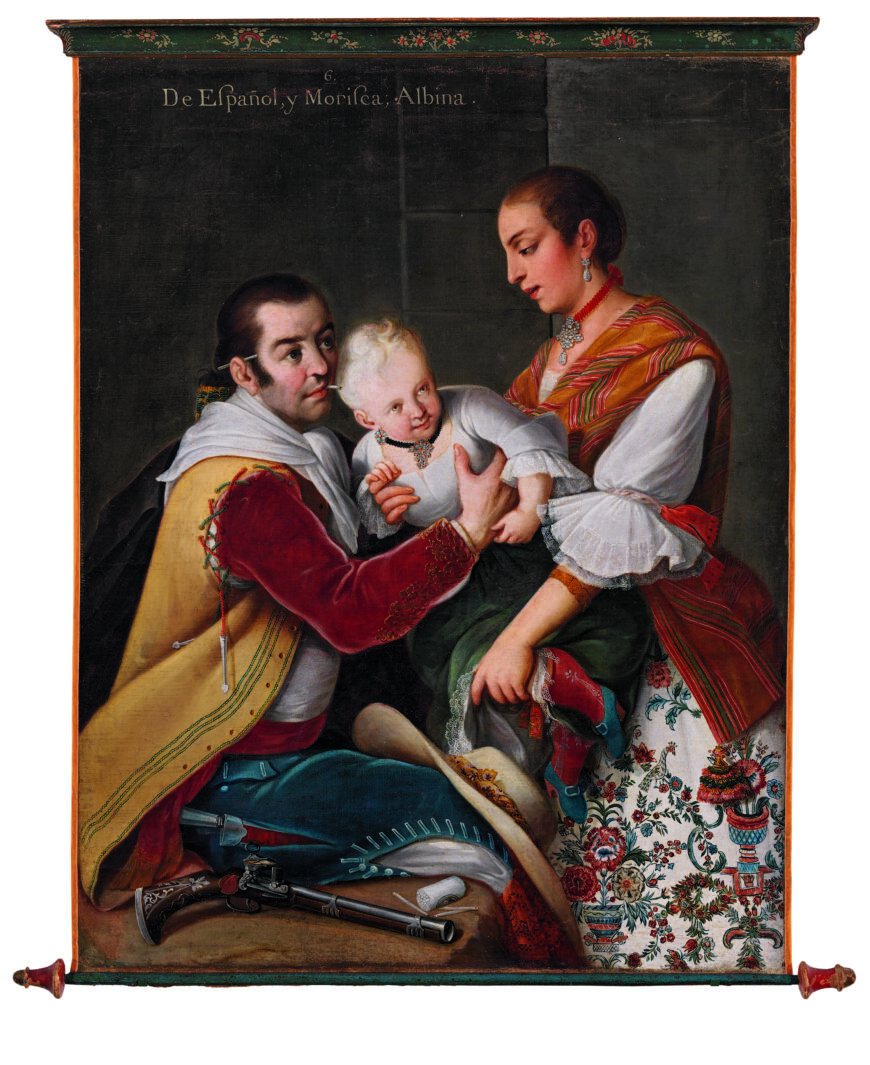

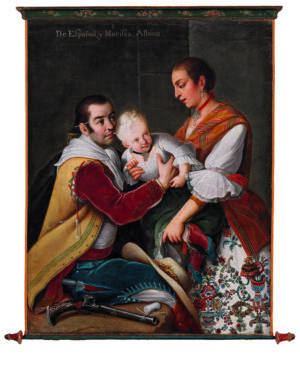

Miguel Cabrera, 6. From Spaniard and Morisca, Albino Girl (6. De español y morisca, albina), 1763, oil on canvas, 131.1 x 105.1 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

One of the eternal questions of an art historian is how does art reflect life? Does art reinforce, perpetuate, or even invent the ideals it represents? In other words—how can we make sense of the messaging embedded in a given work made in a specific place, at a specific time, and thereby inflected with something of the “essence” of its makers and environs?

Miguel Cabrera, set of casta paintings (14 shown of 16 total), 1763, oil on canvas (various collections)

Casta paintings, made in 18th-century Mexico, are some of the most fascinating objects for pondering of such questions. Created in sets of sixteen, each one depicts a married couple of different races and their offspring, labeled with the terminologies used to describe their racial classification. The labels help us to untangle a web of ideologies, yet when we compare the paintings across sets (as in one set of 16 vs another set of 16), what we find is a lack of standardization. The same racial mixture could be given an entirely different name in one set to another. Furthermore, the visual properties, and therefore the messaging, also differ greatly in each painting and across sets. This type of comparative framework is used in many disciplines. By looking at something similar yet different, we gain a more nuanced understanding of that which we seek to interpret.

Left: Miguel Cabrera, 6. From Spaniard and Morisca, Albino Girl (6. De español y morisca, albina), 1763, oil on canvas, 131.1 x 105.1 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art); right: Miguel Cabrera, 7. From Spaniard and Albino, Return-Backwards (7. De español y albino, torna atrás), 1763, oil on canvas, 132 x 101 cm (private collection, Mexico)

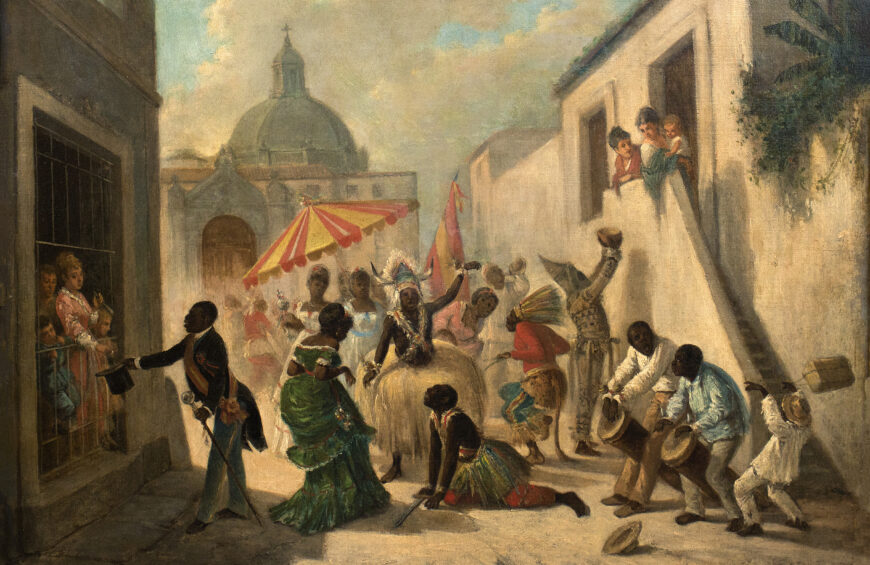

Let us take as an example a painting by one of the most famed artists in colonial Mexico, Miguel Cabrera. This essay will focus on the sixth painting in his sixteen painting casta set produced in 1763 entitled From Spaniard and Morisca, Albino Girl. In the painting on the left the morisca mother’s skin is painted just a shade darker than her Spanish husband, but curiously their daughter, called an albina, is exaggeratedly white with blonde hair. This painting is an especially notable example within the set for the ways that it crystallizes the bizarre and at times fantastical constructions of race within the Spanish colonial world. In addition to its subject matter, the painting stands out for its original condition. It, unlike the fifteen others in the set, is still attached to its original wooden dowels that were used to roll up the painting for ease of transport. Through an examination of Cabrera’s From Spaniard and Morisca we gain a more nuanced understanding of the link between the manipulation of racialized ideas and their connection to the physical manifestation of an object.

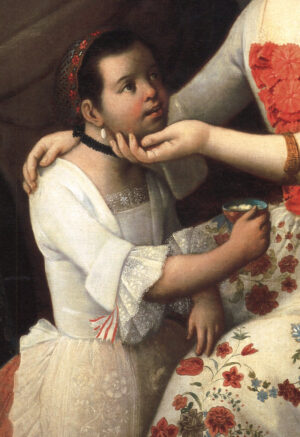

“Torna atrás” child (detail), Miguel Cabrera, 7. From Spaniard and Albino, Return-Backwards, 1763, oil on canvas, 132 x 101 cm (private collection, Mexico)

Albino people and the sistema de castas

Casta paintings produce a racial taxonomy that developed as part of the Age of Enlightenment, when intellectuals on both sides of the Atlantic began to question tradition and develop secular, scientific methodologies for understanding the natural world. These ideas, as they relate to human races, were best crystallized in German scientist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach’s 1776 On the Natural Varieties of Mankind which proposed five categories of mankind. Soon these pseudoscientific methods of categorization were expanded to make sense of an increasingly racially heterogeneous society, seen most vividly in the sistema de castas developed in the Spanish colonial world. Perhaps one of the most bizarre and fantastical of these categories was the development of the albino/a type. Today we know that albinism is an inherited condition causing the body to produce little to no melanin, and occurs in people from every continent. In the 18th century, however, albinism was seen as monstrous and a subject of debate for the ways that albino people differed so radically from their forebearers. [1] One theory argued that albino people were only descended from dark-skinned peoples, specifically Africans. As pale as the albina child is in the Cabrera painting, in the next in the series, number 7, she (or another woman like her) produces a child with skin darker than both hers and her Spanish husband.

This child, labeled torna atrás, or return-backwards, reveals her mother’s “hidden” African ancestry. This reveals the racist pseudoscientific ideologies inherent in the sistema de castas: Africans, no matter how intermixed with Spaniards, could never become “Spanish.” This differed from the racial category labeled Indio which refers to people of Indigenous ancestry. Within a few generations of intermarriage, the resultant offspring, carrying one eighth Indigenous heritage, were seen to become español, or Spanish. If purity could be eventually achieved by one group but not the other, the system is clearly not the result of rational inquiry, but rather one built on prejudice and constructed hierarchies. Unfortunately, the Cabrera painting depicting the castiza’s Spanish child is currently missing, so we turn to another set in order to learn the fate of the Indigenous bloodline.

José de Páez, From Spaniard and Castiza, Spaniard, c.1770–80, oil on copper (private collection)

In From Spaniard and Castiza, Spaniard, painting seven of twelve in a casta set by José de Páez, the castiza is one fourth Indigenous, the rest Spanish. Once she marries a Spaniard, their child becomes Spanish. This is made evident in the painting through their Spanish style of dress and the rosy cheeks of the children who are a shade lighter than their mother. Keep in mind that the albina—who is depicted as far lighter in complexion than the castiza, yet both with majority (3/4) Spanish ancestry—instead produces a child far darker who is labeled a throwback. While both Indigenous and African peoples were subject to xenophobia, bias, and exploitation within the Spanish colonial world, it is evident, via the construction of racialized hierarchies in the casta paintings, that there was an especially strong prejudice against Africans and their descendants.

While the casta paintings create the impression of an orderly society with transparency regarding the race and therefore the social position of its mixed race inhabitants, the reality was far more complex. The casta terminologies for the mixed races were not legal labels, and essentially amounted to colloquialisms. On the ground people used various methods to manipulate their identities based on phenotype, class, and social connections. In this sense, the casta paintings project Spanish anxiety around controlling an increasingly heterogeneous and racially transient society. [2]

The object and its maker

Miguel Cabrera was the preeminent New Spanish painter active in Mexico City in the first half of the 18th century. His oeuvre includes projects as far ranging as church altarpieces, viceregal portraits, and miniature works on copper. He was the official painter of the Archbishop of Mexico Manuel José Rubio y Salinas, and was also a favorite painter of the Jesuit order.

Miguel Cabrera, 6. From Spaniard and Morisca, Albino Girl (6. De español y morisca, albina), 1763, oil on canvas, 131.1 x 105.1 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Cabrera famously spearheaded the study of the icon of the famous Virgin of Guadalupe in Tepayac, Mexico. Entitled American Marvel, the commentary affirmed the miraculous nature of the image, concluding that its unique blend of oil, tempera, and gouache paints had to have been miraculously created without human hands (this is referred to as an acheiropoieton). [3] Cabrera was tasked with creating official copies of the icon, and served as arbiter of authenticity for copies and elaborations produced by other artists. While during his lifetime Cabrera was most famous for his monumental religious paintings, today he is best remembered for his only casta series, a leading example of the genre.

Let us return to the painting. As in the entirety of the sixteen painting series, the figures in From Spaniard and Morisca, Albino Girl are pushed forward in the picture plane, their bodies overlapping and intimately arranged (compare them, in contrast to the relatively distant arrangement of Páez’s casta family). With this “zoomed in” view, the artist is able to lavish the figures with a plethora of detail. The Spanish father wears a leather military uniform laced and tied at the shoulder in such a way that suggests the thickness and heft of its material. The morisca mother wears a floral chintz skirt, a white blouse, and an elaborate rebozo shawl that includes metallic threads. Their albina child wears a colorful outfit including a white shirt, green skirt, red tights, and blue shoes.

As the parents pass the child between them, the center of the composition brings together their colorful and varied clothing. Leather, wool, lace, velvet, and metal all come together to form a visual cornucopia of splendor. [4] In addition to their clothing, the objects in the painting including the father’s cigarettes as well as his gun, are rendered with rich detail. Cabrera’s talents are on full display. His intended audience—Spaniards—relished in intimate views of life in Mexico, a land that for Europeans was still far off and unknown.

Pistol and clothing (detail), Miguel Cabrera, 6. From Spaniard and Morisca, Albino Girl, 1763, oil on canvas, 131.1 x 105.1 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

The painting’s Mexican subject matter, intended for export, is also visible in its very construction. As mentioned above, it is still connected to its original dowels that were used to roll up and easily transport the canvas. The fifteen others have been altered over the centuries and framed, so when the albina girl was discovered in 2015, its original condition was of keen interest to scholars. These paintings were expressly intended for export to Spain, and even the canvases were prepped for optimal durability when rolled up like scrolls for transport.

Far from portraits of distinct individuals, the casta paintings project local “types,” viewed through the eyes of the elite, whether Spanish or creole. Miguel Cabrera’s set stands as a paramount of the genre for its intimacy and painterly detail. And within the set, From Spaniard and Morisca, Albino Girl stands out for its state of preservation, keen attention to color and detail, and perhaps even the especially compelling story of the albina, who embodies the complexities (and absurdities) of the sistema de castas.