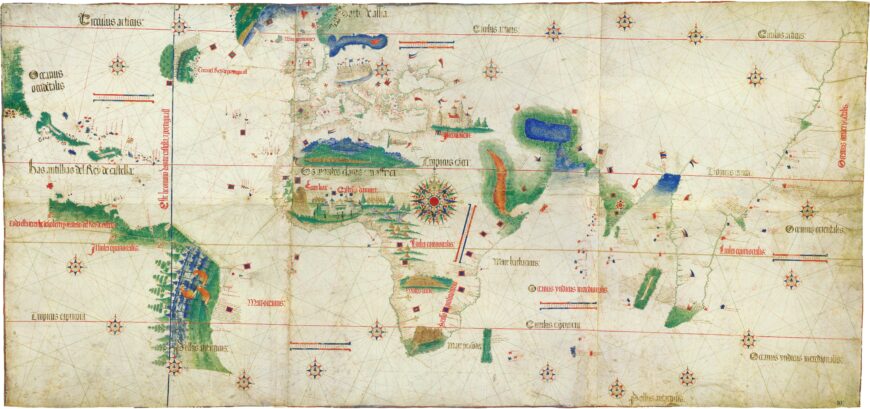

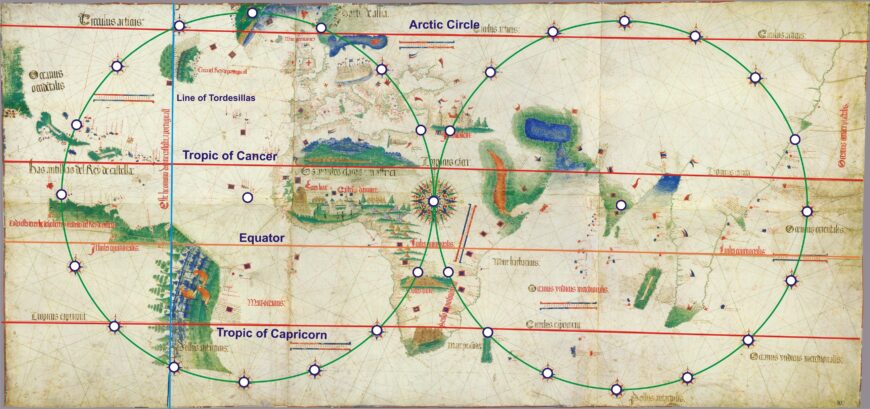

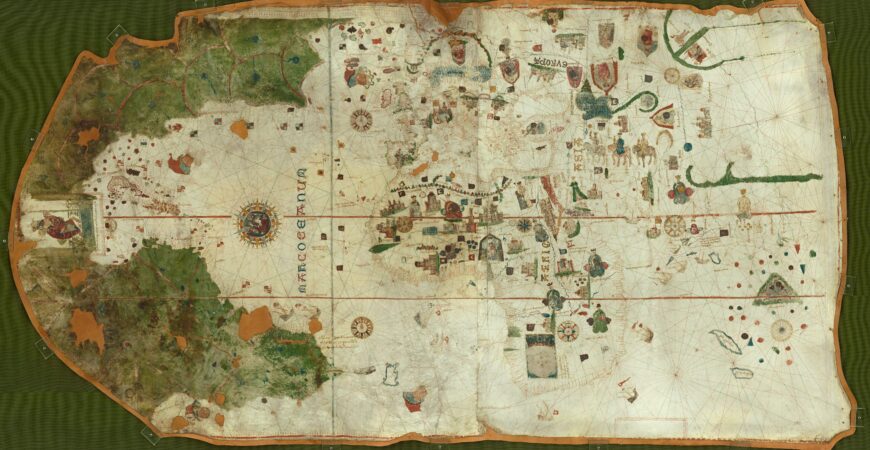

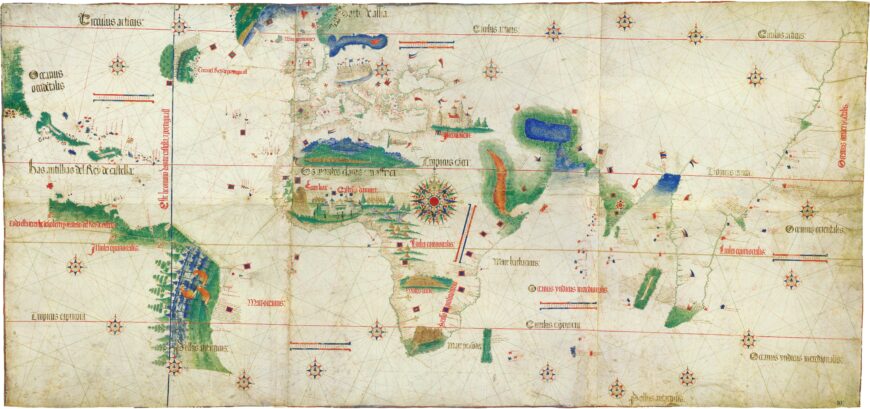

Cantino Planisphere, 1502, ink and pigment on vellum, 102 x 218 cm (Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena)

The Cantino planisphere, made by an unknown Portuguese chartmaker, depicts what the Portuguese knew of the world in 1502. Unlike a map that emphasizes landmasses, a chart, like this one, focuses on bodies of water and coastlines.

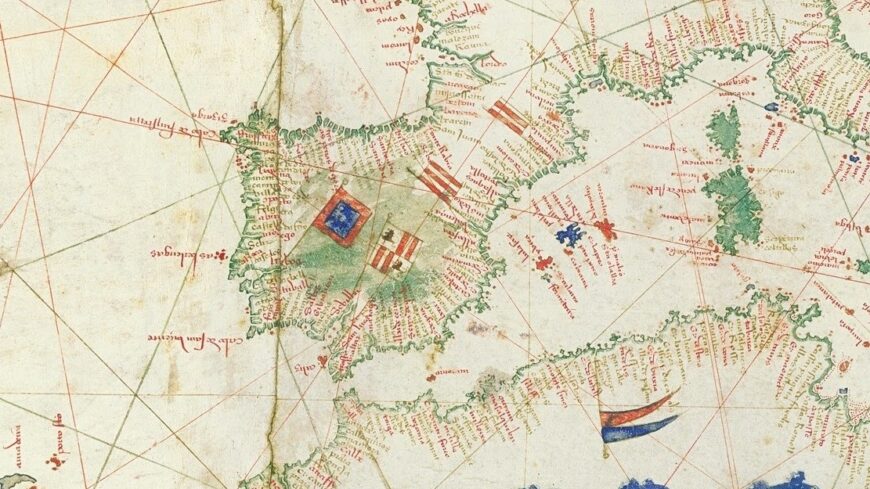

Europe and North Africa (detail), Cantino Planisphere, 1502, ink and pigment on vellum, 102 x 218 cm (Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena)

The coasts of Europe and Africa are carefully delineated whereas the Americas and Asia are fragmentary; Australia and the Pacific islands are missing. Although the absences are striking today, this large chart offered European viewers groundbreaking new information. The Portuguese were pioneers in sailing from Europe throughout the Atlantic and into the Indian Ocean. Geographic information about overseas routes and trade opportunities was so valuable that the Italian agent Alberto Cantino, after whom the chart is named, smuggled the planisphere from Portugal to Italy in October 1502 (the Duke of Ferrara had paid Cantino to gather information about Spanish and Portuguese navigation and the merchandise arriving from overseas).

In the fifteenth century, the Portuguese embarked on an extensive mission to explore new maritime routes. One of the king’s sons, Prince Henry the Navigator, sought to gain wealth by promoting voyages to powerful African kingdoms known to have gold and enslaved people. During Prince Henry’s lifetime Portuguese ships began to travel south of the Canary Islands along the western coast of Africa. These expeditions and the many that followed gathered the information contained in the Cantino planisphere. In 1498 Vasco da Gama’s expedition sailed around the Cape of Good Hope at Africa’s southernmost tip and reached India.

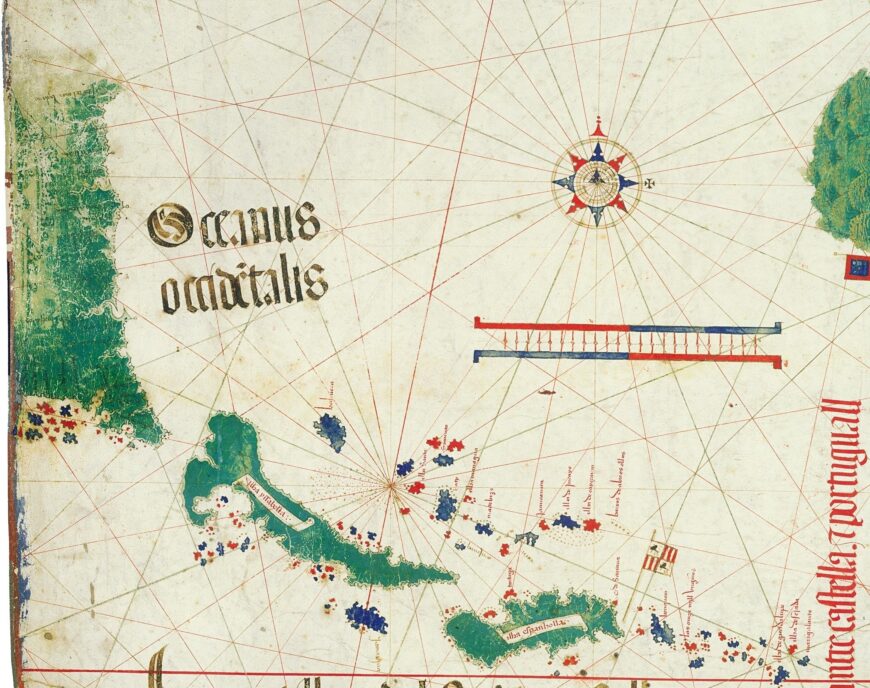

Upper left corner of the map showing the Caribbean, the east coast of North America, including Newfoundland (detail), Cantino Planisphere, 1502, ink and pigment on vellum, 102 x 218 cm (Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena)

The planisphere’s depiction of the Caribbean derives from numerous Spanish voyages, including Christopher Columbus’ first three trips across the Atlantic that began in 1492. In 1487 British ships reached Newfoundland (shown as an island in the Cantino chart’s upper left corner), and Portuguese vessels visited the area in 1501.

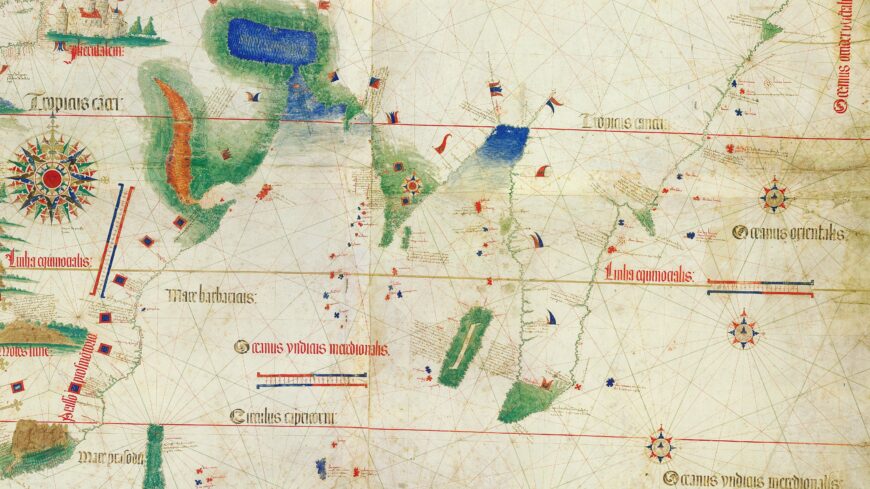

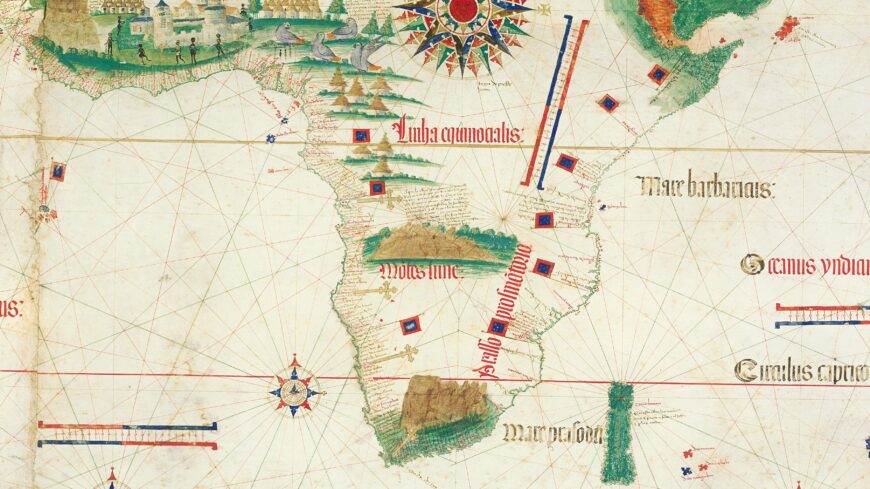

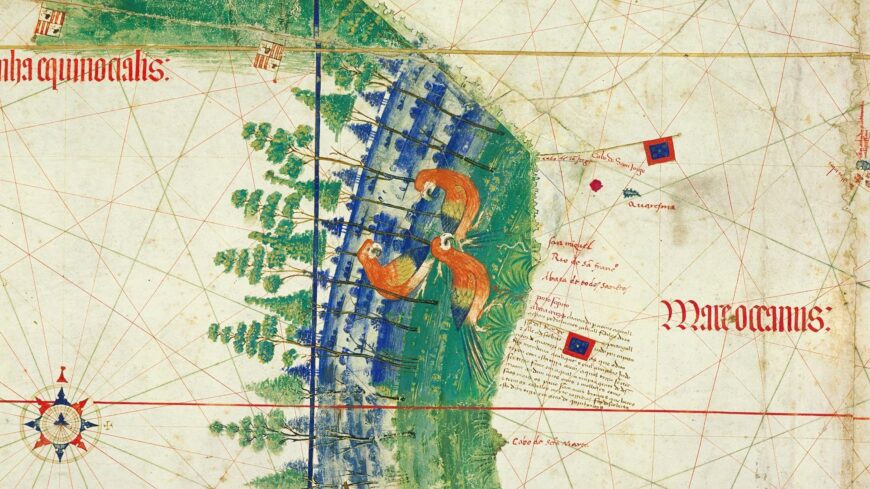

The coast of Brazil in South America and the Coast of Africa (detail), Cantino Planisphere, 1502, ink and pigment on vellum, 102 x 218 cm (Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena)

Pedro Álvares Cabral’s ships landed in Brazil in 1500, and Gonçalo Coelho’s expedition explored more of the Brazilian coast the following year, allowing the Cantino chart to present the first known depiction of Brazil’s eastern coast. Captain João da Nova returned to Lisbon in September 1502 after having sailed past the islands Ascension and St. Helena, shown in the Cantino planisphere correctly positioned in the Atlantic just south of the equator.

The coast of Africa, India, and Southeast Asia (detail), Cantino Planisphere, 1502, ink and pigment on vellum, 102 x 218 cm (Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena)

Although Vasco da Gama, Pedro Álvares Cabral, and João da Nova’s voyages explored the coast of India and confirmed the subcontinent’s triangular shape as depicted in the planisphere, the rest of Asia remained largely a matter of speculation. Sailing from West Africa to India required the expertise of local navigators or merchants familiar with the route. These men supplied the Portuguese with additional information about ports and resources further east. The Cantino chart relies on this information as well as older maps for its depiction of Asia.

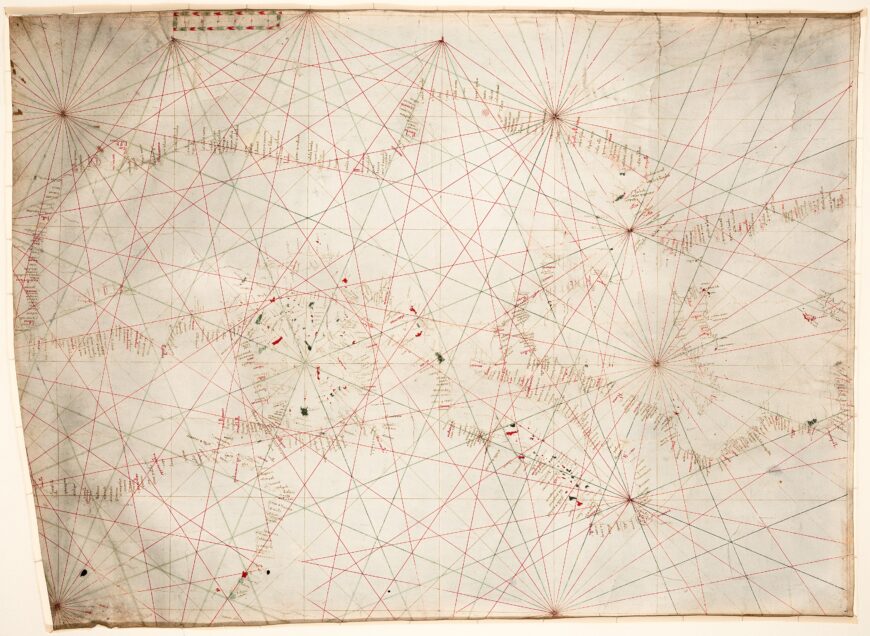

Portolan chart of the Mediterranean sea, with north at the bottom and south at the top, c. 1320–1350, ink on vellum (Library of Congress)

Visualizing the world

The Cantino planisphere focuses on coastlines and how they relate to compass directions as indicated by the lines that crisscross the surface, called rhumb lines. This visual language stems from portolan charts, such as this one of the Mediterranean sea. This chart would have been used on ships along with log books that record the position of the sun and stars, winds, currents, geographic features, and other information that was useful for navigation. In addition, navigators used compasses and mariner’s astrolabes—a tool that measures the position of the sun and stars, and enables calculation of the latitude.

The rhumb-line construction scheme in the Cantino planisphere (Alvesgaspar, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Unlike portolan charts, the Cantino planisphere also indicates latitude with horizontal lines representing the equator, Arctic Circle, and tropic of Cancer and Capricorn.

Markers are indicated by crosses, detail of southern Africa, Cantino Planisphere, 1502, ink and pigment on vellum, 102 x 218 cm (Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena)

When Portuguese explorers arrived at a new site, they often erected a stone marker called a padrão and measured the latitude. The Cantino chart indicates the location of these markers with crosses. Despite these rhumb lines and latitude markers, the Cantino planisphere would not have been used on ships. Instead, it was probably admired in a private study, and shown to chartmakers and navigators who could use it to make other charts and to plan exploratory voyages.

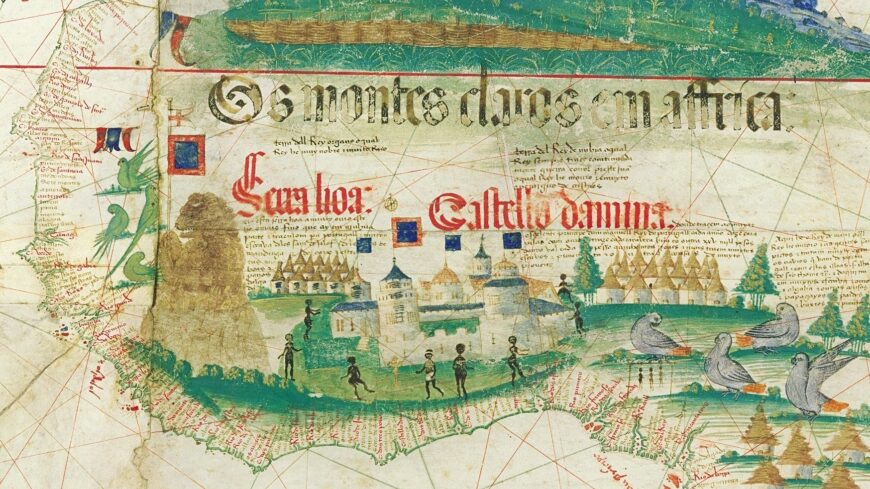

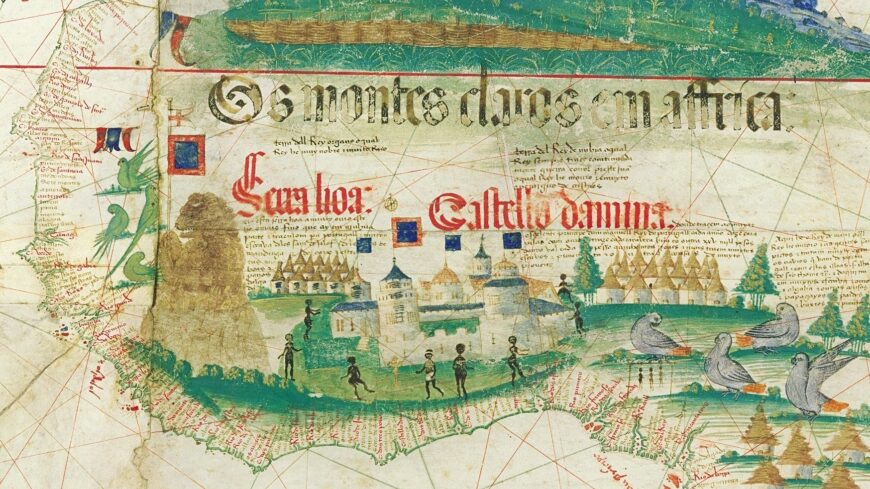

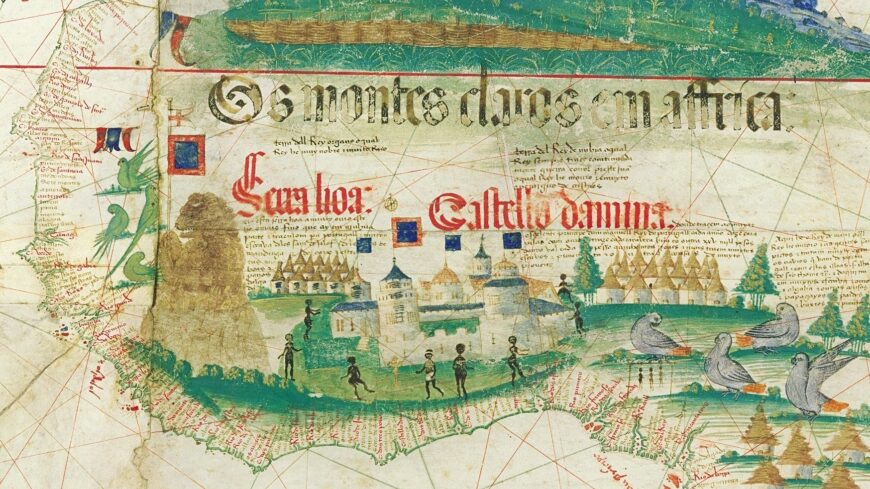

West Africa (detail), Cantino Planisphere, 1502, ink and pigment on vellum, 102 x 218 cm (Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena)

Rife for exploitation

The text and imagery emphasize resources that the new sea routes made available for trade. Columbus famously attempted to sail around the globe to access Asian spices, and the wealth that could be gained from overseas trade also incentivized other voyages. In the planisphere, texts along coasts list the local merchandise that was highly desirable among European consumers. In Asia, these include a variety of spices and textiles, precious gems, gold and silver, ivory, and porcelain. African sites are described as being rich in gold, and as sources of fine raffia mats, parrots, spices, and people who could be enslaved.

Standards of Portugal (red and blue) and Spain (red and white) (detail), Cantino Planisphere, 1502, ink and pigment on vellum, 102 x 218 cm (Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena)

The chart is biased in favor of the Portuguese who wished to dominate overseas trade. Standards placed along the coasts indicate which ruler has claimed control of those lands, and the Portuguese standard appears far more often than any other.

The chart also includes the vertical demarcation line of the Treaty of Tordesillas 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands (the strong black line that runs through Newfoundland and Brazil). In 1494, the Spanish and Portuguese agreed that everything west of this line belonged to Spain and everything east to Portugal, effectively giving Spain the Americas while Portugal received Africa and Asia. A few years later, the Portuguese used the treaty to claim Brazil. In addition, the Cantino chart incorrectly places Newfoundland east of the treaty line claiming it for Portugal. Large red letters label Newfoundland as “Land of the King of Portugal.” This underscores how questionable European claims to lands were. Not only does the chart disregard the local inhabitants, but it also overlooks that the British, who were not included in the Treaty of Tordesillas, had explored Newfoundland before the Portuguese.

Subjectivity and artistry

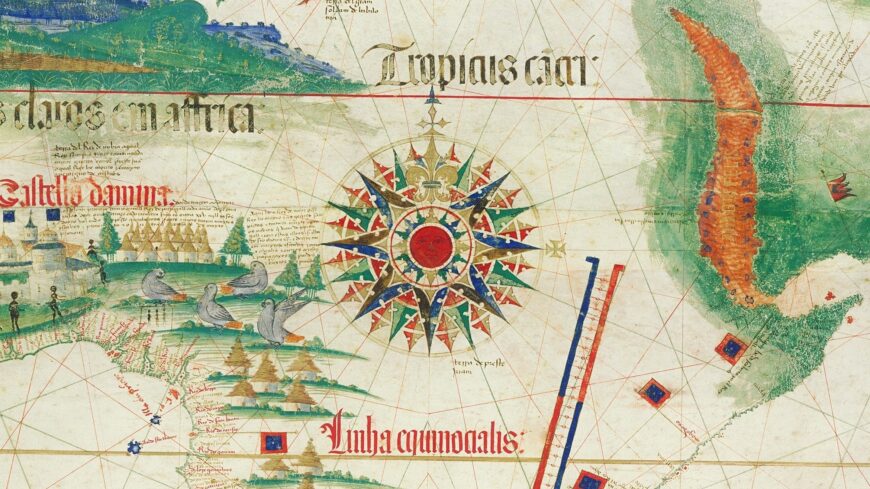

Compass rose, Cantino Planisphere, 1502, ink and pigment on vellum, 102 x 218 cm (Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena)

Maps and charts are often viewed as objective displays of information; however, they require choices to be made about what to include, what to exclude, and how to represent data. For instance, on typical maps used today, space is distorted in a way that privileges the northern hemisphere, making places such as Europe and North America seem larger in comparison to areas in the south. The Cantino planisphere challenges some of the previously existing conventions for depicting the globe and organizes the earth’s landmasses in new ways. A large and elaborate compass rose in Africa marks the center of the world. This rose intersects with two circles that are made of smaller compass roses—as indicated from the diagram above showing the rhumb-line construction. These circles divide the world into the western and eastern hemispheres, an approach to visualizing the globe that clearly separates the Americas from Asia, an idea not everyone had yet accepted.

Juan de la Cosa, World Map, rotated to place north at the top, c. 1500, pigment on parchment, 96 x 186 cm (Museo Naval de Madrid and Biblioteca Virtual del Ministerio de Defensa)

For instance, Juan de la Cosa’s chart, originally oriented with west at the top, asserts that the Caribbean is connected to Asia. La Cosa had traveled the Caribbean with Columbus and had also explored the northern coast of South America, which he depicts as a large green landmass stretching toward Africa.

Venice and Jerusalem (detail), Cantino Planisphere, 1502, ink and pigment on vellum, 102 x 218 cm (Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena)

Certain parts of the world are emphasized in the Cantino planisphere with paintings of buildings, people, and animals. Clusters of towers surrounded by crenellated walls and colonnades highlight three cities: Jerusalem, Venice, and São Jorge da Mina. While Jerusalem is central to the Christian religion, the other two cities relate to trade. Situated at the border of Christian Europe and the Ottoman Empire, Venice gained great wealth as a mediator in exchange between Asia and Europe. São Jorge da Mina was a trading post established in 1482 from which the Portuguese interacted with nearby African kingdoms.

West Africa (detail), Cantino Planisphere, 1502, ink and pigment on vellum, 102 x 218 cm (Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena)

Regions that Portuguese expeditions had only recently made accessible to Europeans—the west coast of Africa and east coast of Brazil—feature the most imagery. Sierra Leone is marked with a lion in reference to the Portuguese name for the region, and clusters of huts appear throughout west and central Africa. Although it is unclear whether one of these groups of buildings is intended to represent the impressive royal city of Benin, a block of text describes the Oba (king) of Benin and the rich trade that the Portuguese conducted with this kingdom.

The coast of Brazil (detail), Cantino Planisphere, 1502, ink and pigment on vellum, 102 x 218 cm (Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena)

Both Africa and Brazil contain parrots, birds that wealthy Europeans considered exotic collectibles. Both regions also feature trees, a sign of their natural abundance. In Brazil, the trees suggest what will soon become an important export: Brazilwood, a wood that produces red dye and eventually gave the land its name. Spanish travelers had already noted the wealth of tall sturdy trees in the Caribbean, a valuable resource that was necessary for the construction of ship masts. With its focus on resources that are accessible to the Portuguese, the Cantino planisphere does not describe trees in the parts of the Americas marked as Spanish. On the other hand, Newfoundland is adorned with tall trees and described as having “many masts.”

West Africa (detail),Cantino Planisphere, 1502, ink and pigment on vellum, 102 x 218 cm (Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena)

The only people depicted on the chart are in Africa. They include men and women and all but one are naked. The nearby text describing the purchase of enslaved people suggests that these represent people who have been or could be enslaved. By this time, the Portuguese were capturing Africans and selling them in Europe and to sugarcane plantations in the Madeira islands.

A dangerous heist?

The Cantino planisphere has long been described as an illegal copy of an official chart belonging to the Portuguese government where the newest geographic knowledge was recorded. This would have been a risky project since, according to a letter written by a Venetian living in Spain, giving foreigners information about new discoveries was punishable by death. Alberto Cantino wrote in a letter that he acquired the planisphere for the considerable price of twelve gold ducats. As a foreigner to Portugal, he was not supposed to obtain this kind of valuable geographic knowledge. Cantino smuggled the chart out of the country and presented it to his employer the Duke of Ferrara, Ercole I d’Este.

Recent research suggests that the chart’s creation was less dramatic. With the great numbers of charts, logbooks, and people traveling across oceans, the influx of information was immense and difficult to control. Pedro Reinel, the creator of several other surviving Portuguese charts, may have made the Cantino planisphere and would not have needed to sneak into government offices to do so. [1]

Cantino Planisphere, 1502, ink and pigment on vellum, 102 x 218 cm (Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena)

Long-lasting consequences

Although texts along shores mention local inhabitants, the chart presents the world as available for Europeans to claim and dominate. Ercole d’Este I likely had ambitions of gaining access to overseas lands for financial gain, and copies of the chart were made that add new information and modify which European powers are supposedly in control of which lands. This white supremacist ideology fueled colonization and enslavement for centuries to come, the consequences of which are still present today.