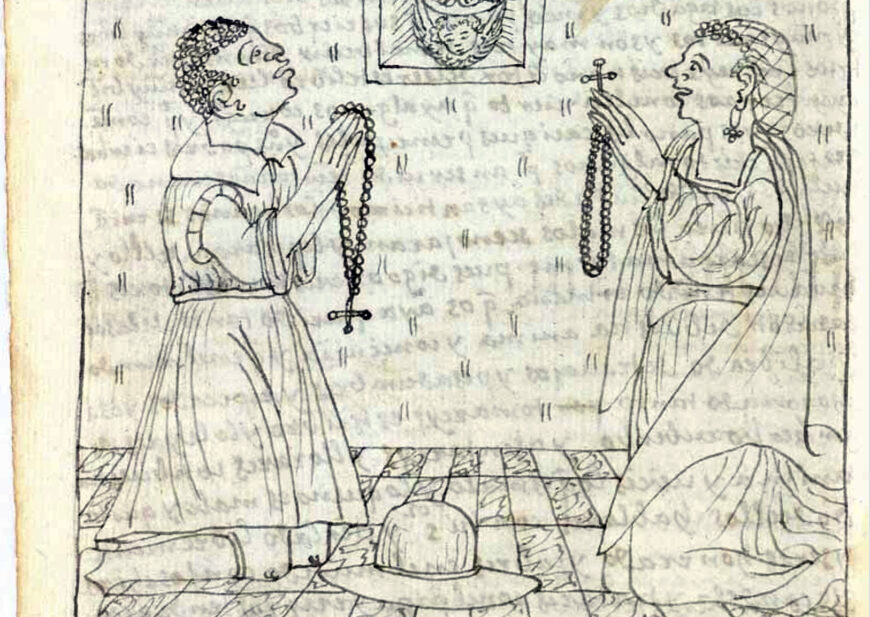

“Black men and women who come from bozales from Guinea” (detail), from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, El primer nueva corónica i buen gobierno (1615), p. 717 (Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

A man and woman kneel in the supplicant position, their hands grasped in prayer holding rosaries, while they look upwards at an image of the Virgin Mary. The pair, rendered in ink on paper in line drawings, are referred to in the accompanying text as “bozales from Guinea,” terms which point to their origins on the continent of Africa.

“Black men and women who come from bozales from Guinea,” from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, El primer nueva corónica i buen gobierno (1615), p. 717 (Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

Including Africans

This image is from a nearly 1200-page manuscript written in 1615 by Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, entitled El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno (The First New Chronicle and Good Government). In over one thousand hand-written pages and almost four hundred line drawings, Guaman Poma relates Andean history, beginning with Inka mythology, history, and the state of early colonial Peru. The author’s primary goal was to highlight the abuses of the Spaniards against the Indigenous Andeans and to advocate for their better treatment and increased representation in the colonial bureaucracy. Guaman Poma’s argument takes on moralizing tones, positioning the Spaniards as wayward Christians for their abusive behavior, and highlighting the contrasting piety of Indigenous peoples, particularly those from noble families.

While most of the manuscript focuses on Indigenous Andeans (both historically and in relation to Spaniards in the colonial period), a small portion of the text looks as well to the presence of Africans within the Viceroyalty of Peru. Guaman Poma’s inclusion of Africans points to the reality of the Spanish colonial world which profited from the transatlantic slave trade and resulted in some of the earliest interaction between Europeans, Africans, and Indigenous Americans.

What, then, does the Andean nobleman tell us about Africans in Peru? The way that Guaman Poma features Africans and Afro-descendants in the manuscript gives us a view of the interactions between two groups who were not in power—decentering the viewpoints of Spanish colonizers. Spaniards called Africans directly from the continent bozales, which comes from a Spanish word for muzzle. They viewed bozales as potentially rebellious, violent, and lacking in Spanish acculturation. Guaman Poma, in contrast, describes bozales as true Christians:

Blacks, humble, Christian, and well married, like the bozal blacks from Guinea, they have taken on the faith of Jesus Christ and understand Christianity, are faithful, believe in God, keep the holy commandments and [practice] the holy and good works of mercy, are obedient servants of their masters…The Spaniards say that the bozal blacks are not worth anything, but they do not know of what they speak…Guaman Poma in Nueva Corónica

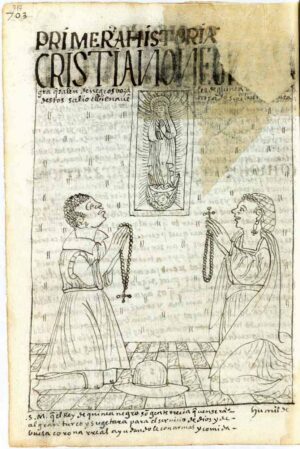

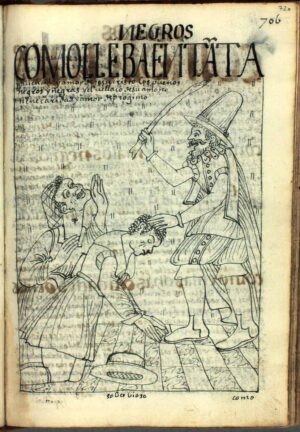

“Africans endure the abuses of their Master with the patience and love of Christ,” from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, El primer nueva corónica i buen gobierno (1615): p. 720 (Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

Later in the manuscript, Guaman Poma shows the same bozales cruelly beaten by their abusive master despite their devout faith. The image is violent and disturbing, and there are many others like it in the manuscript showing Indigenous Andeans beaten and killed by corrupt Spanish authorities. Despite the surface-level parallels of such images of suffering Africans and Andeans, Guaman Poma is first and foremost concerned with the advancement of his own people, and particularly of noble Andeans like himself.

Negros criollos: thieves and drunks

In contrast with the pious bozales, Guaman Poma negatively characterizes another African group that he refers to as negros criollos, or creole Black people. These are Afro descendants, in this case people born in Peru of African heritage.

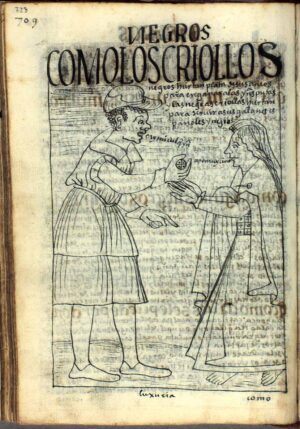

“How the black creoles steal money from their owners and give it to Indian prostitutes,” from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno (1615): p. 723 (Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

In “How the black creoles steal money from their owner and give it to Indian prostitutes” Guaman Poma depicts a Black man exchanging money with an Indigenous woman. He describes Black creole men as “bachelors, rebellious, liars, thieves, pickpockets, robbers, tricksters, drunks, tobacco users, cheaters, low lives, pure scoundrels who often murder their own masters.” So what, in Guaman Poma’s mind, has changed from one generation to the next?

Spaniards thought of the negros criollos in more positive light, who, while still enslaved, had become more Hispanized than those born in Africa. Guaman Poma, however, inverts this hierarchy claiming that the influence of the Spaniards in fact catalyzes the nefarious behavior of those Africans who were more like their Spanish overlords. Furthermore, he is concerned about potential miscegenation with the Indigenous woman, who he depicts wearing authentic Andean dress similar to that worn before the conquest. Ultimately Guaman Poma, while depicting Africans in a different light than would be seen in a European viewpoint, advocated for the separation of the Indigenous and African populations, which aligned with the agenda of Spanish colonial administrators who feared alliance-building and uprisings.

Guaman Poma’s Africans in the Nueva Corónica represent just a small portion of the enormous manuscript. Still, they provide us with a revealing glimpse at interactions between Africans and Natives which rarely received attention in either the visual or written records of the period. Within these images we can see an Indigenous artist and author constructing ideas about race and hierarchy in an era in which Spaniards, as the colonial power, were the controllers of such processes. By celebrating the bozales and denigrating the negros criollos, Guaman Poma condemns the Spaniards in his mission to advocate for his own people.