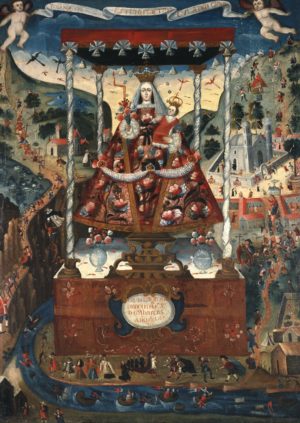

Juan Pedro López, Our Lady of Guidance, c. 1765–70, oil on canvas, Caracas, Venezuela, 41.325 x 26.5 inches, with original frame by Domingo Gutiérrez (Collection of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation); speakers: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Kathryn Santner

Juan Pedro López, Our Lady of Guidance, c. 1765–70, oil on canvas, Caracas, Venezuela, 41.325 x 26.5 inches, with original frame by Domingo Gutiérrez (Collection of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation)

Our Lady of Cocharcas, 1765, oil on canvas, 198.8 x 143.5 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Essay by Kathryn Santner

One of the most striking elements of an eighteenth-century painting of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child from Venezuela is to see these biblical figures dressed in contemporary fashions. The Virgin wears an elaborate dress ornamented with flowers and flourishes, and Christ is dressed like a dandy in a red silk suit rich with gilt embroidery. This painting of Our Lady of Guidance depicts a religious statue as it stood on the main altar (or retablo) of the Church of San Mauricio in Caracas. Paintings of statues such as this were popular across colonial Latin America, and even sometimes feature the vases of flowers or candles that decorated the altar.

Here, the artist, Juan Pedro López, has given us several clues that we are looking at a statue, placing the Virgin on a platform and setting her within the niche of the altar. Her rigid form and frontal gaze also indicate that this is a representation of a statue rather than a person. The fashions of the Virgin and Christ Child reflect the tastes of the era of the painting’s creation (the 1770s) and the rise of a Rococo style in Venezuela.

Miraculous origins of the statue of Our Lady of Guidance

According to pious tradition, in 1688, while sailing from Veracruz, Mexico to Maracaibo, Venezuela, captain Juan Delgado and his crew sighted some enemy ships on the horizon. The sailors prayed to St. Rita, patroness of lost causes, to guide them to safety. Though they successfully evaded the enemy ships, they became lost in a fog. While trying to orient themselves, they discovered a box floating in the sea with a statue of Our Lady of Guidance inside it. Delgado and his men prayed that the statue would bring them safe harbor, which it did. After their arrival in the port of La Guaira, the statue was given to the bishop of Caracas and eventually placed on the altar at the Church of San Mauricio in Caracas, where it became the patroness of a Black confraternity founded in 1701.

A devoted community

The church of San Mauricio, where the sculpture found its home and one of the oldest in Caracas, had three active Afrodescendant confraternities (in addition to the group devoted to Our Lady of Guidance, there were also groups devoted to Saint John the Baptist and the Holy Sacrament). During the colonial period, the members of all three confraternities, both free and enslaved, were part of a West African ethnic group known as the Tari, who were brought to Venezuela as part of the transatlantic slave trade that began in the sixteenth century. Enslaved Africans and their descendants were forced to mine gold, fish and dive for pearls, and work on cacao plantations.

The membership dues and alms raised by the members of the confraternity of Our Lady of Guidance (cofrades) were used for adorning the Virgin of Guidance with the fine vestments seen in the painting here. An inventory of the church made in the decade the painting was created shows the remarkable wealth invested by the community in this votive image. From crowns studded with real and imitation gems, including emeralds mined in Colombia and pearls fished in Venezuela’s coastal waters, to numerous silk dresses, the Virgin was the object of profound veneration and care. These votive offerings were given by individuals or by the confraternity and were common throughout Latin America. They could be extraordinarily lavish, like the emerald-studded crown given to the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception in Popayán, or humble, depending on the social status of the donor.

Juan Pedro López, Our Lady of Guidance (detail), c. 1765–70, oil on canvas, Caracas, Venezuela, 41.325 x 26.5 inches, with original frame by Domingo Gutiérrez (Collection of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation)

Our Lady of Guidance and the Rococo in Venezuela

After the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14), the crown of Spain fell into the hands of the House of Bourbon, a French royal dynasty. With this new leadership came an influx of French customs to Spain and its overseas territories, including a change in artistic taste. The Baroque styles favored under the Habsburgs gave way to Rococo flourishes, classicism, and the influence of the Enlightenment. Though the Bourbons imported French artists to the court in Madrid, Spanish Rococo styles diverged from those of France.

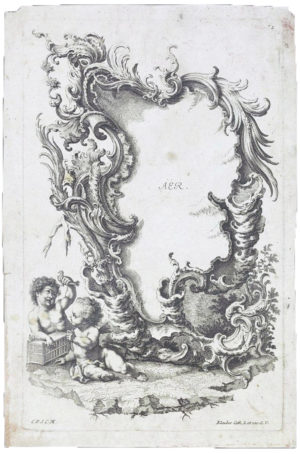

Johann Baptist Klauber and Joseph Sebastian Klauber, One of two plates from a suite of four cartouches with the elements, 1745–65, engraving, Germany (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Venezuela, part of the Viceroyalty of Nueva Granada until 1777, had been under Spanish control since the early sixteenth century. By the eighteenth century, much of the local economy depended on the cultivation and trade of cacao beans, and the illicit trade of cacao on Dutch and British ships put Venezuela in greater contact with European goods, ideas, and artistic styles. While the majority of this trade was for foodstuffs and cloth, this cosmopolitanism led to brushes with European fashions and stylistic modes. The trade links to Europe that supported the colony—as well as a steady stream of migrants from the Canary Islands—also kept it in closer contact with European artistic trends than more isolated artistic centers like Cuzco.

Bernardo Rodríguez, Saint Jerome, 18th century, oil on sheet, Quito, Ecuador (Ivan Cruz Collection)

Visible in López’s painting of the Virgin are the several hallmarks of the international Rococo style, most notably its pastel palette and lack of straight lines. López decorates the altar niche with serpentine curves and counter-curves that echo the dress of the Virgin and the gilt frame carved by his frequent collaborator, Domingo Gutiérrez. The frame Gutiérrez created for Our Lady of Guidance is an exuberant confection of foliate and floral ornamentation rendered in gold leaf that winds around the painting in sinuous waves.

The scallop shell painted at the top of the niche also recalls the forms in the frame, whose delicate striations evoke the natural forms of shells, flower petals, or vegetation. In fact, the term “Rococo” comes from the combination of the words rocaille (from the French for rockwork or pebbles; rocalla in Spanish) and coquille (shell). Rocaille is a term that refers to the undulating forms imitating shells, rocks, leaves, and scrolls, used in Rococo architecture and ornamentation in the eighteenth century. Rocalla was brought to Latin America via European engravings, such as those by the Klauber brothers of Augsburg, and was particularly popular in the painting of colonial Quito.

The artists, Juan Pedro López and Domingo Gutiérrez

Juan Pedro López, Our Lady of Guidance, c. 1762, oil on panel, 100.3 × 69.2 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The population of Caracas remained remarkably small compared to other viceregal cities like Lima and Mexico City. Because of its location, Venezuela had many immigrants from the Canary Islands, known as isleños, who made up a quarter of its 7,000 residents. The Canary Islands, which lie off the coast of Morocco, were conquered by the Crown of Castile in the fifteenth century and became an important stopover point on transatlantic crossings. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a steady stream of isleño migrants arrived in Caracas as well as other Caribbean colonies of Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and Cuba in hopes of escaping famine and overpopulation. Among those migrants were accomplished artists and craftsmen like Domingo Gutiérrez.

Juan Pedro López, who would become one of Venezuela’s most accomplished artists of the eighteenth century, was also isleño, the son of migrants from Tenerife. During his career, he created over two hundred artworks, most of them painting on canvas or panel. He also created sculpture and ornamental decoration, refreshed and repaired artworks, gilded frames and retablos (altarpieces), and appraised estates for wealthy caraqueños (people from Caracas). While he did produce a few portraits during his lifetime, almost all of López’s paintings are of religious themes. Among them are numerous statue paintings, showing other religious statues in their niches.

Indeed this is not the only painting López produced of Our Lady of Guidance; an almost identical version, thought to have been produced for a convent of Discalced Carmelite nuns, is now at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. In this version, the niche behind the Virgin is not clearly depicted but only suggested by the stand beneath her.

Left: Juan Pedro López and Domingo Gutiérrez, Tabernaculo de los evangelistas, oil on cedar, 134.3 x 110.5 cm (Collection of the Asociación Venezolana Amigos del Arte Colonial, Caracas); right: Juan Pedro López and Domingo Gutiérrez, Armchair for the Solium of the Caracas Cathedral, 1766, gilded and painted Spanish cedar, fabric upholstery, 116.04 cm high (Denver Art Museum)

Our Lady of Guidance is the product of López’s frequent collaborations with Domingo Gutiérrez, a cabinetmaker (ebanista) and sculptor who also designed frames. The Canary Islands had close ties to mainland Europe and that influence can be seen in Gutiérrez’s sculpted altars (retablos) and frames for paintings including Our Lady of Guidance.

Together with Gutierrez, López helped introduce the Rococo to Venezuela several decades after it had taken root in France and Germany. López’s palette of pink-reds, ochres, gray-whites, and blues borrow from the pastel hues favored by eighteenth-century French artists like Jean-Marc Nattier and Jean-Honoré Fragonard. [2] Other artists in Latin America were influenced by this artistic movement, including New Spain’s Miguel Cabrera, who may in turn have influenced the work of Juan Pedro López through works imported from Mexico City to Caracas. While Rococo originated as a secular style in French interior design, in the workshops of Latin America, it found use primarily in religious art. The spread of Rococo was a global phenomenon, and examples of its influence can be found from the Philippines to Brazil.

A splendorous work

The splendor of this work—its size (48 x 33 inches) and extravagant Rococo frame—suggest that it may have been commissioned not for a private home but for a religious institution of some prominence. As noted earlier, López’s other version of Our Lady of Guidance in Boston was thought to have been painted for a convent of Clarissan nuns in Caracas. However, little is known of this piece’s origins or its history prior to the twentieth century, when it entered the collection of Alfredo Machado Hernández, founder of Caracas’s colonial art museum, the Quinta de Anauco.