Approaching the entrance of the large complex known as the Colegio de San Gregorio in Valladolid, Spain, the surface seems to writhe with a dense entanglement of forms, making it challenging to read from afar. Only once you are near the doorway does it become easier to decipher the riot of ornament on this late 15th-century façade. Its impressive decoration is accentuated by the bare, massive walls of the building complex that surround it. The Colegio de San Gregorio is a religious complex—a Dominican colegio (a theological school or college) named after Saint Gregory (San Gregorio in Spanish).

Begun in 1498 by the artist Gil de Siloé, the entrance to San Gregorio epitomizes some of the inventive, complex architectural forms present on the Iberian Peninsula (today, Spain and Portugal). It is also considered the best example of Siloé’s style. Originally from northern Europe, Siloé spent most of his career in Spain, working in Burgos, Valladolid, and other cities. Some of his most important commissions were for Queen Isabel of Castile (one of the Catholic Monarchs) for the Miraflores Monastery near Burgos, where Siloé sculpted the retablo (altarpiece) and made several tombs, including one for Isabel’s parents, Juan II and Isabel of Portugal. [1] While not directly patronized by Isabel, Siloé’s façade for San Gregorio helped to communicate Castilian royal power through its iconography and even the fanciful way that he animated the surface.

The patron, Fra Alonso de Burgos

The colegio was founded in 1488 by the Dominican Friar Alonso de Burgos, one year before Siloé started the façade. Friar Alonso was the confessor of Queen Isabel (and had been prior to her becoming Queen), and held several other important positions and titles in the Church. He wanted to build a new colegio to train and educate young Dominicans and to gather some of the best artists of the day to construct and decorate it—all of which helped to advertise his own role in the colegio’s construction and to elevate his status. The façade, as the entrance to the larger complex, was one of the best ways to communicate these messages.

Let’s consider the façade more closely to see why it is considered visually inventive and how it conveyed power and status.

Articulated levels

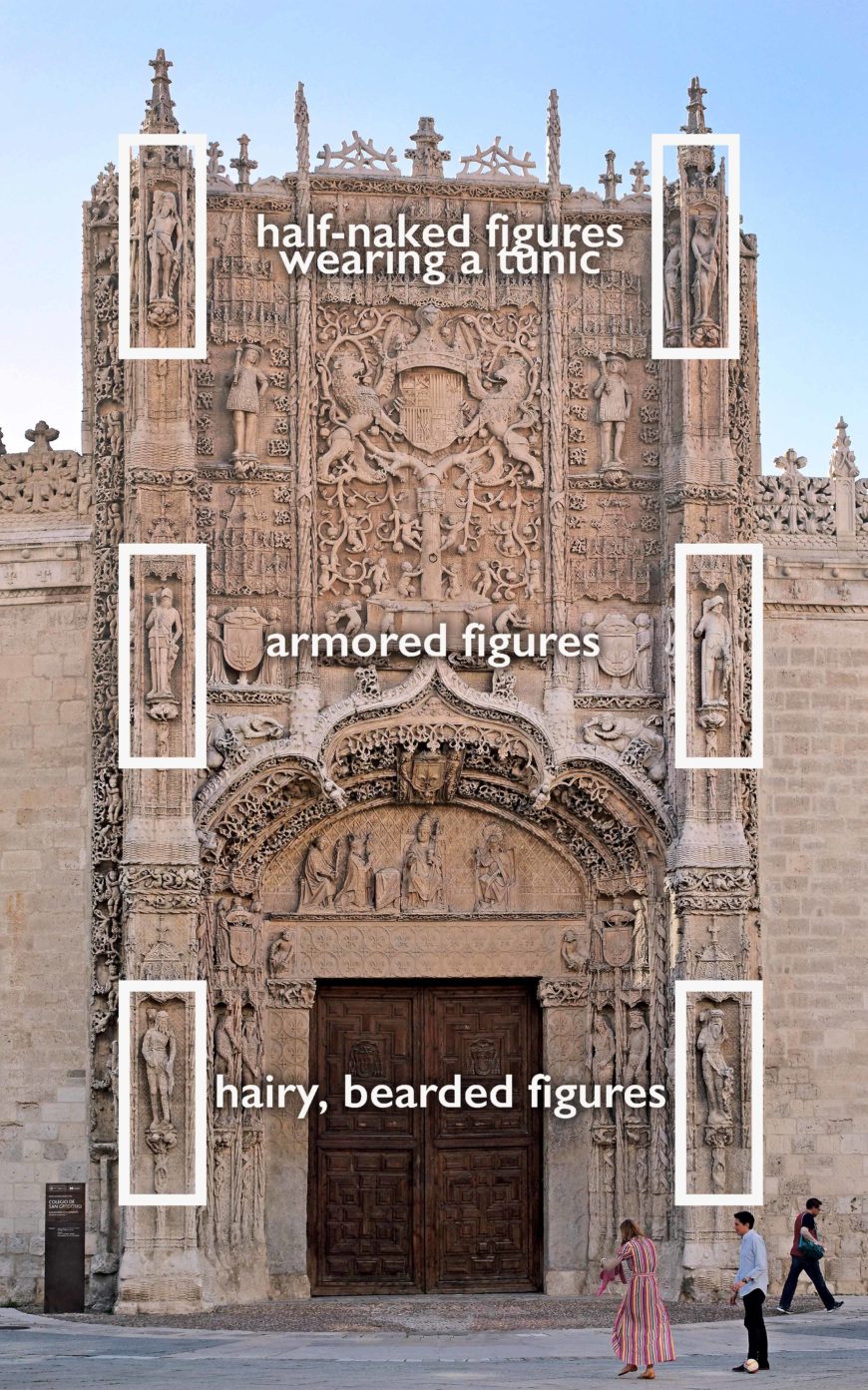

While at first glance the ornate façade seems to have no clear order, its logical organization becomes more obvious with close looking. The two buttresses are divided vertically into three levels of stacked pilasters. On the lowest level, the pilaster has hairy, bearded figures that are also on the doorway jambs. The second level shows male armored figures, complete with lances. The top level shows half-naked male figures in a tunic. It has been suggested that perhaps the levels refer, from bottom to top, to people who are uncivilized, civilized, and virtuous. It is not clear however, and the meaning could be different.

Between the buttresses, we have two clearly defined spaces, separated by the arch surrounding the doorway. The way that the façade is articulated makes it look like a retablo (altarpiece) in stone—and would have undoubtedly echoed the retablo (also made by Siloé) inside (now destroyed, but likely similar to his other one at the Monastery at Miraflores).

“Wild men” on the jambs of the Façade of San Gregorio, c. 1499, Valladolid, Spain (photo: Javi Guerra Hernando, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Hairy men

Flanking the door on the jambs are hairy, bearded men that hold shields and maces and stand on slim colonnettes. These figures—sometimes referred to as “wild men”—have been challenging to understand. One theory is that they connote humans in a less civilized time when people were perceived to have been more connected to nature. Some scholars have seen a possible parallel with Saint John the Baptist, who was bearded, wore a hair shirt, and lived in the wilderness; understood in this way, the hairy men would both literally and figuratively seem to support the colegio.

Other scholars have also posited that they may symbolize Indigenous peoples of the Americas, who were believed by Spaniards at this time to be inferior and less advanced than Europeans. Isabel and Ferdinand had financed Christopher Columbus’s voyage in 1492 that resulted in Europeans discovering that the world was much bigger than they believed and initiating waves of invasions and conquests of peoples and lands, and with conquest came Christian evangelization. According to this reading, the hairy men on the jambs and buttresses represent European tropes of less civilized peoples, such as Indigenous peoples, in the guise of so-called “noble savages,” which is positions someone as primitive, uncivilized, and as a romanticized “Other.” This trope is one that originated at this time and continued to develop over centuries. The façade’s beginning date of 1498 was only six years after Columbus first landed in the Caribbean and the ensuing collision of Europeans and Indigenous peoples had occurred; shortly after the invasion, artists began to invent images to show what they believed Indigenous peoples looked like based on stories and reports they heard and read. Against the backdrop of the early conquest of the Americas, the hairy figures (according to this theory) could have connoted a powerful message of Spanish and Church power. Still, it bears repeating that there is no scholarly consensus on these figures’ meaning.

Tympanum, on the Façade of San Gregorio, c. 1499, Valladolid, Spain (photo: GFreihalter, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Glorifying Friar Alonso

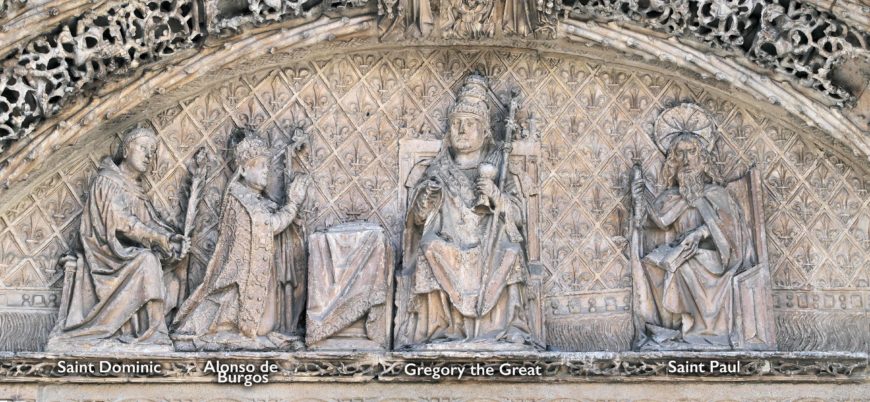

Above the doorway, in the tympanum, we see Friar Alonso de Burgos kneeling, his hands clasped in reverence, before Saint Gregory the Great who is seated on a throne and adorned with a papal tiara and crozier. By kneeling before the patron saint of the colegio, Siloé emphasized Friar Alonso’s humility and piety. Friar Alonso’s position also advertises his important role in the building’s construction.

Tympanum, on the Façade of San Gregorio, c. 1499, Valladolid, Spain (photo: Luis Fernández García, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The two other individuals on the tympanum are Saint Dominic (the founder of the Dominican Order) and Saint Paul, one of Christ’s apostles, who is shown wearing a cruciform halo (typically reserved for Christ). Dominic and Paul were also patron saints of a convent nearby. The land for the Colegio of San Gregorio had also been donated by the convent of San Pablo (Spanish for Paul), apparently because of the favors Friar Alonso had bestowed on it earlier—and a likely reason for Paul’s inclusion here on the tympanum. Framing the tympanum is an elaborate arch (what looks like a trefoil ogee arch that tapers upward to a point), accentuated with delicate tracery, which draws our attention to the doorway and tympanum—and thus to Friar Alonso.

Spandrels with figures fighting beasts above the tympanum, Façade of San Gregorio, c. 1499, Valladolid, Spain (photo: Rowanwindwhistler, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In spandrels above the tympanum, we also see figures fighting (or wrestling) with beasts, possibly meant to be lions; it is unclear who these figures are. It has been suggested that they could be Samson or Hercules—two figures that fought powerful lions, and in the 15th century both symbolized defense. Regardless of who these beast wrestlers are, their inclusion here is to symbolize their protection of the Church from any enemy—and by extension Friar Alonso and the Castilian monarchs as well.

Angels holding the fleur-de-lis above one of the spandrels, Façade of San Gregorio, c. 1499, Valladolid, Spain (photo: Rowanwindwhistler, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Fleur-de-lis are noticeable across the façade, in the jambs and tympanum, and in coats of arms, adding to the façade’s visual complexity. Friar Alonso had adopted the symbol as part of his personal emblem, so the symbol’s not-so-subtle use across the façade was another way to remind viewers of the role he played in establishing the building.

Top portion of the Façade of San Gregorio, c. 1499, Valladolid, Spain (photo: Jesusccastillo, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The royal coat of arms and the Tree of Life

The top half of the façade shows a complex tree, on top of which is a coat of arms held up by crowned lions. An eagle’s head rises from the top and projects outward, with its wings lifting upwards, talons grasping the sides, and tail feathers emerging below.

Top portion of the Façade of San Gregorio, c. 1499, Valladolid, Spain (photo: Jesusccastillo, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The coat of arms belongs to the Castilian monarchs, Isabel and Ferdinand. A common symbol of Saint John the Evangelist (one of the gospel writers), the eagle was used by Isabel and incorporated into the Catholic Monarchs’ coat of arms.

Top portion of the Façade of San Gregorio, c. 1499, Valladolid, Spain (photo: Jesusccastillo, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Rising below the coat of arms is a bounteous pomegranate tree, often identified as the Tree of Life, which emerges from a fountain. Branches hang heavy with fruit, angling downwards and twisting upwards around the coat of arms. Small playful putti (cherubs) surround the fountain. The pomegranate is an important symbol in Christianity, signifying Christ’s resurrection—a theological allusion appropriate to a Christian Dominican building. It is also possible that the pomegranate tree resonated with more contemporary events, specifically the Catholic Monarchs’ conquest of the Nasrid Kingdom in Granada in 1492. The pomegranate was an emblem of Granada (in Spanish, pomegranate is granada), and its appearance below the coat of arms could allude to Spanish power and the Nasrid defeat.

Amidst all these scenes and details are more figures and designs. To the sides and just below the Castilian monarch’s coat of arms and the tree, Fra Alonso’s coats of arms are held by pairs of angels (shown earlier). Once again, the friar and royals are visually connected. Above and directly alongside the lions protecting the monarchical coat of arms are two soldiers (seen above)—once again, symbols of protection.

No space is left unadorned. Elaborate tracery, scrolling vines, textile and lace-like patterns, angels, ribbons, grotesques—what isn’t on this façade?

What style is this façade?

Detail of the exterior of the Casa de las Conchas, 15th century, Salamanca, Spain (photo: Luis Rogelio HM, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Covered chalice, late 15th century, silver, gilded with rubies, sapphires, diamonds, and crystals, made in Toledo, Castile-La Mancha, Spain, 43.7 x 19.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The style of the façade has been described as Isabelline (also sometimes called Gothic-Plateresque or Hispano-Flemish), which refers to an architectural mode favored during the reign of the Isabel and Ferdinand and that forms the basis for a style called the Plateresque. Overall, the so-called Isabelline and even Plateresque is a combination of different elements and forms, but in general there is a preference for decorative surface patterning or what art historian Ethan Matt Kavaler calls an “intentional excess,” such as we see on San Gregorio’s façade or other late 15th-century buildings such as the Royal Chapel of Granada and La Casa de las Conchas in Salamanca. [2]

We find this complex decoration in silver and gold objects, suggesting a translation of a shared visual language into stone. (Silver objects would also increase in production and popularity after silver was discovered and mined in the Spanish-controlled Americas.) This preference for intertwining, complex surface decoration is also similar to earlier Iberian objects and architectural elements, attesting to the challenge at attempting to pinpoint one specific source for the so-called Isabelline style. Iberia was home to many different cultural traditions that borrowed and adapted from one another over time.

San Gregorio’s façade has been described as combining Gothic, Italian, Flemish, and Mudéjar elements, and sometimes even Roman or classical elements—but what does this mean? And does it matter? Spanish art of this time more generally has been described as eclectic (less purely one “thing”), decadent, or lacking in overt classicizing features—and so it has been characterized as inferior or has been overlooked in favor of other 15th-century architectural developments outside of Iberia. [3] It seems to me that trying to impose one specific stylistic label (or labels) does a disservice to the creative imagining of intentionally excessive forms across this building’s surface.

What we can say about the façade is that it represents a wildly inventive visual vocabulary on a building whose patron had connections to the Catholic Monarchs (Ferdinand and Isabel)—and who wanted to surely be remembered for his role in the development of this Dominican center of learning.