A rare and elaborate child portrait from Venezuela by an Afro-descendant artist.

Diego Antonio de Landaeta, Portrait of Petronila Méndez, 1763, oil on panel, Caracas, Venezuela, 6.5 x 7 5/8 inches (Collection of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation). Speakers: Dr. Kathryn Santner and Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank

Diego Antonio de Landaeta, Portrait of Petronila Méndez, 1763 (Caracas, Venezuela), oil on panel, 6.5 x 7 5/8 inches (Collection of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation)

A young girl in a pink and white gown gazes out at the viewer. Her elegant dress and upright posture belie the fact that she is not even ten years old. This painting is remarkable not only because it is the only known portrait of a child from colonial Venezuela, but also because it is the only known work by the Afrodescendant painter Diego Antonio de Landaeta.

Unidentified artist, Portrait of Doña Teresa Mijares de Solórzano y Tovar, after 1732, oil on canvas, 194 x 111.5 cm (Galeria de Arte Nacional, Caracas)

An uncommon portrait

Though the Spanish colony in Venezuela was established in the early 1500s, the first known portrait dates to about a hundred years later and depicts Don Francisco Mijares de Solórzano y Díaz de Rojas, “provincial” and mayor of Caracas. As with elsewhere in the Spanish Americas, the main body of portraits depicted male aristocrats, ecclesiastics, and government officials. In the 18th century, the society portrait emerged, showing the elites of various Latin American cities in elaborate dress. It was also at this time that portraits of women began to appear, some created as pendants to their husbands’ portraits. However, few society portraits from Venezuela survive, as many were destroyed in the 19th century during the war for Independence when they were mistaken for royal portraits. Among the extant colonial portraits of women is that of Doña Teresa Mijares de Solórzano y Tovar, First Countess of San Javier. These portraits were generally not created by artists who specialized in portraiture; since it was not until the 19th century, with the work of Juan Lovera, that Venezuela gained its first dedicated portraitist.

While the portrait of Méndez is the only known portrait of a child from Venezuela, portraiture of children emerged in the 18th century in other parts of Latin America, particularly in New Spain. Children were often depicted individually, to celebrate an accomplishment such as entrance into the church or university, or as part of larger family groups.

Petronila Méndez (detail), Diego Antonio de Landaeta, Portrait of Petronila Méndez, 1763 (Caracas, Venezuela), oil on panel, 6.5 x 7 5/8 inches (Collection of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation)

The portrait of Petronila Méndez features many of the traditional attributes found in both European and Latin American portraiture: she is pictured in three-quarter view, looking directly at the viewer. Her posture is rigid and she leans back slightly, as did New Spanish women of the 18th century in their own portraits. As in other Latin American portraits, Méndez is identified not by her distinctive facial characteristics but by the attributes with which she is depicted.

Nicolás Enríquez, Maria de Padilla y Cervantes, c. 1735, oil on canvas, 89.9 x 66 cm (Brooklyn Museum, New York)

Typical for portraits of children, Méndez sports the dress and jewelry of a much older woman. She wears a pink bodice, perhaps made from imported Asian silk, with a white skirt embellished with flowers over a chemise trimmed with lace from Flanders. On her wrists she wears matching pearl bracelets along with a necklace, earrings, and hairpin, all adorned with pearls fished from Venezuela’s coastal waters. Her costume and abundant jewelry, made of both local and imported luxury items, indicate some degree of wealth, but do not display the opulence of colonial elites in their portraits (such as the Countess of San Javier above). She holds a nosegay delicately between the forefingers of her right hand and a closed fan in her left. Flowers could be symbols of transience or virginity in portraiture and closed fans symbolized modesty, as does the hand held to her torso. On her cheek can be seen a chiqueador—a false beauty mark—a common feature in 18th-century Mexican portraiture. Though chiqueadores were typically seen as a symbol of sexual availability and flirtation, they were frequently included in portraits of young children in the 18th century, who were dressed and presented in adult fashions.

In contrast to most portraits from the 18th century, Méndez is not placed in an architectural setting—typically shown standing in front of a red velvet curtain and next to a table covered with symbolic objects. Rather she is shown against a backdrop of clouds. In this way, this small image resembles portrait miniatures, which typically favored backdrops of clouds or gradients.

The Landaeta School

While only recently gaining recognition in scholarship, there were significant numbers of Afrodescendant painters and artisans in Latin America during the colonial period, though their activity is best documented in Brazil and Cuba. Many of Venezuela’s most prominent artists were free pardos, including Francisco José de Lerma y Villegas, José Lorenzo Zurita, Rafael Ochoa, and the Landaeta family, of which Diego Antonio de Landaeta was part.

Antonio Jose de Landaeta, Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, c. 1795, oil on canvas, 75.6 x 47.6 cm (Denver Art Museum)

The painter Diego Antonio de Landaeta was born to Faustina Rosa de Landaeta, an enslaved morena, and was probably the son of Sergeant Major Don Manuel de Landaeta, her enslaver. As the portrait of Petronila Méndez is the only known work by Landaeta’s hand, his life and artistic output are traceable only through the documentary record. By the 1760s, Landaeta had achieved the rank of Maestro de Pintor (master painter). We know that Landaeta produced at least one other portrait, that of the aristocrat Don José Domingo Jerez de Aristeguieta in 1784, and like many other painters of his day, also worked as an appraiser for the estates of wealthy caraqueños. Landaeta was active in the confraternity of Our Lady of Sorrows at the Church of Altagracia in Caracas, and donated several artworks to the parish church of Petare, where he lived. While this is the only work definitively attributed to Landaeta, it has been suggested that he is responsible for a somewhat naive painting of the Immaculate Conception created in Cúa, in the Valles del Tuy, near Landaeta’s residence in Petare. However, given the refined treatment of the face of Petronila Mendez in her portrait, Landaeta’s authorship of the Inmaculada seems unlikely. Landaeta’s status as a pardo libre did not, however, prevent him from owning and selling enslaved people, which he did at several points during his life.

Only five paintings by the Landaeta family bear their signatures. Many more works are attributed to la Escuela de los Landaeta, or the Landaeta school. Along with the artists Juan Pedro López and Francisco José de Lerma y Villegas, the Landaetas were some of the most significant painters active in 18th-century Caracas. Common characteristics among the works—heavens rendered in pink-ochre, crowns adorned with pearls, the distinctive haloes made up of beams of light of differing intensities, and the depiction of the stars around the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception—have led scholars to group these paintings under the heading Landaeta school. [1] With only one work by Diego Antonio de Landaeta known, it is hard to say whether he can be grouped stylistically with the Landaeta school. It is likely, however, that he received training from other members of the family/school.

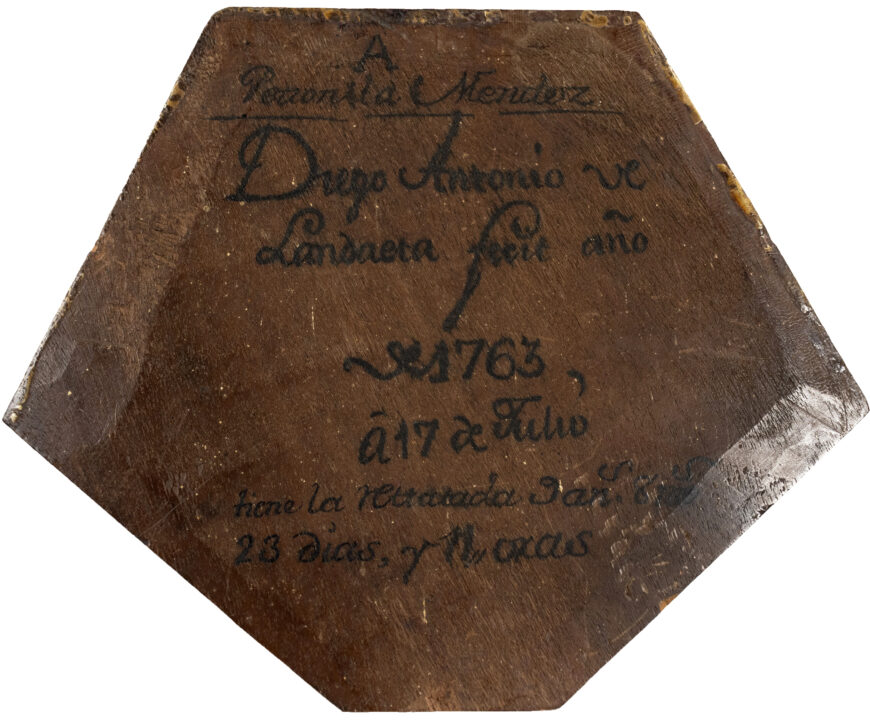

Inscription on reverse, Diego Antonio de Landaeta, Portrait of Petronila Méndez, 1763 (Caracas, Venezuela), oil on panel, 6.5 x 7 5/8 inches (Collection of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation)

A curious inscription

Perhaps the most unusual feature of this portrait is the inscription found on the reverse of the wood panel. It reads:

A Petronila Mendez Diego Antonio de Landaeta fecit ano de 1763 a 17 de Julio tiene la retratada 9 ans, 8 mes, 23 dias y 11 oras.

To Petronila Méndez Diego Antonio Landaeta made this on July 17, 1763 when the sitter was 9 years, 8 months, 23 days, and 11 hours old.

Using this information, we can calculate that Méndez was born around October 24, 1753.

The inscription also identifies Landaeta as the author of the work. Notably, the inscription begins with “A Petronila Mendez” (to Petronila Méndez), suggesting that Landaeta presented the work to her or that the work was created for her. The presence of signatures in colonial Latin American painting varies. It was a fairly common practice in New Spain but quite unusual in Venezuela, where painters were not regarded as anything more than craftsmen. It was only in the late 18th century when artists began to sign their work with regularity. Landaeta’s signature, and his use of the Latin term “fecit” (made), were a self-conscious proclamation of his status as an artist.

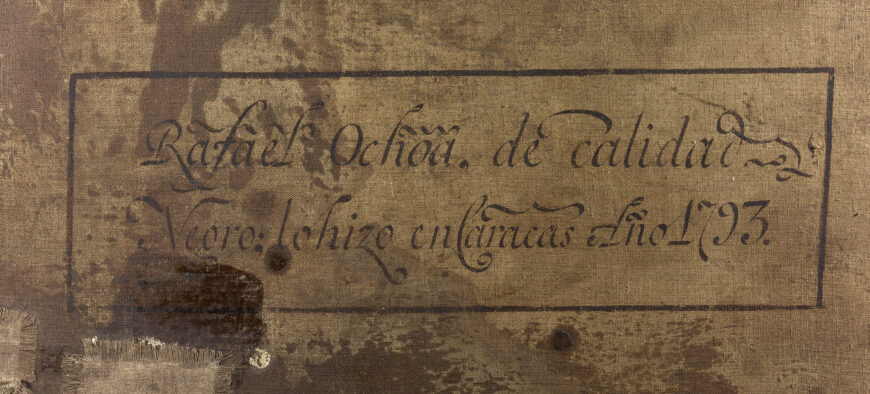

Inscription on reverse (detail), Rafael Ochoa, Portrait of Don José Bernardo de Asteguieta y Díaz de Sarralde, 1793, oil on canvas, 115.6 x 96.5 cm (Denver Art Museum)

It also bears comparison to another portrait signed by Rafael Ochoa of Don José Bernardo de Asteguieta y Díaz de Sarralde. Ochoa, who was Afrodescendant like Landaeta, notably included his racial category, “de calidad negro,” in the inscription. Ochoa and Landaeta’s signatures appeared at a point—the second half of the 18th century—in which signed works by José Campeche and Miguel Cabrera were being imported into Venezuela. Seeing other painters carry out this practice may have influenced the Black artists of Venezuela.

Petronila Méndez (detail), Diego Antonio de Landaeta, Portrait of Petronila Méndez, 1763 (Caracas, Venezuela), oil on panel, 6.5 x 7 5/8 inches (Collection of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation)

The why of the portrait

Petronila was the eldest of seven children born to María Josefa Romero and Pablo Méndez. Her parents were both Spanish creoles (and cousins through their grandmothers, who were sisters). While her family had some wealth and owned several properties, in part due to her father’s business acumen, they were not aristocratic or part of the planter elite of Caracas. The family’s middling status makes the existence—and survival—of this portrait somewhat unusual. Portraiture was traditionally the preserve of elites. It was only in the 18th century, with the arrival of the Bourbon monarch Philip V, that portraiture became accessible to the wealthy merchant class. Why then was this painting created?

Unlike many aristocratic portraits, the inscription on Méndez’s panel does not make any claims for the family’s noble status or ancestry. The Méndez family did not have a large ancestral home to fill with portraits of descendants. Still, the attention to the finery of the costume and its careful repetition of formulas found in other society portraits suggests that it may have been commissioned by the family as a sign of their social arrival.

Though it might be tempting to suggest that the portrait was made to attract a potential match for Méndez, her age at the time of its creation makes that suggestion unlikely. Marriages among Caracas’ elite were more typically brokered when women were in their early 20s and men in their late 20s. In this instance, Petronila would not be married for another ten years, in 1773 when she was 19. Her marriage to the son of immigrants from Bayonne, France suggests the Méndez family had some status, as foreigners often married into wealthy creole families to establish themselves in a new society.

As no contract between the Méndez family and Landaeta exists, we cannot be sure if the portrait was created in isolation or if the family commissioned portraits of their other children. It seems most likely that this work was created as a sign of the Méndez family’s increasing wealth, and was probably not the only portrait commissioned by the family.

Conclusion

This portrait is a remarkable document, both of a non-elite child living in 18th-century Caracas, and of the artist who created it. Images of non-elite classes in colonial Latin America are few, and portraits of children even rarer. So too are signed works by Black artists, though they dominated artistic production at the time. This small portrait has filled in an important missing piece of Venezuelan art history, and given its recent rediscovery, we can be hopeful that more objects will come to light, further enriching our understanding of the period.

Notes:

[1] Alfredo Boulton, Historia de la pintura en Venezuela, volume 1, 2nd edition (Caracas: Armitano, 1972), p. 223.

Additional resources

This work at the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation

The Thoma Foundation’s Art of the Spanish Americas collection

Painters of African descent in the Colonial Spanish America

Alfredo Boulton, Historia de la pintura en Venezuela, volume 1, 2nd edition (Caracas: Armitano, 1972).

Carlos F. Duarte, Diccionario biográfico documental. Pintores, escultores y doradores en Venezuela. Período hispánico y comienzos del período republicano (Caracas: Fundación Galería de Arte Nacional, Fundación Polar, 2000), pp. 115–19.

Robert J. Ferry, The Colonial Elite of Early Caracas: Formation and Crisis, 1567–1767 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989).

James Middleton, “Reading Dress in New Spanish Portraiture: Clothing the Mexican Elite, circa 1695–1805,” New England/New Spain: Portraiture in the Colonial Americas, 1492–1850, edited by Donna Pierce (Denver: Denver Art Museum, 2014), pp. 101–46.

Jaime Moreno Villarreal, “In Praise of Heat and Fan,” El retrato novohispano en el siglo XVIII (Puebla: Museo Poblano de Arte Virreinal, 1999), pp. 145–52.

Gonzalo Obregón, “The Child and Colonial Painting,” Artes de México, number 129 (1970), pp. 22–34.

Janeth Rodríguez Nobrega, “El rey en la hoguera: la destrucción de los retratos de la monarquía en Venezuela” Imagen del Poder: VI Encuentro Internacional Sobre Barocco (La Paz: Editorial Visión Cultural, 2012), pp. 90–95.