Michelangelo, David, marble, 1501–04 (Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.)

A brief history of replicas

Copy of Trajan’s column, painted plaster cast, 523.5 cm high (The Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Reproductions of artworks are often derided as fakes or mere imitations, yet there is a rich tradition of replicas that dates to classical antiquity. Wealthy Romans commissioned copies of original Greek sculptures, many of which are featured in renowned collections today, including the Louvre and the Vatican Museums. Renaissance patrons also commissioned copies. The powerful Medici Family, for example, commissioned a replica of the marble Laocoön, an ancient Roman statue that was itself a copy of an earlier lost version in bronze, which remains on display in the Uffizi Museum in Florence. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, museums had galleries of plaster casts, which functioned primarily as study tools for artists and art historians. London’s Victoria and Albert Museum still has an impressive cast collection, which includes dozens of sculptures and even a complete cast of the 125-foot-tall Column of Trajan.

Bronze Replica of Michelangelo’s David by Clemente Papi, 1866, added to Piazzale Michelangelo in 1875 (photo: James Fishburne)

Replicating a Renaissance master

Carrara marble replicas by Andreini Studio, Medici Madonna, 1930, Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California (photo: James Fishburne)

Replicas form a vital component of Michelangelo’s legacy, as they have helped transform him into a global cultural icon. The well-known Italian renaissance artist achieved unprecedented levels of fame during his own lifetime, and since the nineteenth century his work has been copied and displayed in prominent locations throughout the world. In 1856 the Grand Duke of Tuscany sent a plaster cast of Michelangelo’s colossal David to London as a gift for Queen Victoria. In 1875 the city of Florence placed a bronze replica of David in Piazzale Michelangelo, a public space created to honor the artist, while in 1910 a marble copy was installed in front of the Palazzo Vecchio (Florence’s town hall) to replace the original David, which had been moved from this location into the Galleria dell’Accademia several decades earlier.

Other full-size copies of David are publicly displayed far from Italy, including in world capitals such as Mexico City and Copenhagen. One of the largest collections of Michelangelo replicas, which was created in the 1920s and 1930s, is located at Forest Lawn Memorial Park, in Glendale, California. The statues in Forest Lawn’s collection were sculpted in Florence, and they include the Pietà, David, Madonna of Bruges, Moses, Night, Day, Twilight, Dawn, and the Medici Madonna—sculptures that span four decades of the artist’s career.

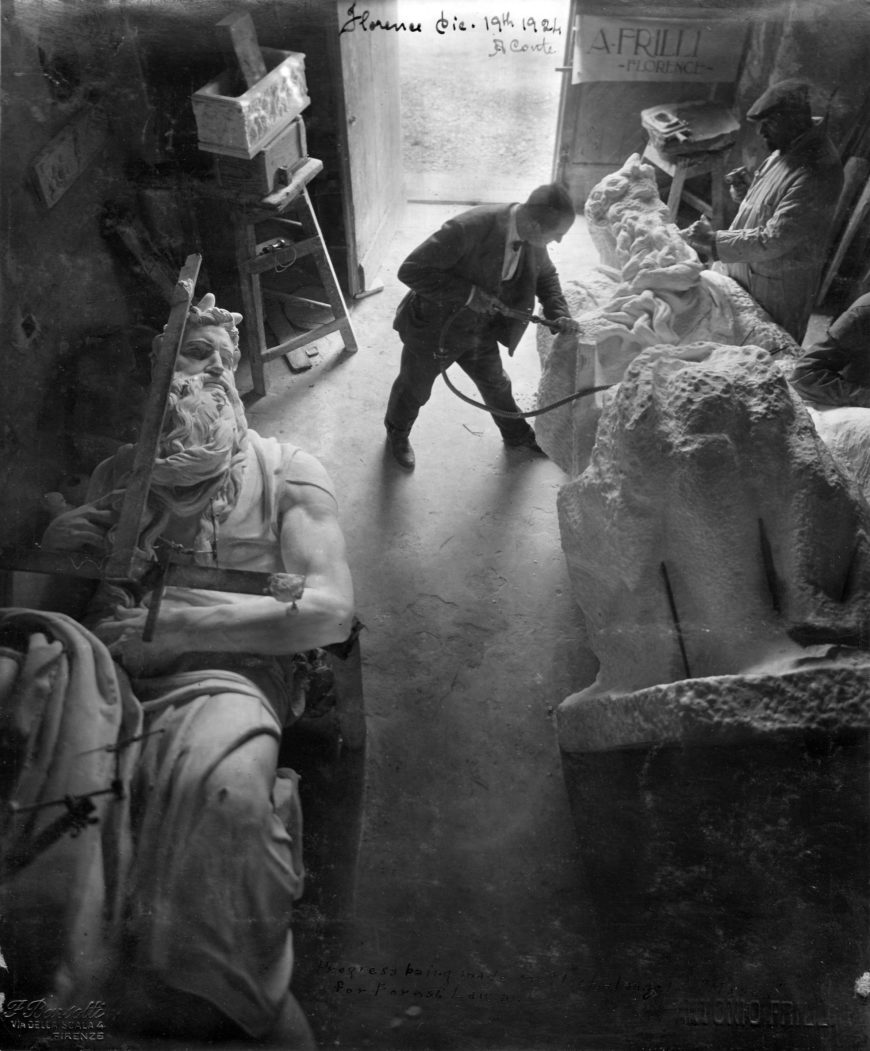

Oreste Andreini sculpting a replica of Michelangelo’s Moses, 1924 (photo: Forest Lawn Museum Archive).

How were the copies made?

Replicating a sculpture with exacting precision requires great artistic ability and significant technical skill. Bronze copies are typically created using a mold of the original statue and the “lost wax” technique, while marble replicas must be hand sculpted. Even with technological advances such as 3D printing and computer-guided routers, the vast majority of fine-art sculpting in marble is still done by hand. The artist relies on a device invented in the eighteenth century called a “pointing machine” (from the Italian macchinetta di punta). Similar devices, albeit in a more rudimentary form, were used by sculptors in ancient Rome. In a 1924 photo we see the Florentine artist Oreste Andreini working on Forest Lawn’s copy of Moses. Andreini used a plaster cast of the original sculpture (seen here on the left), and a new block of marble. He took hundreds of measurements or “points” from the cast and painstakingly chiseled them into the stone. At this stage in the process, the form of Moses is clearly visible, but he appears almost pixelated. It would still take months of work before the artist completed the sculpture and his team of assistants polished it. Andreini is part of the rich tradition of marble sculpting that has persisted in Florence for centuries. He was a member of the city’s Accademia delle Arti del Disegno (Academy of the Arts of Design)—Michelangelo had been a member of the same academy in the sixteenth century.

Carrara marble replicas by Andreini Studio, (right to left) Michelangelo’s Pietà, Madonna of Bruges, and Medici Madonna, 1930, Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California (photo: James Fishburne)

What is lost and what is gained?

Marble quarry in the Apuan Alps, over the town of Carrara, Italy (photo: Michele Buzzi, CC BY 2.5)

No matter the skill level of an artist, it is impossible to perfectly capture every detail of a statue in a replica. While scale is easy for a trained sculptor to recreate, the surface texture of a copy often differs from the original and the color of stone can vary subtly. This is because each block of marble is unique. Michelangelo typically used stone from Carrara, Italy, and since this quarry is still in operation, many twentieth- and twenty-first-century replicas also use Carrara marble. Despite this shared origin, the grain within each block of marble differs slightly and tiny blemishes in the material are never identical, even if these differences are only perceptible to a trained observer.

There are many benefits, both aesthetic and educational, which only replicas can provide. The most obvious is access and availability for broad audiences. Many replicas of Michelangelo’s work are between 90 and 150 years old, and transatlantic flights were not widely available until after World War II, making international travel prohibitively slow, and even today it remains expensive. Replicas also allow for side-by-side comparisons that are impossible even if one can travel to Italy. Michelangelo’s masterpieces are spread throughout numerous churches and museums in multiple cities, but with full-size copies, one can see a variety of his sculptures at the same time. Artworks from different phases in Michelangelo’s career can be viewed together, allowing the general public and scholars to make comparisons and observe how his style developed over the course of his life. At Forest Lawn, for example, one can view the Pietà (1498–1499), the Bruges Madonna (1501–1504), and the Medici Madonna (1521–1534) in the same space, which is an opportunity that Michelangelo himself was never afforded.

Replicas and the creation of artistic legacy

Replicas of Michelangelo’s David at “Youngwood Court” in Los Angeles, decorated for Christmas 2005 (photo: Stomme, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Michelangelo’s work has been replicated many times because the original sculptures are revered as exemplars of artistic achievement. The replicas function as surrogates for his originals, allowing for an expanded viewership both within the Florentine urban landscape and around the globe. Whether you are walking through Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, visiting a small town in Japan, or watching a Lady Gaga video, it is possible to encounter Michelangelo’s work in an array of contexts. Interestingly, the relationship between originals and copies is reciprocal. The increased visual presence created by replicas contributes to the artist’s already considerable stature, and with greater stature, there is more demand for visiting the original artworks. Ultimately, both the replicas and original sculptures speak for Michelangelo, and these physical manifestations are more persuasive than the praise of any critic or fellow artist. Together, the originals and the copies have reinforced Michelangelo’s prominent place in the canon of Western art, and both continue to offer rewarding viewing experiences.