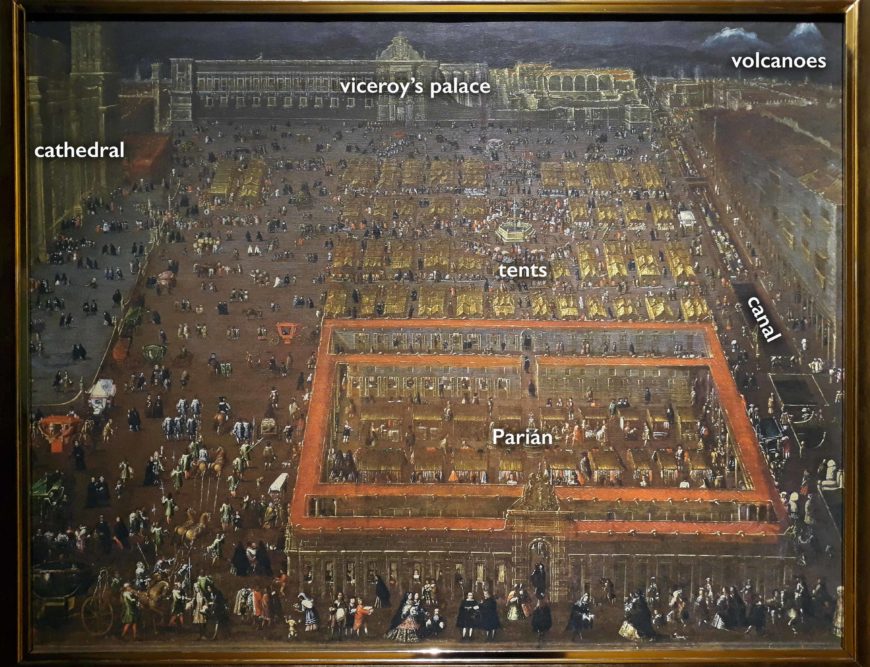

Cristóbal de Villalpando, View of the Plaza Mayor of Mexico City, c. 1695, oil on canvas (Corsham Court Collection, Wiltshire)

In Mexico City’s main plaza, a bustling scene unfolds before our eyes. Horse-drawn carriages carry the city’s elite. Most people are on foot, and some can be seen promenading in a line at the canvas’s bottom edge. Other people congregate before the city’s massive cathedral on the left. Temporary tents are pitched in the furthest portion of the plaza, with people selling their goods. A more permanent structure made of stone surrounds even more shops in the foreground. Looking at the hundreds of individuals depicted here, we see a kaleidoscope of dress and accoutrements. We also see an artist attempting to represent the diverse ethnic makeup of the Spanish viceroyalty of New Spain.

Cristóbal de Villalpando, View of the Plaza Mayor (Zócalo) of Mexico City, c. 1695, oil on canvas (Corsham Court Collection, Wiltshire)

This painting, by the famous artist Cristóbal de Villalpando from about 1695, is well-known for its subject. It shows the large market (called the Parián) in the Plaza Mayor (or Zócalo) of Mexico City, which existed until the 19th century when it was demolished (you won’t see it in the Zócalo today). Its name was borrowed from its counterpart in Manila (in the Philippines, which was also controlled by Spain at this time). Merchants brought goods from across oceans to sell to the residents of the city in the Parián. Mexico City, and the broader territory of New Spain, were at the center of a large network of global trade.

Goods, people, and ideas travelled from Manila (having themselves come from many parts of Asia) to the port city of Acapulco via galleons (sailing ships often called Manila Galleons). From Acapulco, these goods either made their way to Mexico City or were carried to Veracruz on the Gulf Coast, at which point they’d be shipped across the Atlantic to Europe. Goods flowed likewise from Europe to New Spain. What makes this center even more complex and fascinating is that it did not just receive goods from Europe and Asia, but likewise sent finished goods and natural resources across the Atlantic and Pacific, and even down the coasts to the viceroyalty of Peru. Silver was among the most popular materials to travel to Asia from the Americas. The constant flow of objects, ideas, raw materials, and people added to the dynamic character of New Spain, and especially in a city like Mexico City which had a worldwide reputation as a beautiful, wealthy city energized by the constant influx of things.

Cristóbal de Villalpando, detail of the Parián, View of the Plaza Mayor of Mexico City, c. 1695, oil on canvas (Corsham Court Collection, Wiltshire)

Transpacific trade and cosmopolitanism

Lacquerwares, folding screens, ivories, spices, silks, Chinese porcelain—these are but some of the many objects and natural resources that traveled across the Pacific from Asia to New Spain. Goods were often labeled as “de China” or “from China—a reference to something coming from what we call Asia today, and not paying close attention to where things originated specifically in Asia. In Villalpando’s painting, in the stone Parián enclosure it seems that some merchants are selling cloth, possibly silk, indicated by the multicolored lengths of fabric hanging from individual stalls.

Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City, New Spain, late 17th century (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Talavera vessel with the image of a crane, adapted from Chinese porcelain, 17th century, earthenware (Franz Mayer Museum, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Artists in New Spain began to adapt the forms and visual modes they encountered in these foreign goods, developing new art forms or modifying older ones. Japanese folding screens were popular trade items that stimulated Novohispanic artists to adapt the Japanese byobu (folding screens) into biombos. Many paintings, prints, sculptures, and furniture also incorporate representations of things that made their way to New Spain via trade networks.

José Manuel de la Cerda, Writing cabinet on table, c. 1750, Wood, Mexican lacquer, gilding, and silver drawer pulls, 102 x 155 cm (The Hispanic Society)

For example, we find Chinese blue-and-white porcelains represented on altars with sculptures of Christ, or locally produced ceramics adapting Chinese motifs, such as with talavera poblana (local ceramic production in Puebla). Clearly, the flow of goods through places like the Parian, that Villalpando so dynamically captures in paint, affected many different aspects of Novohispanic culture.

The transpacific trade also resulted in Asian peoples coming to new Spain, where they or their descendants worked in cities like Acapulco, but also Puebla and Mexico City. While some were enslaved, others worked in many different trades and occupations—adding yet again to the diverse society of the Spanish viceroyalty that Villalpando represents here.

Cristóbal de Villalpando, detail of the lower edge of the View of the Plaza Mayor of Mexico City, c. 1695, oil on canvas (Corsham Court Collection, Wiltshire)

A history painting?

Adding to the lively scene are details like dogs running or playing, children, people engaged in conversation, and people on the canal (that no longer remains today). This is an idealized view of daily life in Mexico City, where all peoples seem to exist in relative harmony.

Cristóbal de Villalpando, detail of the viceroy’s palace and volcanoes, View of the Plaza Mayor of Mexico City, c. 1695, oil on canvas (Corsham Court Collection, Wiltshire)

Villalpando crafts a painting that gives the impression of a snapshot, or a realistic portrayal of Mexico City’s main plaza. Nevertheless, he took certain liberties. The Parian was under construction when he painted the scene, and here it looks more majestic than it likely did (and even more symmetrical than it actually was). One account describes it as “horrible,” in reference to its unsightliness. [1] The entrance to the viceroy’s palace is also larger than it was, perhaps a way to elevate the dignity of the viceroy himself.

The painting shows identifiable structures, many of which still stand today. Villalpando took great care to detail fabrics and faces, animals and spaces, almost creating a visual argument that this really is what the Zocalo looked like. The painting also references a recent important event in New Spain’s history: the burning and partial destruction of the viceroy’s palace after uprisings in 1692 over food shortages. The large horizontal palace in the back of the painting shows the partially destroyed structure. Villalpando also includes clear topographic features in his painting to situate the scene in Mexico City. In the far background we see the snow capped volcanoes of Popocatepetl and Iztaccihuatl—still famous today for their appearance above the skyline of Mexico City. Even the angle that Villalpando chose to depict the city is considered correct; he possibly observed the Zocalo from the top of one of the houses from the western side of the plaza.

Cristóbal de Villalpando, detail of the Parián, View of the Plaza Mayor of Mexico City, c. 1695, oil on canvas (Corsham Court Collection, Wiltshire)

Shopping

Francisco Clapera, two paintings from a set of sixteen casta paintings, c. 1775, 51.1 x 39.6 cm (Denver Art Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The painting’s focus on shopping and material consumerism reinforces the wealth of many criollo (Spaniards born in the Americas) and peninsulare (Spaniards from the Iberian Peninsula) residents of Mexico City and New Spain more broadly who had amassed fortunes from silver mining and other means. Villalpando’s portrayal of the residents of Mexico City as active consumers extends beyond the upper levels of society, but this is an idealized vision of the Zócalo and the city’s inhabitants. In reality, anxieties over ethnic mixing and blurred social divisions existed, as the later genre of casta paintings so explicitly communicate. Sumptuary laws tried to restrict not only what people could wear in public, but who could wear them. In Villalpando’s painting, people of many different social stations wear luxurious clothes and jewelry.

The cosmopolitan nature of Mexico City, with its steady influx of luxury goods from afar, meant that there was a desire to own and wear fanciful things. But there was also the fear that those of lower social status could give an impression of being above their station by wearing nice things. Travelers passing through Mexico City comment on how even servants were seen in pearls—to them an oddity and a social transgression.

Cristóbal de Villalpando, View of the Plaza Mayor of Mexico City, c. 1695, oil on canvas (Corsham Court Collection, Wiltshire)

An ideal projection

For all of its attention to detail, Villalpando’s painting should not be read as an accurate image of what life was actually like in its lived experience for everyone in the capital of New Spain. The painting celebrates the city, the viceroyalty, its wealth, and its cosmopolitanism—but it is an ideal projection. It was commissioned by the viceroy Gaspar de Silva, Count of Gelves, who had been responsible for the food shortages in the 1690s. He apparently paid for the painting, and returned to Spain with it. The vision that Villalpando projects undoubtedly appealed to the viceroy who wished to believe that he had brought prosperity to the Spanish colony.

Notes:

[1] Richard Kagan, Urban Images of the Hispanic World, 1493–1793 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), p. 161

Additional resources

Barbara Mundy and Dana Leibsohn, “Patterns of the Everyday,” on Vistas: Visual Culture in the Spanish Americas, 1521–1820

Cristóbal de Villalpando (Mexico City: Fomento Cultural Banamex, 1997)

Donna Pierce et al., ed., Asia & Spanish America: trans-Pacific artistic and cultural exchange, 1500–1850: papers from the 2006 Mayer Center Symposium at the Denver Art Museum (Denver: Denver Art Museum 2009)

Donna Pierce et al., ed., At the crossroads the arts of Spanish America & early global trade, 1492–1850: papers from the 2010 Mayer Center symposium at the Denver Art Museum (Denver: Denver Art Museum 20012)