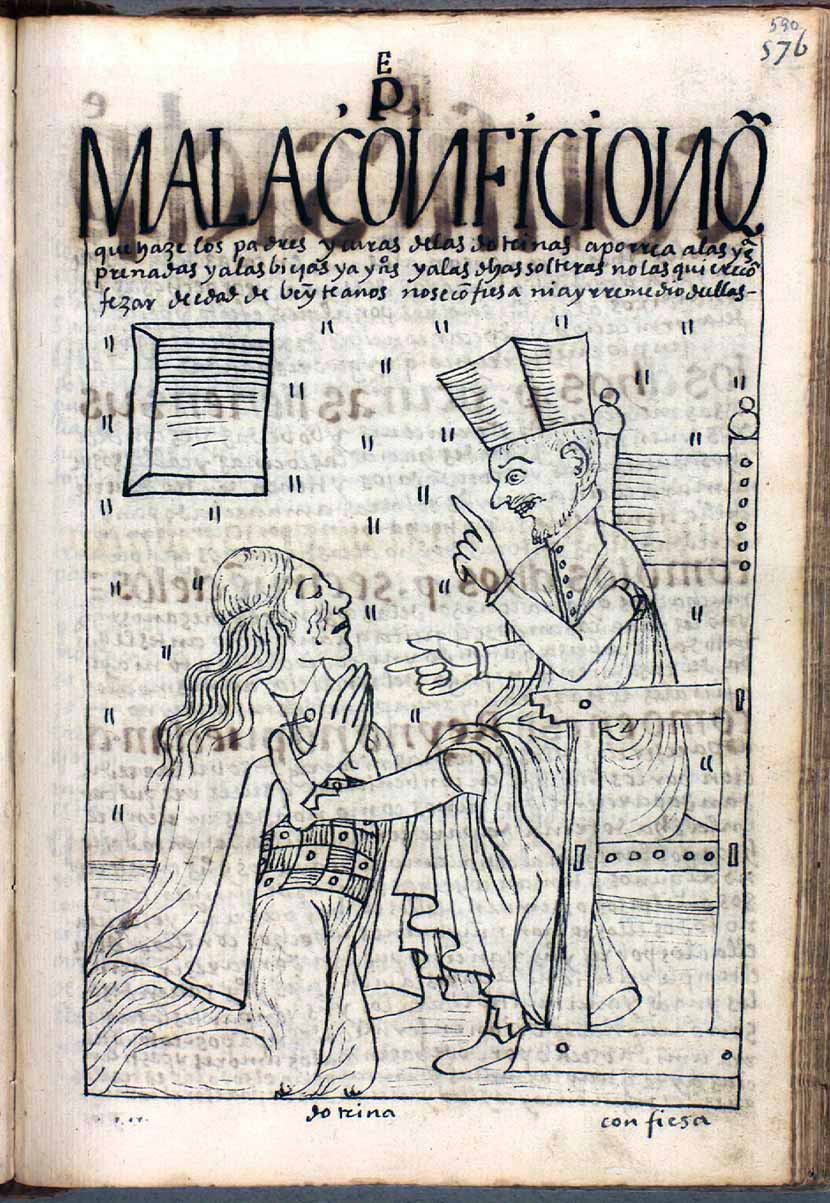

Bad confession. Page 590 from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, c. 1615 (image from The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

“The Bad Confession”

Bad confession. Page 590 from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, c. 1615 (image from The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

An Andean woman kneels with her hands clasped in prayer. Her Indigenous identity is conveyed by her style of dress; she wears a lliclla (shawl) fastened with a tupu (garment pin) that opens to reveal tocapu-like designs on her dress underneath. She looks up at the priest, with tears in her eyes, as he rams his left foot in her abdomen. The violent image becomes all the more poignant on closer inspection of her swollen belly, indicating the woman’s pregnancy, which is described in the accompanying text.

This image, entitled “The Bad Confession,” is in Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala’s illustrated manuscript, known the The First New Chronicle and Good Government (El primer nueva coronica i buen gobierno), dated to around 1615. The first half of Guaman Poma’s illustrated manuscript provides a comprehensive description of Inka imperial history as well as an encyclopedic account of life under Inka rule, covering topics as diverse as the ritual calendar, agricultural practice, religious beliefs, different ways of burying the dead, and the various professions of the empire’s inhabitants. The second half of the manuscript details the abuses committed by the Spaniards during the early period of colonial rule in the Viceroyalty of Peru. Guaman Poma’s vivid imagery provides some of the only surviving visual sources that reveal the often violent treatment that Indigenous people endured under their Spanish rulers.

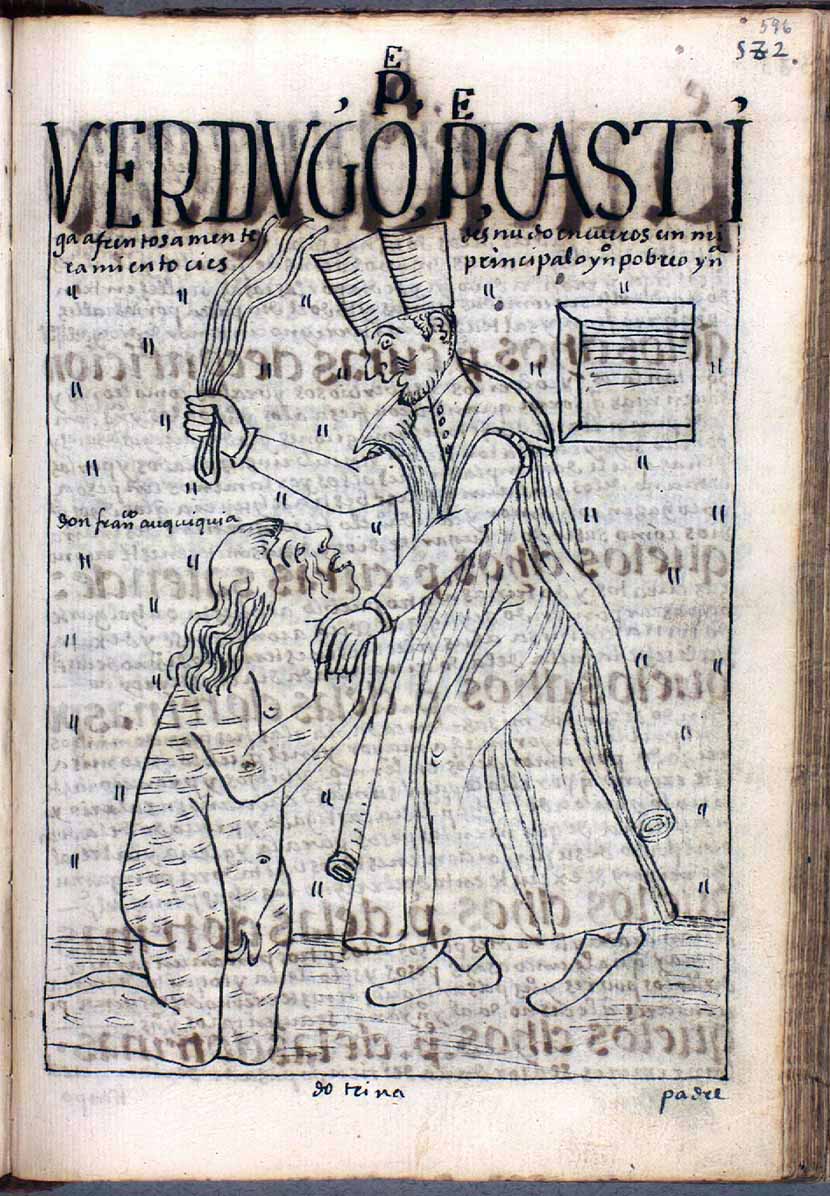

Executioner: the cruel parish priest metes out punishment indiscriminately. Page 596 from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, c. 1615 (image from The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

“The Bad Confession” image participates in a larger visual and textual argument about the ability for native Andeans to rule themselves without Spanish intervention. Indeed, Guaman Poma presents the colonial period as a “Pachacuti,” a Quechua term that he uses to refer to a world turned upside down. As part of his plea to King Philip III, Guaman Poma strategically argues that Christianity existed in the Andes long before the Spanish invasion and that it is the Spaniards who are the exemplars of “bad Christians.” The visual mechanics of “The Bad Confession” support this thesis.

Hanan and hurin

The drawings in The First New Chronicle and Good Government often correspond to the Andean spatial hierarchies of hanan and hurin. Hanan is associated with dominance, masculinity, and superiority while hurin holds the connotations of weakness and femininity. [1] Within an Inka context, hanan and hurin were not conceived as occupying dichotomies of superior and inferior but were instead considered complementary relationships bound through systems of reciprocity. In this new colonial context, however, Guaman Poma has strategically deployed these concepts to highlight the depravity of the Spaniards.

Bad confession. Page 590 from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, c. 1615 (image from The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

In “The Bad Confession,” the woman occupies the hanan part of the composition (the internal right) while the priest is situated in the hurin segment (the internal left), thus displaying the moral superiority of the Andean woman, who is inflicted with physical violence in her most vulnerable region. In this “world upside down,” the priest, the supposed embodiment of morality, succumbs to a morally reprehensible act.

Illustrated manuscripts in early colonial Peru

There only exist three known illustrated manuscripts produced in early colonial Peru: two versions of Mercedarian friar Martín de Murúa’s account, separately titled History of the Origin and Royal Genealogy of the Inka Kings of Peru (Historia del origen y genealogía real de los reyes ingas del Perú, c. 1590–1615) and History of Peru (Historia del Pirú, 1616). The latter, which contains thirty-eight stunning watercolor illustrations depicting the lives of the Inka nobility, has recently undergone extensive conservation at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. The third and most well-known of the three is Guaman Poma’s New Chronicle (1615). The dearth of Peruvian manuscripts stands in stark contrast to the 1,000+ illustrated manuscripts that survive from colonial Mexico. The likely reason for this is because there did not exist a manuscript tradition in the pre-Columbian Andes as there did in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica. The notion of drawing images and writing on paper had no precedent in the Andes until the arrival of the Europeans.

Inka ruler, in Martín de Murúa’s Historia general del Piru, completed in 1616, Pen and ink and colored washes on paper bound between pasteboard covered with morocco leather Leaf: 28.9 × 20 cm (11 3/8 × 7 7/8 in.), Ms. Ludwig XIII 16 (83.MP.159) (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Nevertheless, these three manuscripts offer a compendium of Andean life both before and after the conquest of the Inkas. The wealth of information they provide has been of critical importance to archaeologists, historians, art historians, and anthropologists as a means to understand Inka history as well as the lived experience of Indigenous peoples in the early years of Spanish colonial rule.

Notes:

[1] See Mercedes López-Baralt, “From Looking to Seeing: The Image as Text and the Author as Artist,” in Guaman Poma de Ayala: The Colonial Art of an Andean Author, ed. Rolena Adorno et al. (New York: Americas Society, 1992), pp. 14–31.

Additional Resources

A facsimile of the Historia general del Piru (also called The Getty Murúa)

Essays on The Getty Murúa from the Getty Museum

Scientific Investigation of Martín de Murúa’s Illustrated Manuscripts (Getty)

Rolena Adorno, Guaman Poma: Writing and Resistance in Colonial Peru (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000)

Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government, trans. Roland Hamilton (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009)

Guaman Poma de Ayala: The Colonial Art of an Andean Author (NYC: Americas Society, 1992)

Lisa Trever, “Idols, Mountains, and Metaphysics in Guaman Poma’s Pictures of Huacas,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 59/60 (2011): 39–59.