José Campeche y Jordán, Portrait of Governor Ramón de Castro, 1800, oil on canvas, 165.1 x 228.6 cm (Museo de San Juan, San Juan; photo: Tamara Díaz Calcaño)

Standing proudly and dressed in a bright, brocaded military uniform, Ramón de Castro—the governor of Puerto Rico—holds his cane and hat in his right hand while he extends his left toward the view behind him. He gestures to the soldiers and resources at his command, and to the land he defended during his time as governor. The well-regarded Puerto Rican artist José Campeche was commissioned by the city of San Juan to commemorate Castro’s successful defense of the city from British troops in 1797.

The expanse of land beyond San Cristóbal is Puerta de Tierra, where tents and blocks of soldiers in formation stand. At the distance, under Castro’s arm is the San Gerónimo fortress. Toward the right, connecting the isle of San Juan to the big island of Puerto Rico, is the San Antonio bridge. José Campeche y Jordán, Portrait of Governor Ramón de Castro (detail), 1800, oil on canvas, 165.1 x 228.6 cm (Museo de San Juan, San Juan; photo: Tamara Díaz Calcaño)

The siege

The defense of San Juan, the capital city of Puerto Rico, took place in 1797, during the Anglo-Spanish War. This conflict started when France and Spain allied against Great Britain, resulting in battles in the Atlantic and the Caribbean.

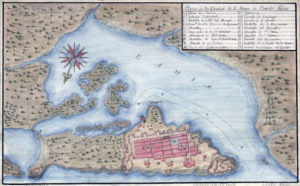

Map of San Juan, Puerto Rico, showing the walled outline of San Juan and the whole isle, c. 1770, pen-and-ink and watercolors (Library of Congress)

In 1797, a large fleet of British ships took the Caribbean island Trinidad, a Spanish colony since 1592. After this victory, the British turned their attention to the Spanish colony of Puerto Rico, which was of particular interest for its strategic position and its potential for sugar production. After arriving in the waters near San Juan, the British gave Governor Castro the chance to surrender without violence. Castro and his men remained steadfast in their intention to defend the territory.

Under Castro’s command, local (Spanish) and French soldiers defended the city from its fortified walls and beyond as the English attacked both by sea and land. Volunteer soldiers came from San Juan and adjacent towns, even the artist Campeche took up arms. The Spanish administration had invested heavily in fortifying San Juan throughout the 18th century, creating a walled system around the capital with smaller forts around it, like that of San Gerónimo. While the British soldiers attacked from land, from San Mateo de Cangrejos and what is today known as Condado, they were not able to cross onto the isle of San Juan. The defense forces, like the Puerto Rican Fixed Regiment, camped and kept the enemy at bay from Puerta de Tierra. Volunteer soldiers came from San Juan and adjacent towns, even Campeche took up arms. The British admitted defeat after an unfaltering defense.

An image of military accomplishment

Detail of plinth with the governor’s titles. José Campeche y Jordán, Portrait of Governor Ramón de Castro, 1800, oil on canvas, 165.1 x 228.6 cm (Museo de San Juan, San Juan; photo: Tamara Díaz Calcaño)

Campeche’s portrait of Castro commemorates this victory, featuring the governor standing in an exterior space beside the San Cristóbal fortress, built on the northeastern corner of the city. The fortress was part of the fortification project started in the second half of the 17th century and was designed primarily to protect San Juan from eastern land attacks. Castro is also surrounded by military attributes and emblems, including cannons. Beside him, on the lower right, a plinth is inscribed with the governor’s lineage, titles, and military career, as well as references to the defense of the Puerto Rican capital in 1797. The plinth is crowned by his monogram and an assortment of military symbols, with the shield of the Marquees of Lorca (the title held by the Castro’s father) over the inscription.

Behind Castro is a pedestal and column, common elements in 18th-century European portraits. The steep walls of the fortress dominate the right side of the composition. Castro’s left arm guides the eye over the cannon in the middle ground, to one of the parapets of the fortress and an ample landscape, featuring the area of Puerta de Tierra (the land immediately east to the walled city of San Juan) and Puerto Rico beyond the bay.

Campeche reduced the land of Puerta de Tierra considerably to better include references to the defense against the British. Just outside the walls of San Cristóbal soldiers stand in formation along military tents. Beyond is the small fort of San Gerónimo, which can be spied just under Castro’s arm. Toward the right of his head, the San Antonio bridge extends over water to connect the isle of San Juan to the big island of Puerto Rico.

Left: Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, General José de Urrutia, c. 1798, oil on canvas, 199.5 x 134.5 cm (Prado); right: Juan Rodríguez Juárez, Portrait of the Viceroy, the Duke of Linares, c. 1717, oil on canvas, 81.88 x 50.39 inches (MUNAL)

The artist’s process

José Campeche, The Daughters of Governor Ramón de Castro, 1797, oil on canvas, 31.75 x 45.38 inches (Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico)

Since the 1770s, Campeche had been painting devotional images and portraits for San Juan society. In fact, Castro’s portrait was not the first work Campeche had painted for the governor—he had been commissioned to paint a portrait of Castro’s daughters in 1797.

To create his portrait of Castro, Campeche adapted elements from his own previous works, as well as portrait conventions from the broader Spanish-controlled world. Portraits of prominent figures in Puerto Rico including archbishops, viceroys, and governors followed Spanish models. Artists could look to portraits sent from Spain including the official portraits of the king that were sent to overseas territories. Francisco Goya’s portrait of General José Urrutia is one possible model for Castro’s portrait—we know it was distributed widely in the form of a print, and it is possible that Campeche borrowed Urrutia’s pose for Castro’s portrait. Also like Castro’s portrait, male elite portraits from New Spain, such as one showing the viceroy, the Duke of Linares, often include lengthy lists of titles and positions, as well as similar compositional conventions. Portraits were important ways to communicate the sitter’s social standing by noting an individual’s lineage, important relationships, titles, work, and education by including coats of arms and inscriptions with this information—such as we see in Campeche’s portrait of Governor Castro.

José Campeche, Miguel Antonio de Ustáriz, 1789–92, oil on canvas, 60 x 41.5 cm (Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña)

Because Campeche, like so many other artists in the Spanish Americas, borrowed and adapted from established portrait conventions, many of his portraits share the same formula. In his portrait of Governor Miguel Antonio de Ustáriz, we see similarities to the portrait of Castro. Ustáriz is represented in what is likely a room in his mansion. He is finely dressed as a colonel of the Spanish Royal Guard Infantry, with a cane in his right hand and a map of San Juan in his left. There is also a plan for a public building, clearly referring to his civil projects. On the left side of the composition, Campeche created a tall opening to include Ustáriz’s most ambitious policy: the paving of the city’s streets. All these details operate the same way the plinth inscription does in Castro’s portrait, as they point to his social position and influence. The sitter’s left arm also guides our eyes to the opening and the view of one of the city’s streets with workers in action, just as Castro’s does to the battle behind him. As is clear, both paintings share a similar composition, yet they are inverted. In both of these portraits of governors, Campeche responds to the interests of his sitters by representing their work and position in Puerto Rican society. He highlights important events or policies carried out through their administrations, and he allots prominent portions of the painted surface to the representation of the military and urban landscapes that were the scene of their actions.

Governor Castro’s portrait allows a consideration of Campeche’s production in the late 18th and early 19th century in a Latin American and Spanish context. This 1800 work reveals that the centuries-long prevalence of certain painting conventions in Spanish American portraiture was alive and well in the Caribbean by this date. It also suggests the same preoccupation with social standing in the peripheries of the empire even amongst those on temporary stays in the region, like governors. It also provides insight into the movement of images through prints and copies which served as both instruction and reference to artists in the region.