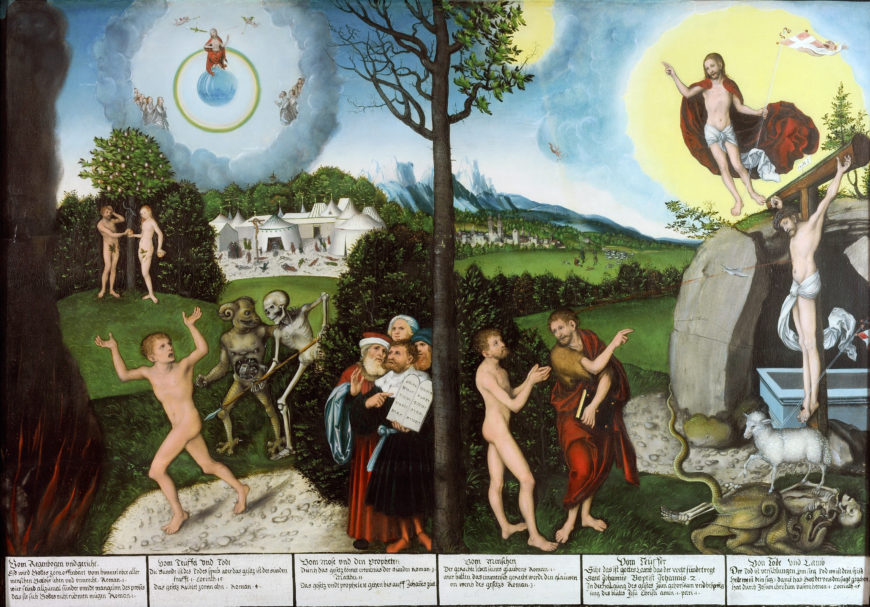

Lucas Cranach, The Law and the Gospel, c. 1529, oil on wood, 82.2 × 118 cm / 32.4 × 46.5 in (Herzogliches Museum, Gotha, Germany)

How to get to heaven?

How exactly do you get to heaven? Good deeds? Can you get yourself to heaven on your own merit or do you have to sit back and let God do the work? These questions caused international controversy, mass looting, vandalism, and killing in the sixteenth century. One casualty of the violence and chaos was the destruction of thousands of works of religious art. Iconoclasts (breakers of likenesses/images) stormed through churches, destroying every work of art they could get their hands on. How did heaven get to be so controversial?

The most influential image of the Lutheran Reformation

These questions are answered in a surprising kind of picture called The Law and the Gospel, originally painted by the artist Lucas Cranach the Elder in 1529. The Law and the Gospel is the single most influential image of the Lutheran Reformation. The Reformation, initiated by Martin Luther in 1517, was originally an attempt to reform the Catholic Church. However, reform quickly became rebellion, as people began to question the power and practices of the Catholic Church, which had been the only church in western Europe up until Luther.

The role of art

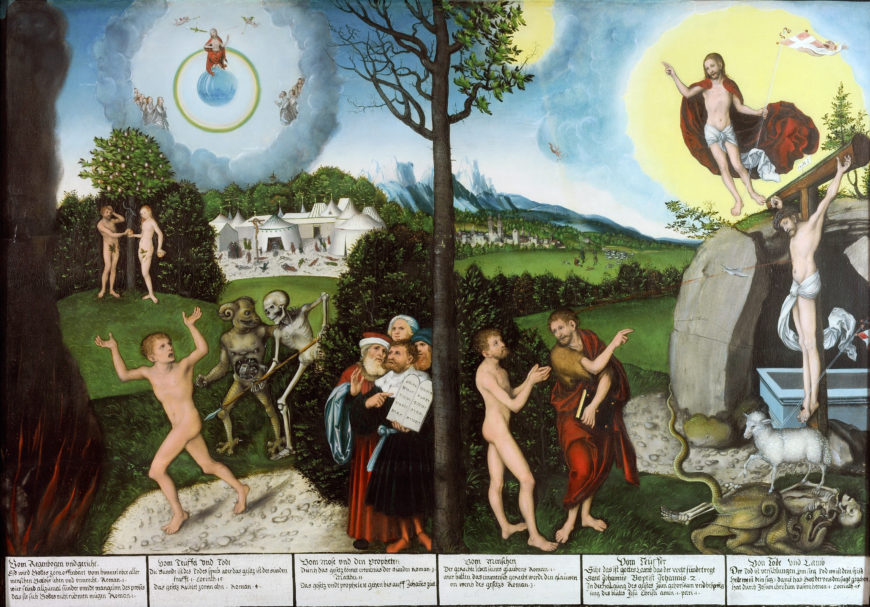

John the Baptist pointing a man toward Christ (detail), Lucas Cranach, The Law and the Gospel, c. 1529, oil on wood, 82.2 × 118 cm / 32.4 × 46.5 in (Herzogliches Museum, Gotha, Germany)

A decisive difference between Catholics and followers of Luther was the question of how to get to heaven, and what role, if any, religious art could play. The Catholic Church insisted that believers could take action to vouchsafe their salvation by doing good deeds, including making financial donations and paying for elaborate art to decorate Christian churches. Luther, however, insisted that salvation was in God’s hands, and all the believer had to do was to open up and have faith. As people became disillusioned with Catholic teaching, they grew angry about the ways the Catholic Church became rich in money, art, and power. When reform became impossible and rebellion the only course of action, furious, frustrated believers directed their anger at works of art, an easy and powerful target.

Other reformers followed Luther’s example and staged rebellions against the Catholic Church. Some reformers took a strong position against religious art, forbidding it entirely. Luther however was more moderate, and believed that some religious art was acceptable provided it taught the right lessons, and this is where The Law and the Gospel comes in.

Luther’s ideas in visual form

In consultation with Martin Luther, Lucas Cranach the Elder produced The Law and the Gospel. All of Cranach’s Lutheran painting rests upon this pictorial type, which also influenced other artists. The Law and the Gospel explains Luther’s ideas in visual form, most basically the notion that heaven is reached through faith and God’s grace. Luther despised and rejected the Catholic idea that good deeds, what he called “good works,” could play any role in salvation.

Lucas Cranach, The Law and the Gospel, c. 1529, oil on wood, 82.2 × 118 cm / 32.4 × 46.5 in (Herzogliches Museum, Gotha, Germany)

In The Law and the Gospel, two nude male figures appear on either side of a tree that is green and living on the “Gospel” side to the viewer’s right, but barren and dying on the “law” side to the viewer’s left. Six columns of Bible citations appear at the bottom of the panel.

Right (“gospel”) side

On the “gospel” side of the image (the right side), John the Baptist directs a naked man to both Christ on the cross in front of the tomb and to the risen Christ who appears on top of the tomb. The risen Christ stands triumphant above the empty tomb, acting out the miracle of the Resurrection. This nude figure is not vainly hoping to follow the law or to present a tally of his good deeds on the judgment day. He stands passively, stripped down to his soul, submitting to God’s mercy.

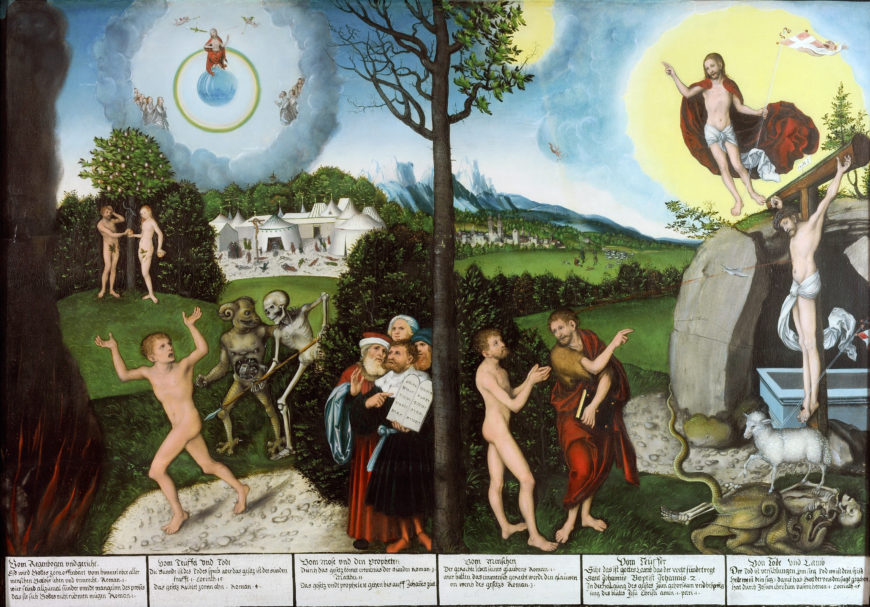

Demon and skeleton force a man toward hell, while prophets stand on right (detail), Lucas Cranach, The Law and the Gospel, c. 1529, oil on wood, 82.2 × 118 cm / 32.4 × 46.5 in (Herzogliches Museum, Gotha, Germany)

Left (“law”) side

In the left foreground a skeleton and a demon force a frightened naked man into hell, as a group of prophets, including Moses, point to the tablets of the law. The motifs on the left side of the composition are meant to exemplify the idea that law alone, without gospel, can never get you to heaven.

Adam and Even eating the fruit of the knowledge of good and evil, with Christ above in judgment (detail), Lucas Cranach, The Law and the Gospel, c. 1529, oil on wood, 82.2 × 118 cm / 32.4 × 46.5 in (Herzogliches Museum, Gotha, Germany)

Christ sits in Judgment as Adam and Eve (in the background) eat the fruit and fall from grace. Moses beholds these events from his vantage point toward the center of the picture, his white tablets standing out against the saturated orange robe and the deep green tree behind him, literally highlighting the association of law, death, and damnation.

Taken together, these motifs demonstrate that law leads inescapably to hell when mistaken for a path to salvation, as the damned naked man demonstrates.

God judges and God shows mercy

The Law and the Gospel is concerned with two roles that God plays, to judge and to show mercy. On the one hand, God judges and condemns human sin; but on the other hand, God also shows mercy and forgiveness, granting unearned salvation to sinful believers. As Reformation scholar Bernhard Lohse explains:

The Word of God encounters people as law and as gospel, as a word of judgment and as a word of grace…. It is certainly true that there is more law than gospel in the Old Testament and more gospel than law in the New Testament. Luther’s distinction between law and gospel, however, referred to something other than the division of biblical statements into the two parts of the biblical canon. This distinction rather describes the fact that God both judges and is merciful. [1]

Luther’s idea of law is multifaceted, and bears a complex relationship to his idea of gospel. Though law alone will never make salvation possible, it remains indispensable as the way the believer recognizes sin and the need for grace. Law paves the way to salvation by preparing the way for grace.

Lucas Cranach, The Law and the Gospel, c. 1529, oil on wood, 82.2 × 118 cm / 32.4 × 46.5 in (Herzogliches Museum, Gotha, Germany)

Although The Law and the Gospel includes events from both the New and the Old Testaments, it is not a simple contrast of Christianity and Judaism. If The Law and the Gospel simply distinguished between the Old and New Testaments—or even more broadly between Judaism and Christianity—then it would not be specifically Lutheran or new, art historically or theologically. Instead, The Law and Gospel concerns two aspects of the relationship between humanity and God, a relationship based on human action on the one hand, and divine power on the other. The Law and Gospel describes events throughout the Bible which reveal the dual aspect of God’s relationship to people.

The Law and the Gospel is Lutheran because it represents Cranach’s pictorial translation of Luther’s unique understanding of salvation. The painting interprets the roles of law, good works, faith, and grace in the human relationship to God.

Note: The Law and the Gospel is frequently called Law and Grace, a title which derives from a version of the painting in Prague, where the terms “Gesecz” (Law) and “Gnad” (Grace) are boldly painted and plainly visible.