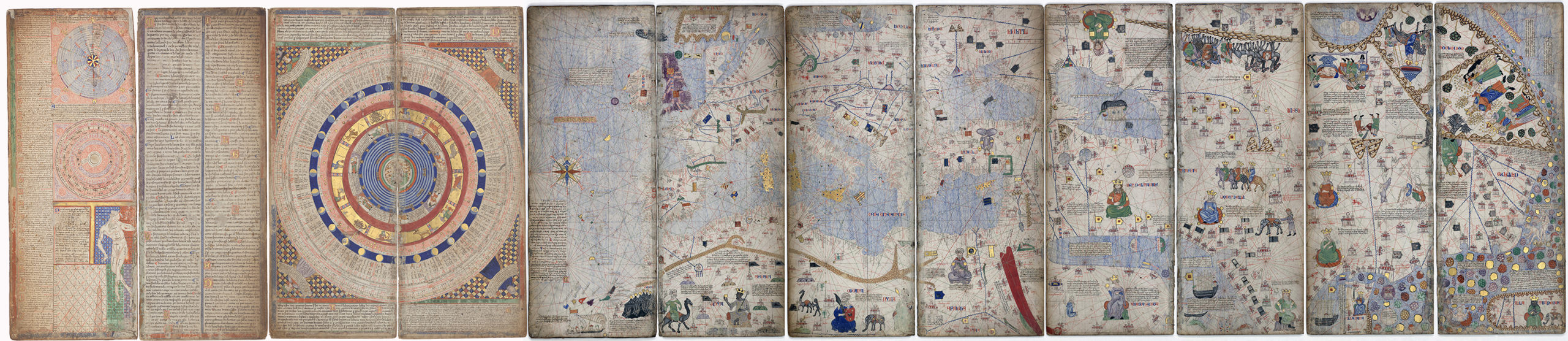

Catalan Atlas, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1375, Majorca, 25.3 x 118.1 inches (Bibliothèque Nationale de France). (For annotated images see Panels 1-2, Panels 3-4, Panels 5-6)

What did Europeans know of the geography, politics, and peoples around the globe in the late 14th century? A celebrated Jewish mapmaker in Majorca, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, with his knowledge of Catalan, Hebrew, and Arabic, visualized his conception of the universe and the inhabited world in his remarkable 1375 Catalan Atlas. Measuring nearly ten feet in width and spread across six parchment leaves mounted on wooden boards, the map he created represents the height of medieval mapmaking in Majorca—an island off of the eastern coast of the Iberian peninsula (today Spain and Portugal) and a territory of the Crown of Aragon, which, in the 14th century, dominated much of the Mediterranean basin.

Combining various approaches to mapmaking, Cresques created a visual encyclopedia of the world, containing extensive commentary in captions and images designed to encompass all known geographical, historical, and human knowledge. In its ambitious geographic scope, covering lands from the Atlantic to China and from Scandinavia to Africa, the Catalan Atlas presents a highly connected medieval world. By examining the imagery of his Catalan Atlas, we can see how one 14th-century Jewish man understood the political and ethnic realities of his world.

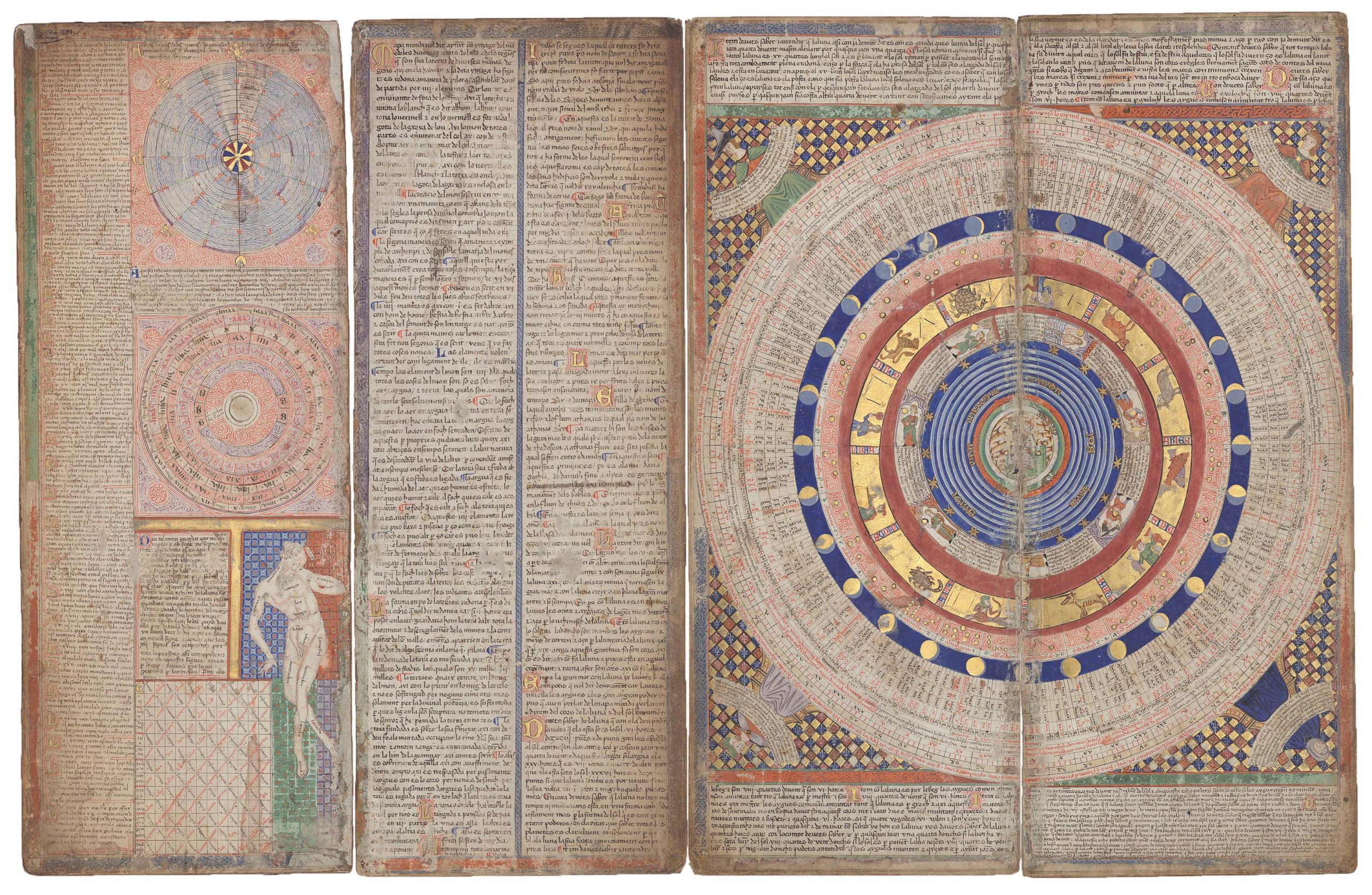

Panels 1 and 2, Catalan Atlas, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1375, Majorca (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

The map’s rich and colorful imagery are exceptionally well-executed; it is not surprise that Cresques, a gifted painter and scribe, worked as the mapmaker to the King of the Crown of Aragon. In fact, he was the only mapmaker of his generation known and documented in the service of the Crown, and his Catalan Atlas was likely a royal commission by King Peter IV of Aragon possibly as a gift to King Charles V of France. [1] The images in the map are oriented in every direction, suggesting that the Atlas would have been prominently displayed on a table to be seen from all sides when viewed by the king and his privileged guests. The Catalan Atlas served as a visualization of the King’s power and worldview. As expected, Cresques imbued the map with the desires of his royal patron, but if we look closely we see that he imbued it with his own worldview as well.

A visual encyclopedia

The first two panels of the Catalan Atlas (see above) contain lengthy texts and diagrams charting contemporaneous scientific knowledge of the universe. The content of these panels belongs to a genre of popular astronomy and astrology, known throughout Europe, including charts of the days of the month, systems for determining the course of the tides, and models for calculating the dates of Easter and other Christian holidays. Although this data was compiled by Cresques from Islamic and Jewish astronomical and astrological treatises, they were not intended for practical use. For its royal patron, they instead present a vision of an organized cosmos—a reflection of his stable rule.

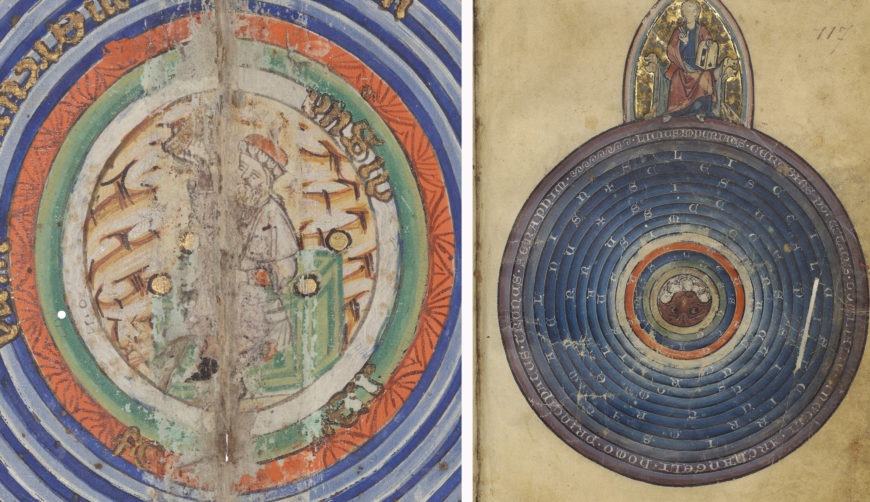

Left: seated scholar with quadrant, Catalan Atlas (Sheets 2A-B), Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1375, Majorca (Bibliothèque Nationale de France); right: Christ in Majesty presiding over the earth at the center of the spheres of the universe, Gossuin de Metz, L’image du mode, 13 century (Bibliothèque National de France)

At the center of Sheet 2, we see a much-damaged rendering of a seated scholar holding a quadrant. Surrounding him are richly colored concentric circles featuring calendars of the sun, moon, planets, seasons, and the zodiac. This calendar-wheel, along with the accompanying texts and diagrams on Sheet 1, convey a sense of an ordered and structured universe. This diagram echoes contemporaneous representations of the cosmos, but crucially departs in the rendering of the seated scholar. Whereas most medieval manuscripts, as in a thirteenth-century copy of Gossuin de Metz’s Image of the World, often depicted the universe within a Christian worldview, showing God as creator, overseeing and protecting the world, in the Catalan Atlas, God is absent. In God’s place, sits a man with his quadrant, emphasizing that through study and scholarship comes knowledge and power. These introductory panels provide a framework for and a fitting opening to the map of the inhabited world which follows, one befitting its royal patron and audience.

Medieval maps: Visualizing the world

Maps can tell us about the way people conceive of the world around them. They are not merely navigational tools, but also cultural documents, expressing in visual form their owners’ imagination and knowledge of the world. To understand the significance of Cresques’s Catalan Atlas, we first need to look at mappaemundi (literally, cloths or charts of the world), medieval European maps which typically portrayed the world through a Christian lens to reflect the perfection of God’s creation and chart the history of human salvation, both in space and time.

The Map Psalter, 1262–1300, London or Westminster, England (The British Library)

Let’s take, for example, a late thirteenth-century map included within a psalter. The world map prominently places the city of Jerusalem—considered especially holy as the site of Jesus’s crucifixion and resurrection— at the center of the depicted world. The faces of Adam and Eve appear ensconced in the earthly paradise, the Garden of Eden, on an island at the top of the map. The biblical whale that swallowed the prophet Jonah swims in an ocean while Noah’s ark rests atop Mount Ararat.

Gazing over the world, Christ stands flanked by angels. He raises his right hand in a gesture of blessing while in his other hand he grasps a small globe of the world—a sphere resembling a T-O map of the world. With Christ presiding over the world below him, the represents the totality of human history from the Garden of Eden to the Heavenly Jerusalem.

Portolan chart attributed to Angelino Dulcert, mid-14th century (British Library)

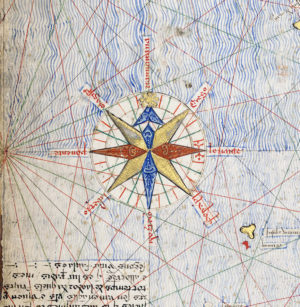

This religious worldview is absent from Cresques’s Catalan Atlas. Not only does Cresques remove the image of God and most biblical scenes from the cosmological charts and the map itself, but further breaking with medieval conventions for creating a world map, he modeled his Atlas on rectangular portolan charts, nautical maps used by sailors for coastal navigation and maritime exploration. With their attention to detail, portolan charts aided Cresques in rendering regions of the world well-traveled and documented by Europeans (such as the territories surrounding the Mediterranean Sea). As in portolan charts, a complex web of lines called windrose lines (or rhumb lines) crisscross the Atlas. Likewise, coastlines are densely populated with city names. The Catalan Atlas stands out for its geographical realism, accuracy, and the sheer amount of data included.

Compass rose and windrose lines, Catalan Atlas (Sheet 3A), Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1375, Majorca (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

To define landmasses and fill in the details of more distant territories not yet been mapped in portolan charts or explored as extensively by European travelers, Cresques relied on other Hebrew and Arabic sources. Living in the medieval city of Majorca (then a multilingual and multi-religious society populated by Christians, Muslims, and Jews), Cresques was well-positioned to work across these languages. Moreover, along with access to the library of his royal patron, through ongoing connections between the Jewish populations of Majorca and nearby North Africa, Cresques was likely also able to seek out resources in the cultural arena of the Maghreb. He was not only fluent in Occitan (the language used in Catalonia and Majorca), but he was also fluent in Hebrew, and likely also in Arabic. As a result, he could turn to travel narratives written by Europeans (such as the 13th-century journey of Venetian merchant and explorer Marco Polo along the Silk road), as well as rely on Arabic sources, such as the riḥla (travelogue) of Moroccan-born Muslim traveler Ibn Battuta in the lands of Afro-Eurasia in the 14th century. He further utilized Arabic geographic and scientific treatises and maps produced by Arab cartographers. Cresques’s use and placement of Arabic city names as well as the spatial organization of his map suggest that he had access to the world map created by famed Arab cartographer Muhammad al-Idrisi.

Despite this multicultural atmosphere, over the course of Cresques’s life, the Jewish community of Majorca and across the Iberian Peninsula faced increasing harassment, persecution, and at times forced conversion. These challenges shaped the way Cresques viewed and chose to represent the world around him in his Atlas.

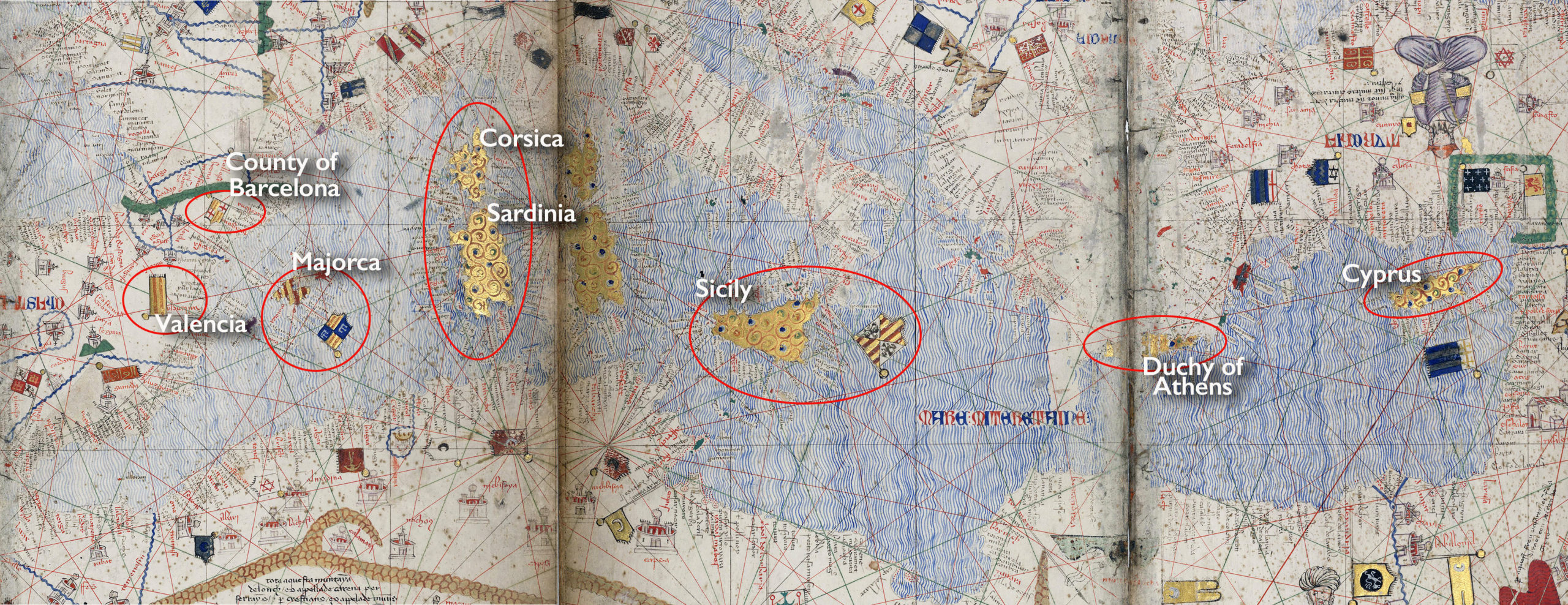

Representing the patron’s power: the Crown of Aragon

Given that his patron was the King of Aragon, it comes as no surprise that Cresques emphasized the Crown of Aragon’s spheres of political and commercial influence. Since their rise to power in the mid-thirteenth century, the Aragonese pursued a policy of maritime expansion. By the 14th century, they controlled much of the central and western Mediterranean basin, including modern-day northeastern Spain, the islands of Majorca, Sicily, Minorca, Ibiza, and Sardinia, as well as southern Italy up to Naples and parts of Greece and Asia Minor. Although never truly unified as a single entity, these territories were loyal to the Crown of Aragon.

The Crown of Aragon, Catalan Atlas, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1375, Majorca (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

On the Catalan Atlas, Aragonese-ruled territories are marked using the gold and ruby senyera (the Catalan flag) which often appears larger and more prominent than other flags on the map. The island of Majorca, the home of Abraham Cresques, is entirely colored with the senyera, creating an impression of a powerful political presence. Likewise, the large islands of the Mediterranean under Aragonese sovereignty are also distinguished in their ornament, marked entirely in gold with disk and scroll patterns in green, blue, and red. Together, the senyera and the gold-ornamented islands give the impression of a unified Mediterranean dominated by Aragonese political and commercial interests, an image that would have particularly appealed to the Atlas’s patron.

Ruler portraits from left: nameless Ottoman ruler in Anatolia (Sheet 4B); Jani Beg (d. 1357) of the Jochid Mongol Khanate (Sheet 5A); Queen of Sheba (Sheet 5A). Catalan Atlas, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1375, Majorca (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

Ruler portraits: documenting power and race

Moving south and east from the Mediterranean, into Africa, and West and East Asia, Cresques again diverged from earlier medieval maps by populating his map with images of rulers. Although often described as portraits, these images are not accurate renderings of the historical individuals, but visual markers of distinct political groups. The rulers are shown using a combination of royal imagery popular in European visual culture, such as scepters and crowns, and costumes and attributes more commonly seen in Islamicate imagery, such as turbans and cloth headcoverings, robes ornamented with tiraz armbands, and attributes such as a sword or shield. Contemporaneous European texts often characterized the Islamic world and its non-European, non-Christian rulers not only as exotic and different, but also as threatening enemies. For the patron of the Catalan Atlas, Peter IV of Aragon, the Islamic world was associated with the centuries-long enemy of the Reconquista and the Crusades, or with new rising threats, such as the emerging Ottoman power. However, through the use of European and Islamicate royal vocabulary, the rulers are rendered not as foreign or menacing, but rather as respected, powerful, and prosperous political rivals.

Africa south of the Atlas Mountains (Sheets 3A-B, 4A), Catalan Atlas, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1375, Majorca (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

Mansa Musa (Sheet 3B), Catalan Atlas, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1375, Majorca (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

Perhaps the most famous ruler portrait in Cresques’s map Mansa Musa, is the 14th-century ruler of the Mali Empire known for its abundant resources in gold. In 1324, 50 years prior to the production of the Catalan Atlas, Musa embarked on the hajj, traveling throughout the Islamic lands of West Asia. During his journey in Cairo, Mecca, and Medina, he spent so much gold that the overall value of gold decreased in Egypt for over ten years, causing severe inflation and crippling the local economies.

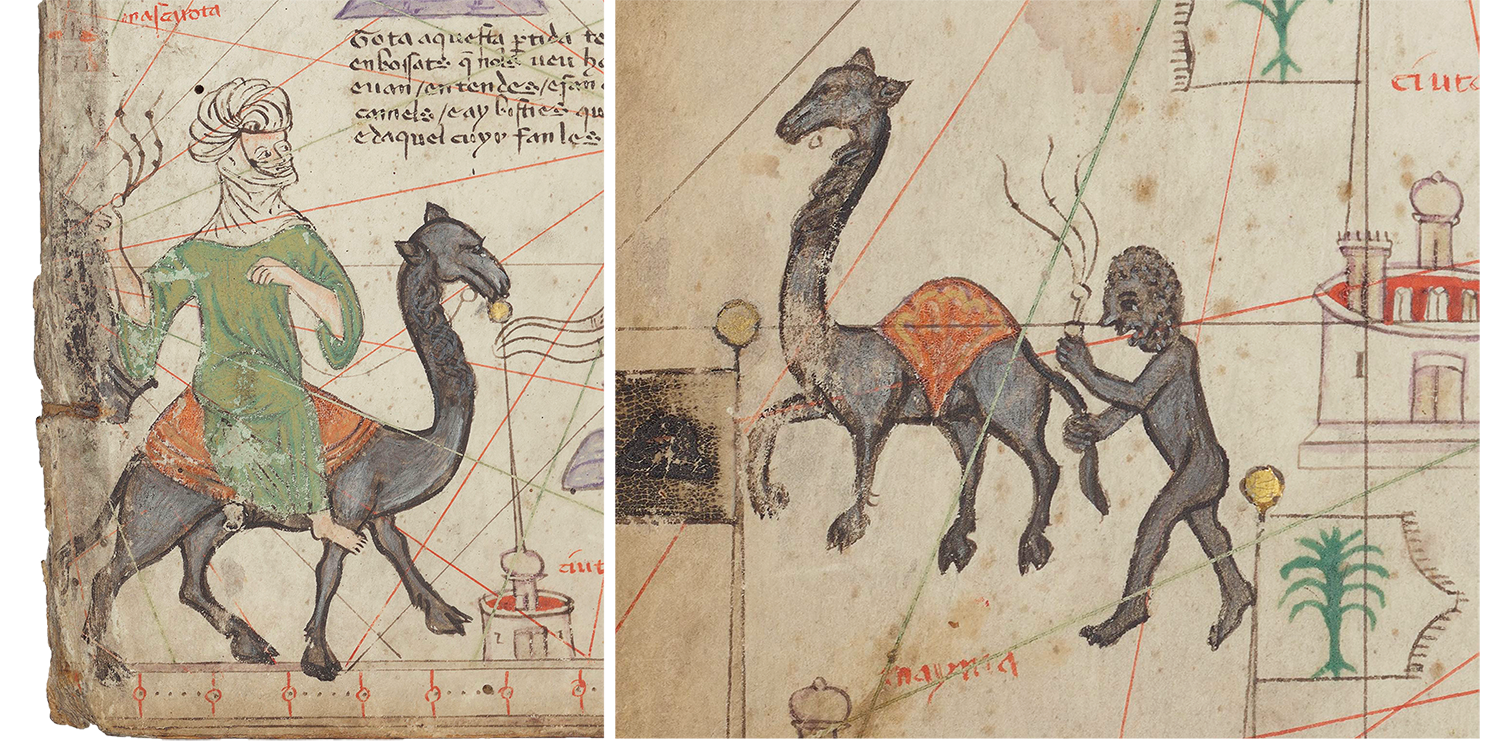

Whereas Africa often appears on the margins of medieval European maps, Cresques’s depiction of Mansa Musa represents Africa as a powerful economic center. He is shown seated cross-legged atop a cushioned, golden throne, and he wears a golden crown and carries an orb and scepter, traditional emblems of medieval European kings. A turbaned nomad riding on a dromedary approaches Mansa Musa, who gazes at him and extends a piece of gold in his hand, a monetary transaction reinforced by the golden adornments on the nomad’s tents.

Nomad and his tents (Sheets 3A-B), Catalan Atlas, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1375, Majorca (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

Together, they highlight the pivotal role played by the region of Mali in trans-Saharan trade. Since antiquity, networks of exchange had connected Africa and Europe, with commerce in gold and other materials bringing inhabitants of both continents into frequent contact. Gold mined south of the Sahara, along with salt, ivory, and enslaved peoples, was transported to the north by caravans of Saharan traders, reaching the shores of the Mediterranean and its maritime trade networks. The Catalan map pays special attention to this area of trade in both images and written legends, noting not only the abundance of gold, but also knowledge of the region’s fertile soil, settlements along caravan routes, and the production of leather goods.

The Muslim jouster’s blue skin and sneering expression make him appear not only foreign, but also monstrous. Luttrell Psalter, jousting scene between Muslim leader Salah al-din and English crusader King Richard I325–40 (British Library)

The imagery of Mansa Musa and the Saharan camel-traders also visualizes 14th-century European notions of race and cultural difference. While skin color could denote geographical regions known or believed to be inhabited by Black people, color symbolism in medieval imagery was predominantly tied to Christian theology, whereby lightness or brightness was associated with virtue, and darkness with sin. For example, during the Crusades, a period of increased anti-Muslim sentiment, Muslims were frequently depicted as dark-skinned by European artists, despite the fact that most Muslims they encountered would have had medium or light complexions. Rather than physiognomic accuracy, color denoted a perception of violence and religious error. In contrast, the majority of the rulers depicted in the Catalan Atlas are shown with fair skin, as political rivals of the Atlas’s patron, but not necessarily as monstrous others. The light complexion of the Muslim rulers as well as accompanying legends praising them as great and powerful may also have related to Cresques’s own positive associations with Islamic culture.

Left: Nomad, Catalan Atlas (Sheet 3B), right: Black African camel trader, Catalan Atlas (Sheet 4A), Catalan Atlas, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1375, Majorca (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

In contrast, the representation of Africa denotes Cresques’s keener awareness with respect to geopolitical diversity and racial difference. The image of King Mansa Musa, although employing common features of European stereotypes of Africans, including tightly curled hair and beard, a low-bridged nose, and full lips, appears mostly to mark geographical distance (rather than blackness as an exotic other). However, in his rendering of the adjacent figures (the nomadic rider to the left and a camel-trader to the right), Cresques’s image takes on a more insidious tone. On the one hand, the distinction between the light skin of the nomadic North African tribes and the dark skin of the Black African camel-trader from further south, suggests accurate knowledge of the region, likely drawn from contemporaneous Islamic maps and treatises. At the same time, the depiction of the black-skinned camel-trader renders the figure as primitive. Represented with his mouth ajar and nude (both often associated in medieval art with barbarism or sexual sin), the figure embodies racist interpretations found in some contemporaneous Islamic and Jewish texts. Perhaps such an image would have promoted Africa as a region ripe for colonization to its Aragonese patron.

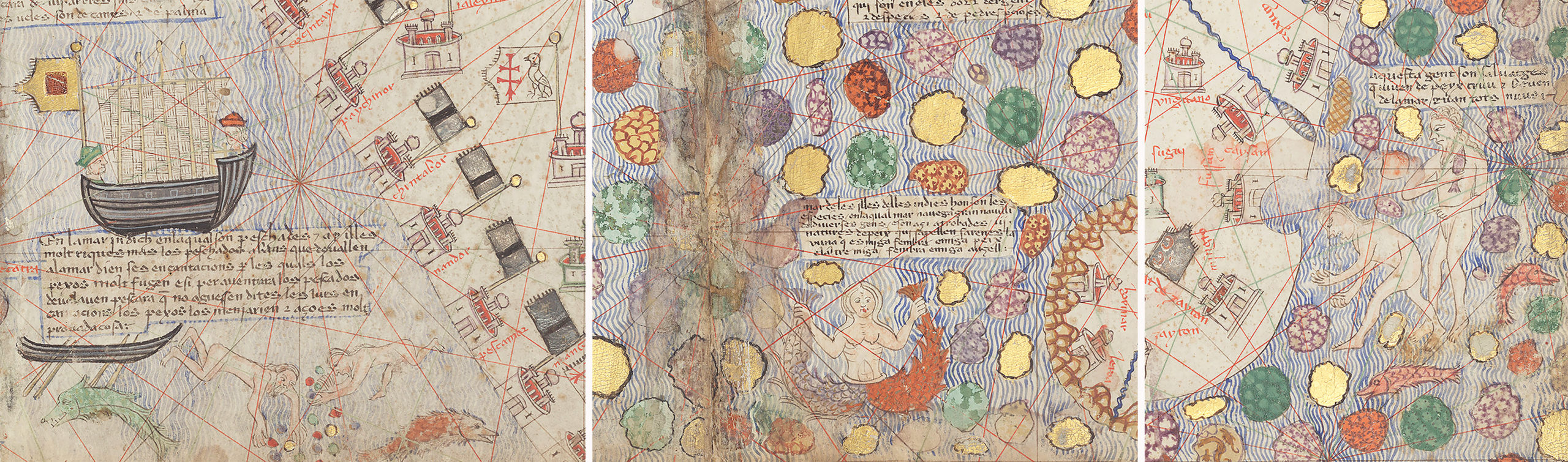

From left: pearl fishers (Sheet 5B), siren (Sheet 6B), and icthyophagi (raw fish eaters) (Sheet 6B), Catalan Atlas, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1375, Majorca (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

Mythical space

Where most medieval mappaemundi incorporated fantastical elements, including mythical beasts or the so-called “monstrous races” (legendary peoples), such as Cynocephali (men with dog’s heads) and Sciapods (one-legged creatures), Cresques attempted to provide as realistic as possible a rendering of both geography and political realms. Most challenging in this respect was his depiction of East Asia. Despite the presence of Europeans in several cities in China, such as Yangzhou, and even after Marco Polo’s famous expedition, East Asia still remained largely unknown to Europeans in the fourteenth century. Here, Cresques could not use portolan charts to accurately plot the region, as European sailors had not yet navigated the area. Cresques relied heavily upon Marco Polo’s travel narrative to fill in the details, including figures that would have appeared almost life-like to medieval viewers, such as sirens in the Indian Ocean, as well as pearl fishers in the Persian Gulf, who Marco Polo noted chant incantations to protect themselves from dangerous fish.

Gog and Magog, Catalan Atlas, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1375, Majorca (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

Cresques also incorporated two mythical figures who appear frequently on the easternmost edges of medieval mappaemundi, the nations of Gog and Magog that figured prominently in the Christian vision of the apocalypse (the destruction of the world and the end of time). According to one of these traditions, Alexander the Great enclosed Gog and Magog, fierce and threatening man-eaters, behind mountains to await the arrival of the Antichrist, at which time they would leave their enclosure and bring death and destruction just before Christ’s Second Coming. By the twelfth century, these vicious peoples were often identified in Christian texts with Jews. Cresques’s depiction is in part faithful to this narrative.

Left: Alexander the Great facing Satan; right: the nations of Gog and Magog with their ruler on horseback, Catalan Atlas, Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, 1375, Majorca (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

We see Alexander the Great facing Satan and pointing to an enclosure in which he will confine the nations of Gog and Magog, represented within a mountainous enclosure. However, rather than appearing as wild nations, they appear as a well-organized army led by a dignified ruler on horseback beneath a large blue canopy. Moreover, the mountains that surround them are distinguished from all other mountains on the map by their use of a wavy border on both sides, rather than only on one side. This pattern more closely resembles the representation of the map’s rivers. The curving lines of the mountain ranges may have subtly represented the legendary River Sambatyon, behind which, according to Jewish narratives, live the ten lost tribes of Israel who dwell under divine protection, isolated from any outside influence, until the arrival of the Jewish messiah. Cresques was likely familiar with several fourteenth-century Jewish texts, that associated the lost tribes with a hope for a messianic future in which Jews were not subordinated by Christianity. By conflating Christian and Jewish mythical imagery, the map communicates different messages depending upon who viewed it. For the map’s patron, it plotted a well-known apocalyptic motif of Gog and Magog onto the map of the world, while at the same time, for Cresques, living in a period of increased persecution under Christian rulers, it highlighted a messianic hope for the lost tribes to cross the River Sambatyon and herald the coming of a Jewish messiah and an independent Jewish future.

In the centuries that followed Cresques’s completion of The Catalan Atlas, religious persecution of the Jewish community of Majorca gravely increased. Within four years of his death in 1391, Majorcan Jews suffered under anti-Jewish riots, at which point, Cresques’s entire family converted to Christianity under severe duress. The more favorable renderings of the Islamic world and a Jewish messianic future in the Catalan Atlas, may suggest that he hoped for a better future for himself and his family in the face of Christian persecution.