Sir Joshua Reynolds, Mrs. Siddons as the Tragic Muse, 1783–84, oil on canvas, 239. 4 x 147.6 cm (The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens)

“The Tragick Muse”

“Ascend upon your undisputed throne, and graciously bestow upon me some grand Idea of The Tragick Muse.”Joshua Reynolds to Sarah Siddons in his studio [1]

The most emblematic of Sir Joshua Reynolds’s celebrity portraits of women is Mrs. Siddons as the Tragic Muse. Siddons was one of the first women to play Hamlet—she did so 9 times over 30 years, doing it while cross-dressing, without ever wearing “sexualized” tight-fitting male breeches. Of the more than 400 or so portrayals of the famed Welsh-born British theater actress and cultural icon Sarah Siddons (née Kemble), it is Reynolds’s large-scale allegorical portrait which was, and remains, the most acclaimed. This is because it was a watershed work of art for both the sitter and the artist. It elevated the profession of acting, the status of the actress, and the fame of Siddons; it also elevated the reputation of Reynolds, and raised the status of portrait painting to that of heroic history painting at The Royal Academy of Arts exhibition in London of 1784, where it stole the show according to the vast majority of the critics. One commentator lauded it as, “a most sublime and masterly Performance.” [2] Identified in the exhibition catalogue as, “Portrait of Mrs. Siddons, whole length,” it was the critics who re-titled it Mrs. Siddons in the Character of the Tragic Muse.

The painting depicts a majestic and dramatically lit Siddons, seated on a cloud-borne throne as Melpomene, the classical personification of Tragedy, one of the nine Muses of the arts (the ancient Greek poet Hesiod records that they were the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, or “Memory,” who provided inspiration to poets and musicians and those involved in the creative arts). The diadem, puffed-out hairstyle, fanciful opulent gold dress, and the fat-knot of looped pearls at her bosom, underscore her noble, almost queenly standing. In 1827, the portrait painter Sir Thomas Lawrence spoke of the painting in his Presidential Address to the students of The Royal Academy of Arts as, “indisputably the finest female portrait in the world.” [3]

Detail of Sir Joshua Reynolds, Mrs. Siddons as the Tragic Muse, 1783–84, oil on canvas, 239. 4 x 147.6 cm (The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens)

“The passions of the soul”

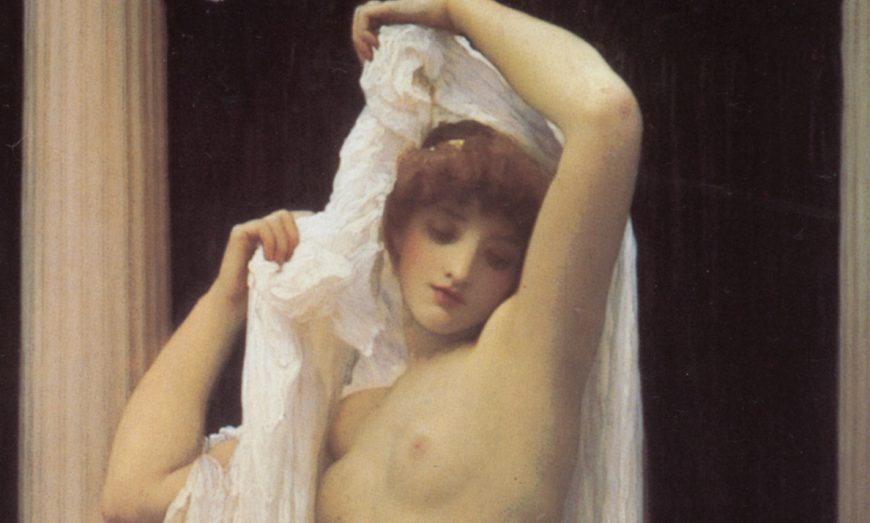

We view Siddons from below. Her head is turned away from us, tilted upwards to the left, which accentuates her famous countenance—“Damn the nose—there’s no end to it!” the painter Thomas Gainsborough reportedly once remarked. Her right arm is flopped in passive resignation, while her left arm is erect in active anticipation; her left index finger is half raised as if to signal that she is about to speak. Behind her, she is flanked by two disquieting spectral allegorical figures: to her right, the forlorn-looking figure of Pity, with downcast eyes, who holds, droopily, a bloody dagger; and to her left, the grim-visaged figure of Terror, eyes wide and feral, who proffers a poisoned cup or chalice, whose shrieking Medusa-like face is partly modeled on a drawing Reynolds did of his own howling face in contortion while looking in a mirror.

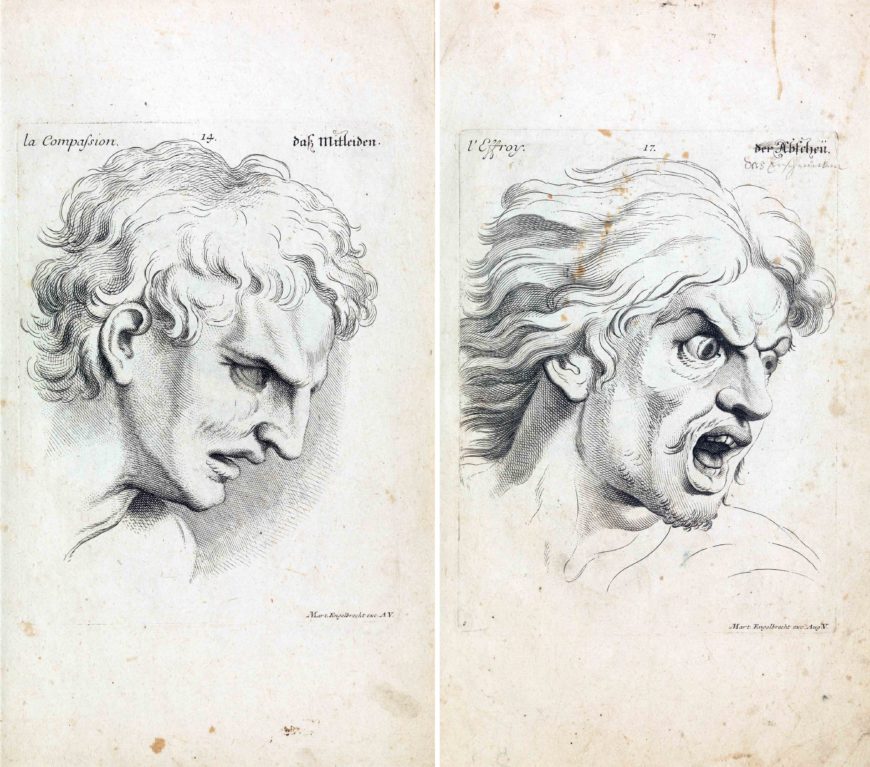

Jean Audran, after Charles Le Brun, La compassion (“compassion”) and L’effroy (“terror” or “fright”), in Expressions des passions de L’âme, 1727, engraving with etching, 247 x 191 and 253 x 195 mm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Otherwise, the two faces of Pity and Terror seem to originate from those of Compassion and Fright illustrated in Charles Le Brun’s Les expressions des passions de l’ȃme (“The expressions of the passions of the soul”, 1727), a treatise on the theory of expression and pathognomics (the theory of the physical effects of the “passions” [“emotions”] “of the soul” on the muscles of the face and on the eyebrows), which was based on a famous lecture, first delivered in 1668 at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris. Le Brun’s work was translated and disseminated throughout Europe, and was hugely influential on painting and acting in eighteenth-century Britain. Reynolds would have taken the faces from John Williams’s English translation A Method to Learn to Design the Passions (1734).

Aristotelian tragedy

Pity and Terror (usually known as Pity and Fear) are the twin emotions or passions which are aroused through the imitation or representation (“mimesis”) of incidents of tragedy in drama (according to Aristotle’s Poetics), so that the audience or reader might be vicariously “purged from,” or “purified of,” these emotions. This is known as “catharsis,” a metaphor whose precise meaning has been endlessly debated due to its ambiguity in Aristotle’s text. It can be interpreted, however, as the paradox of “tragic pleasure” at witnessing or reading the trials, tribulations, and (deserved) tragic end of a flawed hero (or heroine), at which the audience or reader experiences either a satisfying emotional release through a cleansing of the emotions (they are brought to the fore, and then flushed out), or a sense of enlightenment through the attainment of a right balance and an understanding of those emotions via a clarification of them. Whether understood at a psychological, or an intellectual, or a moral, or an aesthetic level, tragedy is thus a pleasurable, transformative, and liberating experience.

The dagger and poisoned cup

The attributes of the dagger and poisoned cup or chalice signify not only the Muse of Tragedy, but also recall, and foreshadow, Siddons’s signature performances as William Shakespeare’s ambitious, ruthless, and tormented character of Lady Macbeth, a character which Siddons sensationally reinvented as a beautiful multivalent tragic heroine, rather than following in the footsteps of the well-established theatrical tradition of essentializing her as a “fiend-like queen, ”as Lady Macbeth is referred to in the play itself. Up until this point the tragic hero of the play had been considered to be the man, Macbeth.

From “fiend-like queen” to “tragedy personified”

In Shakespeare’s play Macbeth (written in 1606; published in the First Folio in 1623), Lady Macbeth induces her husband Macbeth, a Scottish general, to kill the king in order to seize the crown of Scotland. The plan is for Macbeth to kill the sleeping King Duncan with the daggers of the king’s two grooms (guards or officers), in order to incriminate them in the murder. To this end, Lady Macbeth drugs the “possets” (nightcaps of eggnog mixed with wine) of the grooms. However, after murdering the king, Macbeth is so overcome with terror by what he has done that he is too afraid to plant the evidence on the grooms, so it is left to Lady Macbeth to take the bloody daggers and “gild the faces of the grooms” with blood. This deception is successful, and, fearing for their lives, the sons of King Duncan flee the country and the Macbeths become king and queen of Scotland. Many further murders ensue to secure their position. Consequently, psychologically riven, racked with guilt, and suffering from night-terrors, Lady Macbeth finishes the play off-stage at her own “violent hands” (so Shakespeare suggests to us).

George Henry Harlow, Sarah Siddons in the Scene of Lady Macbeth Sleepwalking, 1814, oil on canvas, 64 x 39.4 cm (London, Garrick Club)

Although Siddons had played the role of Lady Macbeth in the English provinces (in Cheltenham, and to plaudits at the Theater Royal, Bath, in 1779) before Reynolds painted his portrait, it was not until 1785, the year after the exhibition of the painting at The Royal Academy of Arts, that she acted the part of Lady Macbeth for the first time on the stage in London, at Drury Lane. The response of the public and the critics alike was nothing less than rapturous. She is remembered definitively for the startling innovation of placing the candle down in the sleepwalking scene (actresses had up until that point carried the candle throughout the scene), as immortalized in George Henry Harlow’s portrait, so that she could wring her hands from the imaginary blood which had stained Lady Macbeth’s unconscious mind, and soul; a scene which the essayist, critic, and painter William Hazlitt described, thus:

In coming on in the sleeping-scene, her eyes were open, but their sense was shut. She was like a person bewildered and unconscious of what she did. Her lips moved involuntarily—all her gestures were involuntary and mechanical. She glided on and off stage like an apparition. To have seen her in that character was an event in every one’s life, not to be forgotten. [4]

Hazlitt wrote this after Siddons had retired, had given countless performances as Lady Macbeth, had honed her skills at achieving the role’s emotional complexity and tension, and had drawn out a dignity and pity for her character as a tragic or fallen heroine (a loyal and devoted wife, possessed of a lofty grandeur, and an over-weening lust for power, who has suffered, and whose conscience ultimately torments her to death). Given this, Hazlitt’s views of her portrayal of Lady Macbeth had been fundamentally defined by Reynolds’s evocative portrait, when he effused:

In speaking of the character of Lady Macbeth, we ought not to pass over Mrs. Siddons’s manner of acting that part. We can conceive of nothing grander. It was something above nature. It seemed almost as if a being of superior order had dropped from a higher sphere to awe the world with the majesty of her appearance. Power was seated on her brow, passion emanated from her breast as from a shrine; she was tragedy personified. [5]

Michelangelo, Isaiah, detail of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1508–12, fresco (Vatican City, Rome)

Artistic sources

Domenico Zampieri, called Il Domenichino, Saint John the Evangelist, late 1620s, oil on canvas, 259 x 199.4 cm (London, National Gallery, on loan from a private collection)

Stimulated by a range of literary and visual sources, including, for example, William Russell’s poem The Tragic Muse: A Poem Addressed to Mrs Siddons (1783), the painting pays, in part, pictorial homage to the “Grand Manner”/“Grand Style” (this term refers to idealized form which transcends Nature) and terribilità (“terrifying intensity” and awe-inspiring nature) of the works of Michelangelo through the free adaptation of the position of Michelangelo’s figure of the Prophet Isaiah on the Sistine Chapel Ceiling.

The pose of Siddons may also be derived (in reverse) from Domenichino’s baroque masterpiece Saint John the Evangelist; and it reveals the distinct influence of the brushwork of Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn, in its magical light and dark effects, and the use of a limited and sober palette of colors of yellows and golden browns with orange highlights, all in warm tones, applied thickly. However, as reminisced by Siddons herself (so we should take it with a pinch of salt), the pose may owe to her own spontaneous response to Reynolds’s request for her to act the part: “I walked up the steps, & seated myself instantly in the attitude in which She now appears. This idea satisfyd him so well that he, without one moments hesitation, determined not to alter it.”

Theatrical inspirations

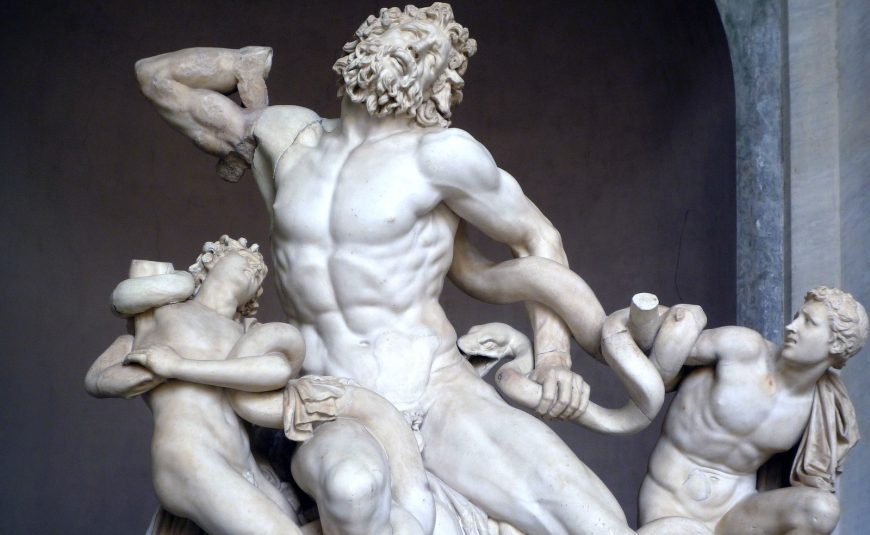

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums)

More than this, the painting might be taken as an object lesson in the changes afoot in the acting technique of the later eighteenth century, which Siddons did much to spearhead. She went beyond the formulaic, rhetorical style of acting, made famous by the actor-manager David Garrick and others, which worked through a system of “points”, i.e. set positions or postures, gestures, and calculated facial expressions the actor or actress had to make on stage to convey particular emotions and feelings, many of which were inspired by well-known works of art. To express horror, for instance, actors and actresses turned for instruction to the ancient late Greek Hellenistic sculpture Laocoön and his Sons, and the “cry” on the face of Laocoön.

Instead, Siddons strove to achieve more fluid emotional intensity in her acting, to express multiple emotions in one facial expression, and to stir the audience to have the same feelings as her character on stage, to which ends it is said that she directed her own private woes—an unhappy marriage and outliving five of her seven children—into her public performances.

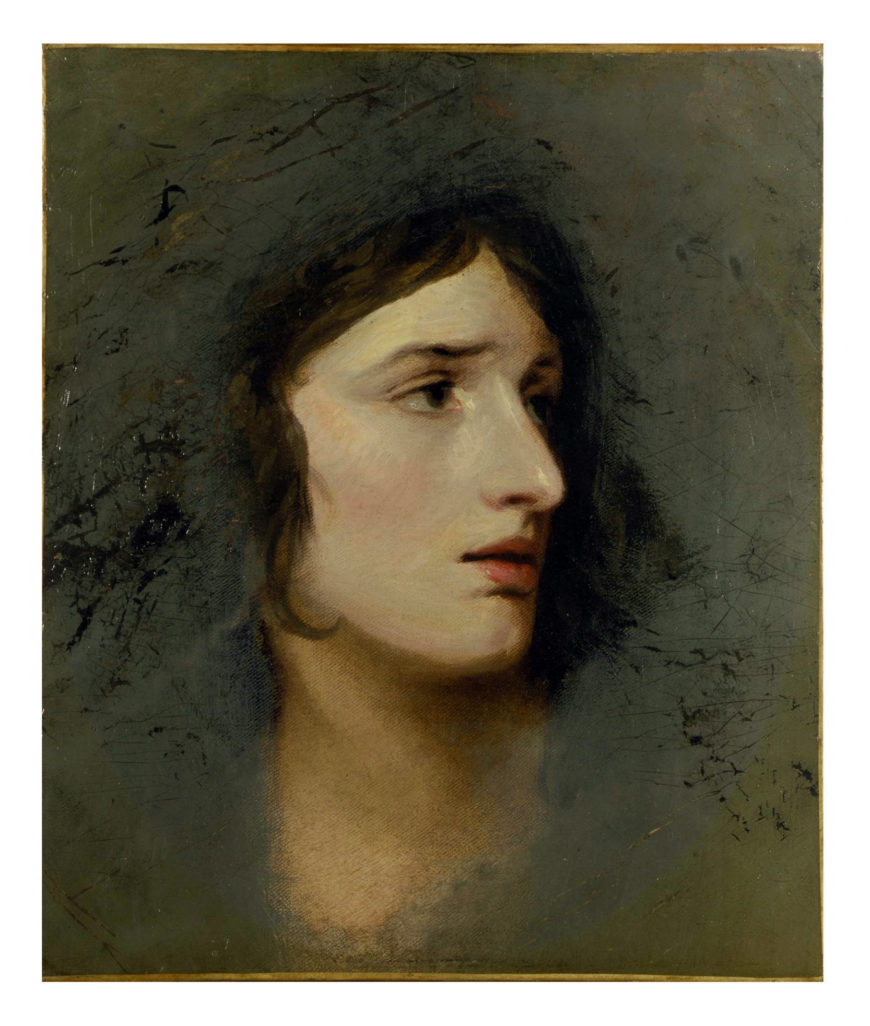

William Hamilton or Thomas Beach, Portrait of Sarah Siddons, c. 1784, oil on canvas, 34 x 28.6 cm (Victoria and Albert Museum)

We can get a vivid sense of this more nuanced, and empathic, method of acting, and its moving charge, by looking at a close-up of Mrs. Siddons as the Tragic Muse in conjunction with an exquisitely affecting life-size oil sketch of Siddons’s profile which was completed around 1784 by either William Hamilton or Thomas Beach, and narrates either Zara, the protagonist of William Congreve’s tragedy The Mourning Bridge, or Lady Macbeth at the point when she takes the bloody daggers from a petrified Macbeth. Both close-ups reveal a subtlety, complexity, and hybridity in Siddons’s facial expression, caught, as it were, among fear, anguish, melancholy, despair, and guilt—emotions which could be said to convey the vulnerability, fragility, and suffering of Siddons’s innovative interpretations of Lady Macbeth. It would be intriguing to know what tragic personal experiences or public performances Siddons could have been tapping into at the time. We might surmise that she was rehearsing her transitional faces of Lady Macbeth here. It is this more sophisticated, naturalistic, and intensely felt approach to acting technique which led to Siddons becoming widely hailed as the greatest tragedienne of her age.

Absolutely awesome

In picturing Sarah Siddons as the Muse of Tragedy, evoking and prefiguring her historic performances as a tragically heroic Lady Macbeth, and possibly celebrating the complexity of her acting technique, Sir Joshua Reynolds helped make an argument for women’s equal standing with that of men within the acting profession, a profession which David Garrick had been all too keen to see raised to the heights of respectability. In Reynolds’s painterly hands and Siddons’s aristocratic attitude, the actress had been elevated to a well-nigh transcendental realm far above that of the earth-bound “respectable courtesan” which she had inhabited in the past.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Mrs. Siddons as the Tragic Muse, 1783–84, oil on canvas, 239. 4 x 147.6 cm (The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens)