Indigenous Andean painters such as Diego Quispe Tito reinvigorated Cuzco’s artistic scene after the death of the Italian Jesuit painter Bernardo Bitti and other Spanish and Italian painters who traveled to the Viceroyalty of Peru in the late sixteenth century to establish their artistic careers. Quispe Tito imbued his compositions with powerful religious imagery that combined Italian, Flemish, and Indigenous pictorial traditions.

The end of time

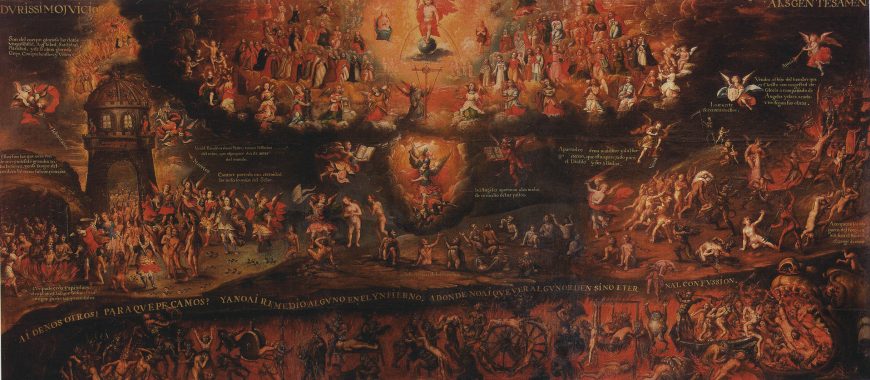

Diego Quispe Tito, detail of Hell, Last Judgment, oil on canvas, 1675 (Convento de San Francisco, Cusco, Peru)

His painting of the Last Judgment from 1675 located in the Convento de San Francisco in Cuzco provides an enduring reminder of the fate of humanity on Judgment Day. Sinners in hell depicted along the lower register of the composition receive an array of bodily tortures — we see individuals stretched across medieval breaking wheels, burning in bubbling cauldrons, and engulfed within the jaws of a Hell mouth. The souls in heaven (at the top), by contrast, surround the ascended Christ in an orderly formation.

Diego Quispe Tito, detail of Heaven, Last Judgment, oil on canvas, 1675 (Convento de San Francisco, Cusco, Peru)

Word and image

Quispe Tito’s canvas retains a strict tripartite scheme of Heaven, Purgatory, and Hell through the use of textual glosses to delimit the painting’s three compositional layers. The texts describe their accompanying scenes in vivid detail, thereby creating a strong interaction between linguistic and visual representation. The glosses add an additional layer of meaning to the image that would have been accessible only to the privileged few that were literate in Spanish. Nevertheless, the visual cues alone provide ample information about Christian eschatology (End of Days) for the purposes of instruction and evangelization.

![Diego Quispe Tito, detail, "there is no longer any remedy in hell, where there is no order to be had but [instead] eternal confusion" Last Judgment, oil on canvas, 1675](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Quispe-Tito-LJ-d3-870x113.jpg)

Detail, Diego Quispe Tito, “There is no longer any remedy in hell, where there is no order to be had but [instead] eternal confusion,” Last Judgment, oil on canvas, 1675 (Convento de San Francisco, Cusco, Peru)

European models through prints

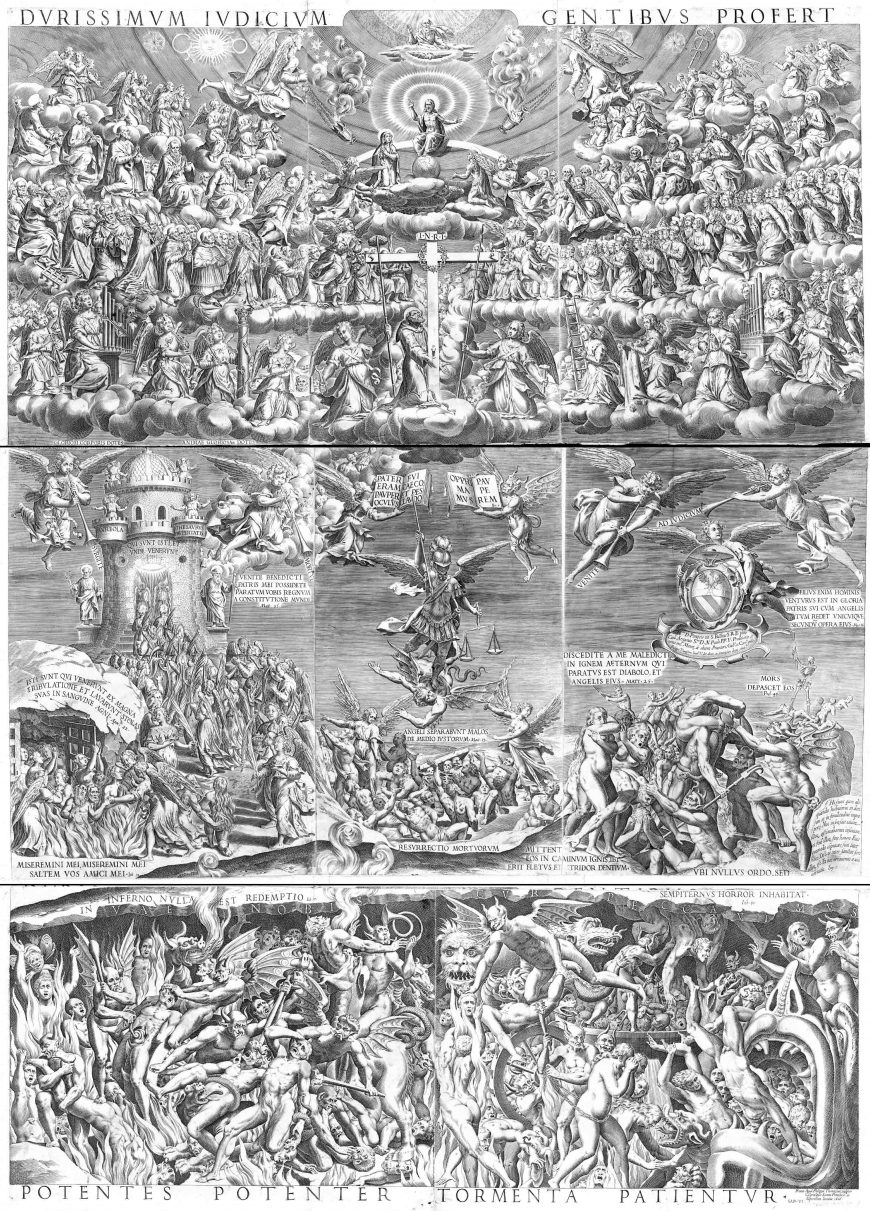

The Last Judgment is modeled from a 1606 engraving by Philippe Thomassin, a French-born engraver who spent the majority of his life in Rome. It remains unclear whether Quispe Tito had access to Thomassin’s original engraving or a seventeenth-century copy by the Flemish engraver Matthaeus Merian. Regardless of the precise source used by Quispe Tito, his Last Judgment reveals the importance of European models in colonial Andean painting, while at the same time demonstrating the creativity of seventeenth-century artists in determining the painting’s color palette and incorporating unique compositional details.

Christian themes related to the End of Days continued to preoccupy Andean patrons and artists throughout nearly the entirety of the colonial period. For example, the mestizo artist Tadeo Escalante produced a mural painting of the Last Judgment in 1802 at the church of Huaro located just outside of Cuzco.

Escalante’s and Quispe Tito’s compositions share the very same print source, despite being produced over a century apart. Escalante’s bright color palette and preference for flattened, simplified forms, however, signals a major turning point in colonial Andean painting that occurred shortly after Diego Quispe Tito completed his painting.

Additional Resources:

Ananda Cohen-Aponte, Heaven, Hell, and Everything in Between: Murals of the Colonial Andes (University of Texas Press, 2016)

Rodríguez Romero, Agustina & Siracusano, Gabriela (2010) “El pintor, el cura, el grabador, el cardenal, el rey, y la muerte. Los rumbos de una imagen del Juicio Final en el siglo XVII.” Eadem Utraque Europa 6 (nos. 10-11): 9-29.

Read more about the arts of the Spanish Americas

Learn more about engraved sources for paintings in colonial Andean art on Project on the Engraved Sources of Spanish Colonial Art