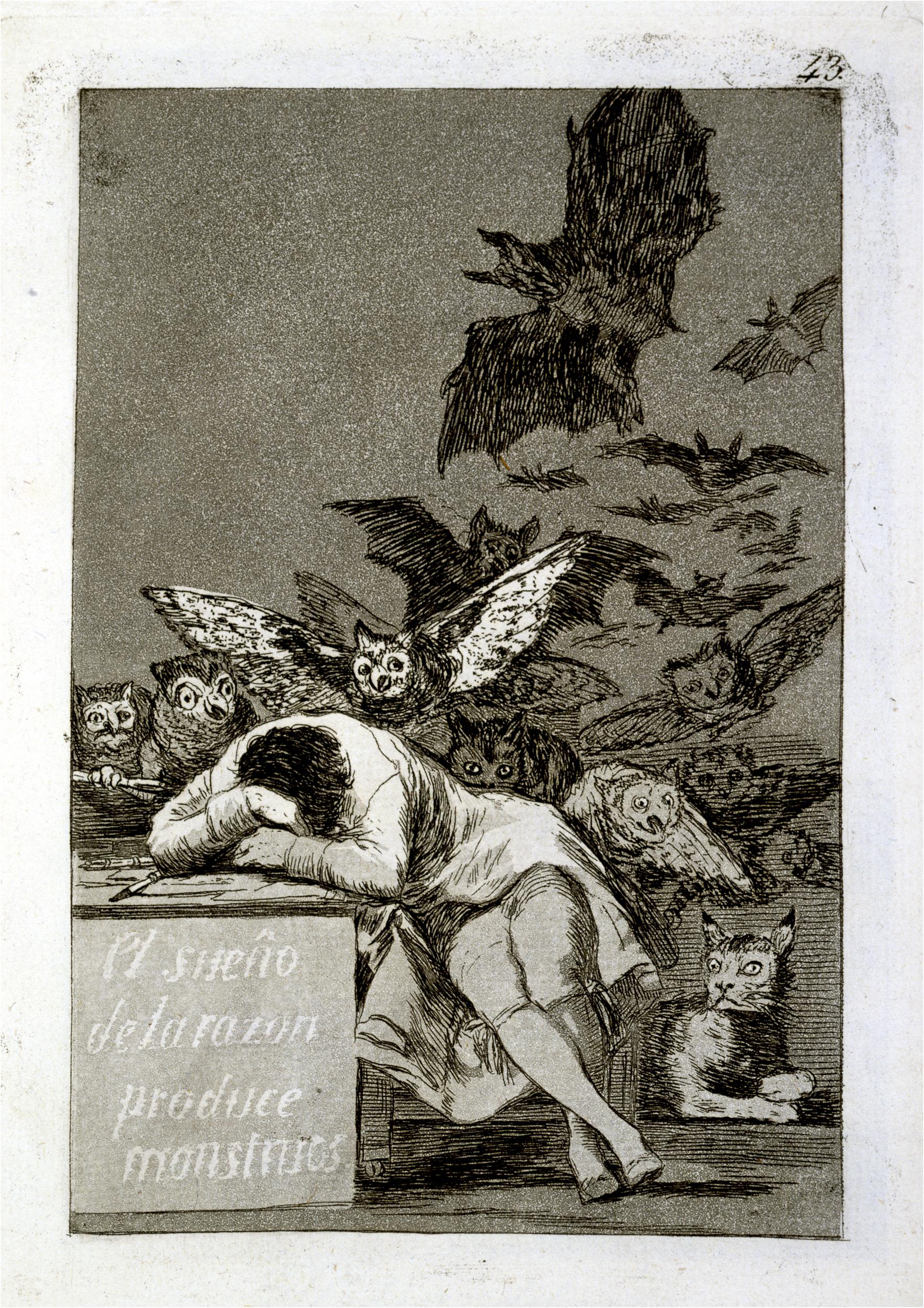

Francisco de Goya is famous for his artworks using aquatint. Goya, Los Caprichos: The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, 1799, etching and aquatint, 21.2 x 15.0 cm (British Museum, London)

Aquatint was first introduced in the mid-seventeenth century in Amsterdam. Yet, unlike other printmaking techniques that found immediate attraction, it would take some time before aquatint became more widely used. By the late eighteenth century, several English etchers had become drawn to the more painterly qualities of aquatint, but the medium arguably achieved its greatest acclaim under the Spanish artist, Francisco de Goya. To make The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, Goya first etched his sleeping artist, the bats, and haunting cat with quick lines. From there, he switched to aquatint to render the ominous shadow that envelops the entire composition and the white letters on the front of the artist’s desk.

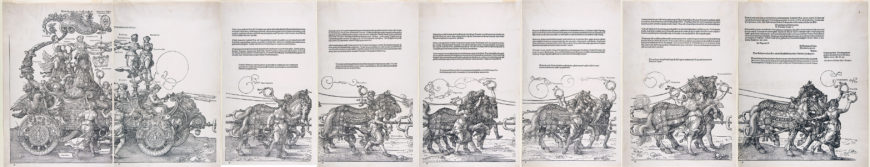

An example of a multi-sheet composition. Albrecht Dürer, Large Triumphal Carriage, c. 1518−1522, woodcut (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

The business of printmaking

Printmaking in early modern Europe was a complex enterprise that involved a number of different agents. It was not always the case that the individual responsible for carving the woodblock or incising the metal plate was the designer of the composition. When Dürer was commissioned by Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I to design a complex, multi-sheet composition of the, he teamed up with a talented workshop of block carvers to help him execute that grand-scale project. In some workshops, the figure who undertook the physical process of printing the blocks and plates may have only done that job. Additionally, there may have been a separate position dedicated to print publishing, that is selling and distributing the prints. Depending on the size of a workshop and the equipment available, some printmakers or publishers had to contract out some of those tasks. For example, if a publishing shop did not own a press, it had to collaborate with another local shop to produce its prints. Early printmaking revolved around a sophisticated network of artists and businessmen, and this legacy is still seen today. Many contemporary printmakers partner with a printing shop to create their work and/or a commercial gallery to exhibit and sell their art.

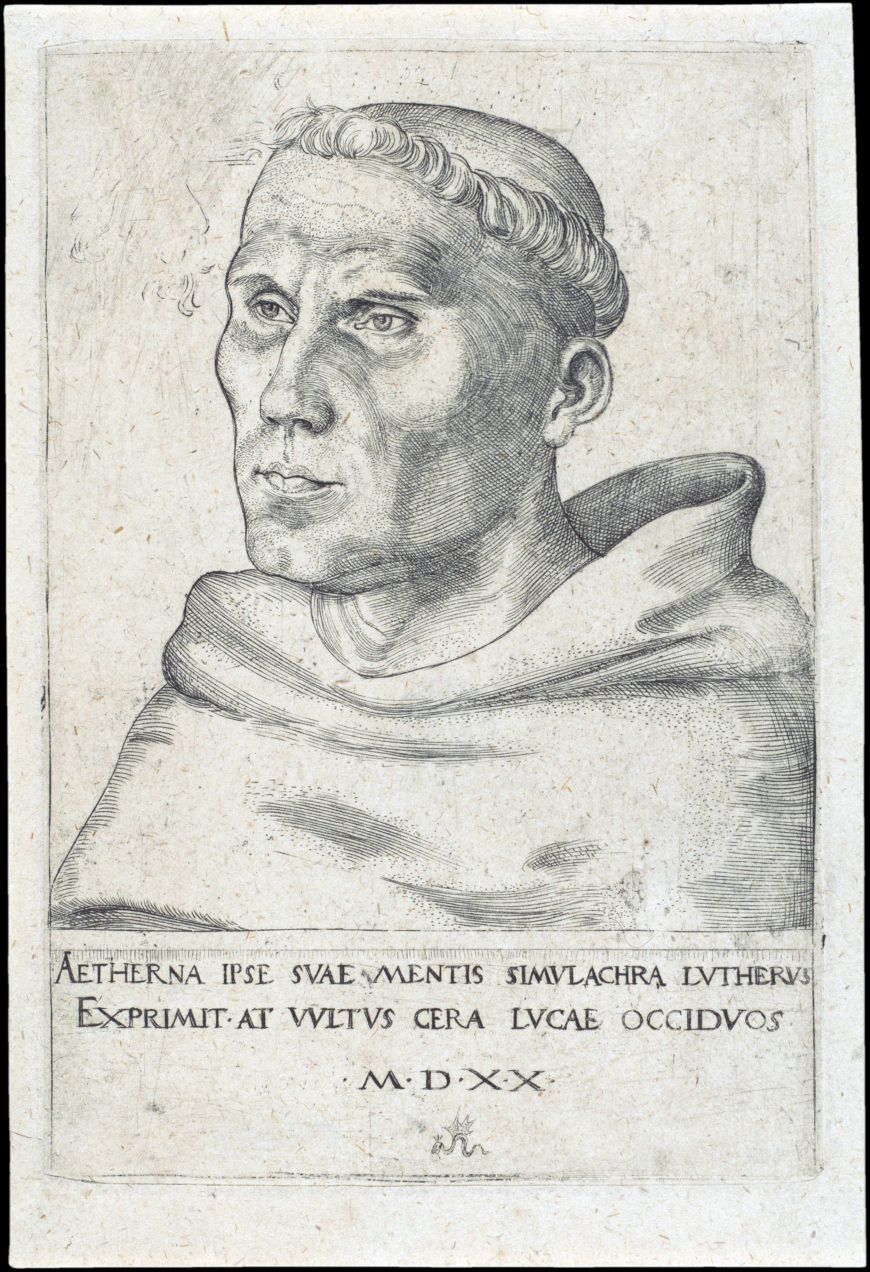

Martin Luther was an Augustinian monk and professor of theology in Wittenberg. He posted his 95 Theses on the door of the castle church in Wittenberg—at least, this is how the tradition tells the story—that took issue with the way in which the Catholic Church thought about salvation, and it specifically took issue with the selling of indulgences. Lucas Cranach the Elder, Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk, 1520, engraving, 15.8 x 10.7 cm (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The advent of print not only transformed how images were made, but it created new possibilities for art collecting and mass communication. Scholars have long recognized how the mass distribution of printed pamphlets criticizing the Roman Church’s sale of indulgences and the pope’s supremacy along with printed portraits of Martin Luther, such as Cranach’s Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk, spurred on a religious revolution in northern Europe by promoting the agenda of Protestant Reformers.

![Books made in early colonial Mexico often stressed the importance of images in the process of converting Indigenous peoples. Juan Bautista, Confessionario en lengua mexicana y castellan [Preparation of the penitents in Nahuatl and Spanish] (Santiago Tlatelolco: Melchor Ocharte, 1599), 1v–2r.](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/confessionario-mexico-870x689.jpg)

Books made in early colonial Mexico often stressed the importance of images in the process of converting Indigenous peoples. Juan Bautista, Confessionario en lengua mexicana y castellana [Preparation of the penitents in Nahuatl and Spanish] (Santiago Tlatelolco: Melchor Ocharte, 1599), 1v–2r (John Carter Brown Library)