Raffaello Sanzio, better known simply as Raphael, enjoyed a meteoric career. An impeccable professional artist and a consummate courtier, Raphael was famed both for his artistic skill and his charismatic personality. From his beginnings as a local painter in his native Marche and later Florence, Raphael skyrocketed to fame in Rome, ultimately becoming the city’s most sought-after artist. Raphael’s untimely death at the age of 37 (in 1520) while at the height of his visual powers only solidified the legend of his extraordinary talent.

His visual accomplishments range from paintings of all sizes and drawings in chalk and ink—some intended to be translated to print—to elaborate fresco cycles, tapestry designs, and architecture. He was shrewd and meticulous, and his work is notable for its elegance and poise, for the ease with which he translated nature into idealized artifice. How does one paint divine grace or the very concept of philosophy? Raphael did such things with apparent ease. He embodied the ideal of sprezzatura (the appearance of nonchalant effortlessness in his creative process), a notion popularized by Raphael’s good friend, Baldassare Castiglione, in his Book of the Courtier (1528).

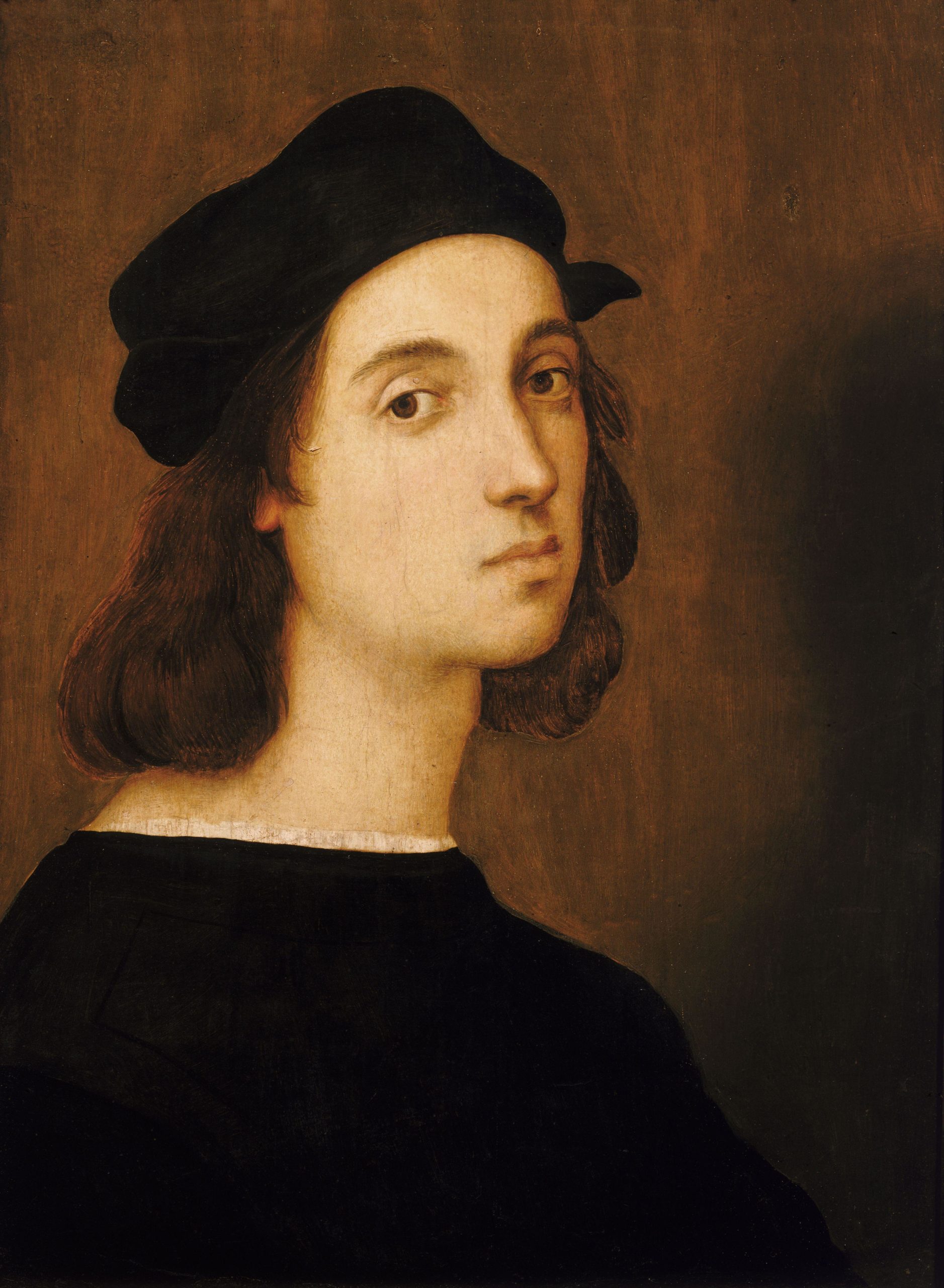

![Portrait of Raphael, from Giorgio Vasari, Le Vite De' Piu Eccellenti Pittori, Scultori, E Architettori, 1791 [1568]](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Rafael-Vasari-300x370.jpeg)

Portrait of Raphael, from Giorgio Vasari, Le Vite De’ Piu Eccellenti Pittori, Scultori, E Architettori, 1791 [1568]

How do we know about him?

“For in truth we have from him art, colouring, and invention harmonized and brought to such a pitch of perfection as could scarcely be hoped for; nor may any intellect ever think to surpass him. And in addition to this benefit that he conferred on art, like a true friend to her, as long as he lived he never ceased to show how one could deal with great men, with those of middle station, and with the lowest.” Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects [1]

Information about Raphael’s life comes from relatively few surviving contemporary documents that refer to him, and two biographies written in the sixteenth century. Paolo Giovio, who knew Raphael personally, wrote an essay on the artist’s life shortly after his death in 1520. In 1550, Giorgio Vasari wrote an extended biography of Raphael for his Lives of the Artists, published in 1550 (expanded in 1568). Despite Raphael’s very public career, we have scant evidence of his personal life, private correspondence, and other writings to reveal the man behind the public persona.

Early career

Raphael was born in Urbino into the circle of one of the most sophisticated and intellectually oriented courts in Italy. Following the tradition of family craft, Raphael was initially trained by his father, Giovanni Sanzio, who was court painter to the ruling Montefeltro family and ran a thriving workshop. Vasari tells us that Raphael was sent by his father to continue his training under Pietro Perugino, presumably because the precocious youth had learned all he could at home. Perugino was a leading artist in both Florence and his native Perugia and his influence on Raphael’s early paintings is unmistakable. Recent scholarship however, suggests that Raphael’s associations with Perugino came a bit later, his early training continuing in the family workshop even after his father’s death in 1494.

Left: Perugino, Marriage of the Virgin, 1500–1504, oil on wood, 234 x 185 cm (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen); right: Raphael, Marriage of the Virgin, 1504, oil on panel, 174 × 121 cm / 69 × 48″ (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan)

An altarpiece depicting the Marriage of the Virgin (1504) shows Raphael’s indebtedness to Perugino’s approach as well as his departure from the master’s style. A comparison with a contemporaneous work on the same subject by Perugino is telling. The compositions are similar, with ready parallels evident between the placement of figures and the use of architecture. Yet Raphael’s space is more pronounced, his architecture more monumental, and his figures are imbued with a greater vitality. The younger man created a work that simultaneously met and surpassed the expectations of a market shaped by the older master. This ability to synthesize from and innovate upon the visual sources that he encountered—from his contemporaries or from the ancient world—was a definitive aspect of Raphael’s career.

Raphael, Madonna of the Meadow, 1505–06, oil on panel, 885 x 1130 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

In 1504, at the age of twenty-one, Raphael arrived in Florence. There, the young artist found a flourishing art market. He was able to gaze upon the powerfully expressive works of the early Florentine renaissance, and also encountered first-hand the work of local artists, including that of Leonardo da Vinci, whose influence is evident in several of Raphael’s Florentine paintings. The two portraits below recall Leonardo’s Mona Lisa.

In Florence, Raphael’s commissions were primarily for smaller, private paintings, such as the Madonna of the Meadow (1505) or his dual portraits of Agnolo and Maddalena Doni (1506). Local commissions for large-scale altarpieces—more desirable projects both for the higher prices they commanded and the public exposure they brought—eluded Raphael during these years. He did, however, continue to fulfil more prestigious projects for patrons outside of Florence, including in Siena, Urbino, and Perugia.

Raphael, Entombment, created for Atalanta Baglioni’s chapel, S. Francesco al Prato, Perugia, 1507, oil on panel, 184 x 176 cm (Galleria Borghese)

Raphael’s 1507 altarpiece for the Perugian widow, Atalanta Baglioni, is among the most groundbreaking works of his early career. The central panel depicting the Entombment of Christ is characterized by a forceful dynamism: figures’ bodies move and strain with tension created by strongly opposing diagonal lines. Raphael rejected the mood of quiet contemplation that usually characterizes altarpiece imagery in favor of energetic fervor. This daring departure from the altarpiece tradition anticipates the artist’s innovative work soon to come in Rome.

Raphael in Rome

Having never completed a large-scale project in Florence, Raphael left for Rome in 1508. He was drawn to the Eternal City by the powerful Warrior Pope, Julius II, who was in the process of re-vitalizing Rome. Julius was an astute patron. He recognized the potential of art and architecture to give material form to his vision for Rome as a new center of the Christian empire—one that would rival antiquity.

Raphael, School of Athens (left) and Disputà (right), fresco, 1509–1511 (Stanza della Segnatura, Papal Palace, Vatican)

Raphael was initially one of a number of artists hired by Julius to decorate his personal suite of rooms in the Vatican palace, a semi-public space where the pope’s interests were to be materialized in art. The first room he painted, the Stanza della Segnatura (Stanza means “room” in Italian), so perfectly aligned with Julius’s vision that the entire suite was given over to him. The two frescos known as the School of Athens and Disputà (1509–1510) on the opposing largest walls of the Stanza represent Philosophy and Theology respectively. Raphael infused non-narrative scenes with dramatic force. His figures engage in active dialogue and interact emotionally—no artist before him had presented immaterial concepts with such ingenuity.

Raphael, Galatea, c. 1513, fresco, Villa Farnesina, Rome, 9 feet 8 inches x 7 feet 5 inches

Raphael’s success in the papal suites lead to a flourishing Roman career informed by all he saw there. He studied with equal attentiveness the art and architecture of antiquity and the Roman work of his contemporaries, including Michelangelo, who was working on the Sistine Chapel ceiling while Raphael was undertaking the frescoes in the papal suites. Raphael worked for merchants and bankers, for popes and mighty statesmen.

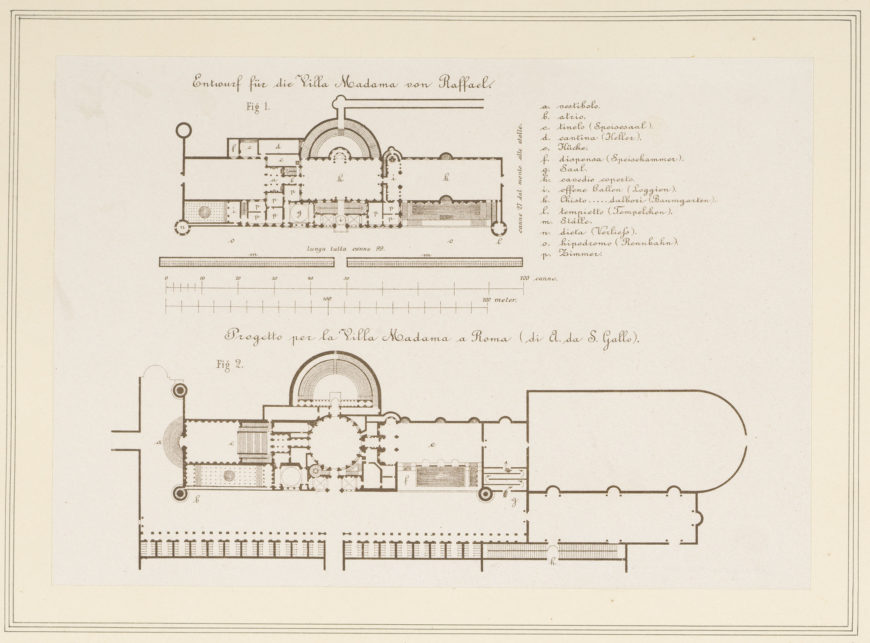

Plans of Villa Madama, after the original plan drawing in the Uffizi Galleries, Florence. Rudolph Redtenbacher, lithograph, published 1876, 18.7 x 26.9 cm (Prince Albert Royal Collections)

His enormous output included the spectacular mythological fresco cycle for the Roman pleasure villa of Agostino Chigi (the Villa Farnesina) and an elaborate series of tapestry designs on the life of St. Peter for the Sistine Chapel. He designed numerous buildings, such as the sumptuous Villa Madama (1518) just north of the Vatican, and was named lead architect of the new St. Peter’s in 1516. Partnering with the Bolognese engraver, Marcantonio Raimondi, Raphael provided drawings to be circulated as prints enabling his visual inventions to reach the widest possible audience. Religious or secular, private or public, Raphael’s work seamlessly reflected his synthesis of visual naturalism and classical idealism.

Raphael, tapestry cartoon for The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 320 x 390 cm (Victoria and Albert Museum)

Working method

Raphael worked well with others. He ran a large and complex workshop comprised of skilled collaborators who enabled him to realize numerous projects simultaneously. A shrewd manager and skilled teacher, Raphael provided highly detailed preliminary drawings for projects that could then be realized by his extensive and trusted workshop all under his meticulous eye. Raphael knew how to delegate to his team, capitalizing upon the strengths of those who worked for him.

Raphael, Transfiguration, 1518–1520, tempera on wood, 405 x 278 cm (Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City)

Gone too soon

On April 6, 1520—Good Friday that year—Raphael died. While Vasari attributes his early demise to an excess of amorous pursuits, the artist likely succumbed to sudden illness. The shock of his death reverberated throughout Rome. His corpse lay in state in his studio under his final finished work, the Transfiguration, before being interred in no less an exalted site than the Pantheon. His workshop and many projects underway passed into the capable hands of his assistants, Gianfrancesco Penni and Giulio Romano, who continued his legacy and fostered further the cult of Raphaelism. His death was universally understood as marking the end of an era. As lamented by his friend, Castiglione:

you rouse the envy of the gods above and death is outraged

that you can return the breath of life to things long dead, and

that what the long day had gradually effaced, this you were

preparing anew, spurning mortal law. Thus you fall, alas! [1]