Van der Weyden captures grieving bodies with meticulousness and compositional rhythm.

Rogier van der Weyden, The Descent from the Cross, before 1443, oil on panel, 204.5 x 261.5 cm (Prado Museum, Madrid). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

[music]

0:00:06.6 Dr. Steven Zucker: We’re in the Prado in Madrid looking at one of their most spectacular paintings.

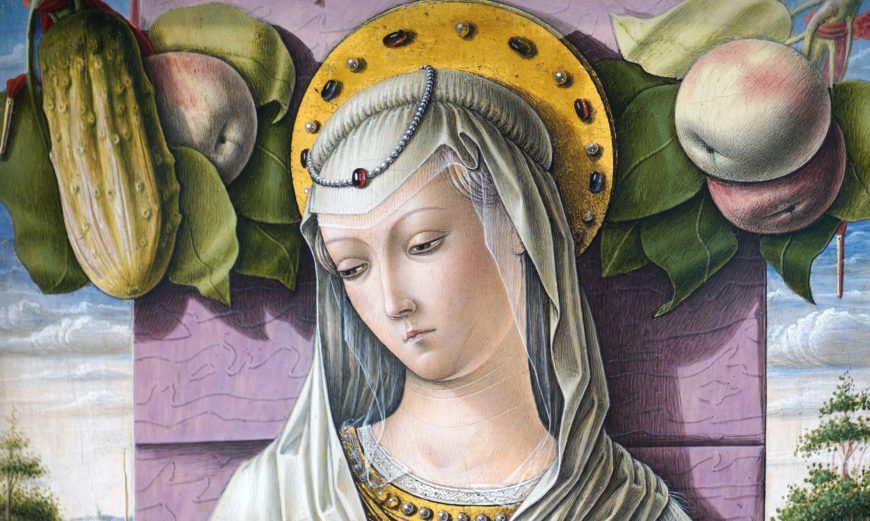

0:00:12.5 Dr. Beth Harris: By Rogier van der Weyden, one of the great artists of the Northern Renaissance. What we’re seeing is a standard subject in the life of Christ, where Christ’s body is removed from the cross. It has a lifelikeness, a vividness that makes you feel as though these figures are present in the room with you. They’re basically life-size.

0:00:34.6 Dr. Steven Zucker: The figures are so beautifully composed that they seem like they can’t move even a finger without destroying the harmony of the scene.

0:00:44.3 Dr. Beth Harris: There’s a kind of realism and precision that we expect of the Northern Renaissance, but at the same exact time, they’re in a space which is impossible for them to occupy.

0:00:56.6 Dr. Steven Zucker: The figures are placed against this very shallow background. We’re actually in a kind of box. It’s a curious choice. We don’t have a deep landscape; we don’t have atmospheric perspective. What we have are these figures that almost seem to be sculpture.

0:01:13.9 Dr. Beth Harris: It’s important to remember that there were many wooden sculpted altarpieces created during the 15th and 16th centuries, and they were painted.

0:01:24.8 Dr. Steven Zucker: The environment of the box is not only akin to sculpture, but in this context, the figures seem more concentrated, more powerful, larger. They almost don’t fit in the box. If Saint John the Evangelist, who we see in red on the left, were to stand up, he might hit his head. But there are other ways that the artist has achieved this sense of focus. He’s removed the landscape. He’s removed unnecessary figures. In some paintings of this period, you might see towns in the distance. All of that has been taken away. And what we’re left with is the most essential aspects. In fact, what we’re left with is the ensemble that is specifically mentioned within the Bible.

0:02:06.2 Dr. Beth Harris: We have the three Marys, one of whom is the Virgin Mary, Christ’s mother. But the Gospels also refer to other women who were named Mary, who were present. We have Saint John. We also see Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea. There are two additional figures. One is the figure who’s climbed the ladder to lower Christ’s body. And we see another figure in between, Mary Magdalene and the beautifully dressed figure of Joseph of Arimathea.

0:02:35.4 Dr. Steven Zucker: Each figure is expressive of a degree of sorrow, of grief, that is incredibly moving.

0:02:42.6 Dr. Beth Harris: The word that was used by theologians is compassio, Latin for compassion. That idea that these figures are partaking in Christ’s pain, and they express it differently. The figure on the upper left holds a cloth to her eyes, and we see tears streaming down her face. Mary Magdalene, on the far right, expresses her feelings powerfully, but with a very graceful movement to her body, where she clasps her hands in front of her as her body forms an arc that leans in toward Christ.

0:03:20.0 Dr. Steven Zucker: And that arc is echoed by the arc of Saint John on the opposite side, who reaches down to assist the Virgin Mary, who has fainted in her grief. The Virgin Mary, here among these mourners, is singled out for the intensity of her pain, a pain that exists both internally, emotionally, but also physically. The composition of her body echoes the composition of Christ, these two arcs that fit together, and so visually, they are linked.

0:03:49.2 Dr. Beth Harris: And if you look closely, you see Christ’s right arm dangles down lifelessly. The same is true of Mary’s right arm. Her left arm is held up just the way that Christ’s left arm is held up. We know that Christ’s death on the cross redeems mankind. But here we’re also told of the importance and necessity of both Christ and Mary to the redemption of mankind.

0:04:15.7 Dr. Steven Zucker: It’s so interesting to look at this painting because it’s so large, whereas so many of Rogier van der Weyden’s surviving paintings are on a much smaller scale. And it’s a reminder that this was an altarpiece and that this would have been placed in a chapel, in a church, and that mass would have been performed in front of it.

0:04:34.1 Dr. Beth Harris: This was actually commissioned by the confraternity of crossbowmen that had their own chapel in the Church of Our Lady in Leuven. And so, although we see it today in a museum context, it’s so important for us to remember that in front of this would have been an altar, that the priest stood at the altar and raised the wafer that, when consecrated, miraculously becomes the body of Christ.

0:05:01.9 Dr. Steven Zucker: And the priest elevates the host, that is the wafer, so that it’s visible to the congregation, just the way that Christ here is made visible to us. Although there is no landscape, there is grass. There are stones as well as a human skull. And this is a reference to the location where Christ was crucified: Golgotha.

0:05:22.4 Dr. Beth Harris: It refers to the legendary idea that Christ was crucified at the site of Adam’s burial. So that we have this idea of Adam causing the fall into sin and the possibility of salvation offered by Christ’s death.

0:05:39.5 Dr. Steven Zucker: I can’t look at this painting without spending time thinking about the choices that the artist made in terms of color and texture, because they are so beautifully handled. Look at the rich reds that John wears, the brilliant blue that catches our eye and draws our attention to the Virgin Mary, but then the subtle use of color in Mary Magdalene’s outfit. We see a little bit of light green, a kind of light purple, some grays, and of course, those lovely red sleeves. And in terms of textures, just look at the gems that hem Nicodemus’s outfit. They’re brilliant. Or the rich brocades worn by Joseph of Arimathea. And even if we look at the clothing of the woman in green, look at the fur that lines her dress and the way that as the fabric breaks, the fur comes apart. It feels so absolutely real, so soft.

0:06:32.6 Dr. Beth Harris: And yet the fabric also seems to have a life of its own. It breaks in unexpected ways. It twists and turns. This is most obvious in the figure who’s climbed up the ladder, who holds nails in his hands that he’s removed from Christ’s body. And we see his prayer cloth, this sash that seems to flutter in the wind. But of course, we’re in this windowless, airless box, and so that doesn’t even make sense. But this kind of attention to tiny details, like the blood on the nails, is so typical of the Northern Renaissance. But so is this over-complication of drapery, of fabric, all the while paying attention to its textures. When we look at Christ’s body, we see the ribs, his abdomen, flattened back. We have a sense of the muscles in his abdomen and hips, the muscles in his arms. As the left arm is lifted, we see the veins in his forearm. His body is so real, it’s as though we could reach out and touch it. The blood from where he was pierced, the blood from the crown of thorns. This is a painting that asks of us an incredible degree of emotional involvement.

[music]