On a vibrantly colored keru cup from colonial Peru, exotically dressed figures, apparently a royal Inka couple, stand surrounded by flowers, vivid designs, and even a rainbow. A keru is a ceremonial Andean beaker that was an important part of Inka culture prior to the arrival of the Spaniards. This vessel was produced in the Viceroyalty of Peru, a Spanish colonial administrative district created in 1542 that included large parts of South America. It might surprise us to find Inka on a colonial vessel—a time after the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors (conquerors). But, although we speak of a Spanish “conquest” of the Andes, which started in the 1530s, Inka society did not disappear after the European invasion. Aspects of social and political bonds, religion, cults, and art—although often reduced or mixed with European characteristics—persisted. Even with the clash of cultures, the Inka (among other peoples) adapted to the new circumstances, as did the European intruders. The Spaniards were challenged to understand an indigenous society where nature was sacred, the sun, moon, stars, mountains, and rivers were venerated as gods and even the ruler, the Sapa Inka, was deified.

The Inka continued to use these types of cups in the early viceregal era, but soon the Spaniards grew suspicious. Why did the Andeans insist on continuing to use them? Were they somehow powerful? Was it possible to hide secret messages in their mysterious iconography that could evoke rebellions against Spanish rule? The Spaniards ultimately decided to destroy kerus in massive campaigns in the later sixteenth century.

A cup not made merely for drinking

Keru (also spelled kero or quero) vessels are typically associated with Inka culture (15th-16th century), but they originated with the Tiwanaku culture (6th – 9th century) in present-day Bolivia. They can also be found in other Andean societies like the Wari (8th – 10th century), Sicán (10th – 11th century—see the image below), Chancay (12th-14th century) or Chimú (14th – 16th century) in the territory of what is today Peru.

Aquillas, Sicán (Lambayeque), 10th – 11th century, gold (The Metropolitan Museum of Art), photo: Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The Andean Quechua term keru primarily specified a “wooden cup.” While wood is the most common material of these vessels, there are also examples made of gold or silver (correctly, although not commonly, called aquillas), stone, or ceramic. Although precious metals like gold and silver did not have the same meaning for Andeans as for Europeans, the material did matter. Associated with the luminous sun, golden kerus were reserved for the Inka ruler. Venerating nature, especially the sun and the moon, the Inka saw their ruler as the descendant of the sun god and his wife as the daughter of the moon. In the same way, the silver cups, reflecting divine moonlight, had a high value in Andean society. Wooden or stone cups could also elevate a person’s status, depending on the degree of craftsmanship and decoration. In contrast, simple or undecorated vessels were used by the common population in their daily lives or in small ceremonies during which they prayed for fertility or the benevolence of the gods.

Kerukamayoq (querocamayoc) were responsible for the production of the kerus. These specialists had an exceptional position in Andean society that came with privileges, such as exemption from farming. Even after the Spanish conquest, the production of kerus was restricted to these indigenous artisans.

In pre-Hispanic times, the decoration of Inka kerus, if there was any, consisted solely of monochromatic carved geometric patterns, for example rectangles, rhombs, triangles, and lines. A few later exceptions showed abstract figures like llamas or even faces. It is possible that there is a deeper meaning behind these designs—they may refer to religious beliefs or traditions or may have revealed details about their owner.

In pre-Hispanic as in colonial times, the keru was not a mere drinking vessel but rather a ceremonial beaker, used during rituals and political ceremonies to establish and fortify important religious, social, and political relations. It had enormous symbolic power, even after the arrival of the Spaniards. To demonstrate the divine nature of rulers, rituals were performed in public during which the Sapa Inka exchanged identical keru pairs filled with chicha (maize beer) with his “father,” the sun, in a divine toast. The symbolic power of the kerus was transferred to secular issues, so that the exchange of kerus also took place between two Andean rulers, commonly the Sapa Inka and a soon-to-be ally, to formalize an agreement.

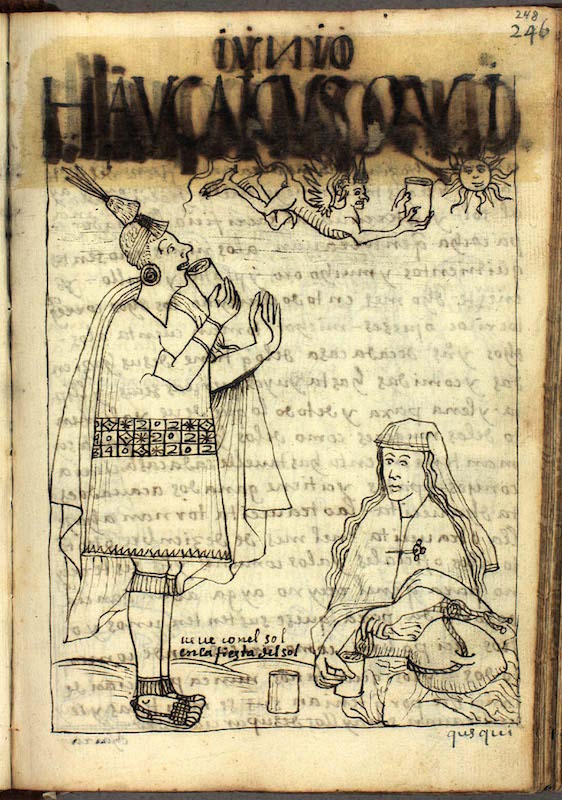

The Inka is toasting to his father, the sun. From Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government, c. 1615 (The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

With the arrival of the Spaniards in the Inka region around 1530, new pictorial conventions were introduced to the Andes. Adapting to the European traditions, traditionally abstract keru decoration began to incorporate figurative scenes. The meaning of the images may have been easier to comprehend by the new colonial society as they contained recognizable figures, symbols, and narratives. Representations of daily Andean life now appeared on the kerus, as well as newly introduced colonial rituals, such as the branding of the cattle. These images also contained symbolism only decipherable by Andean insiders, like the kerukamayoq.

A world of powerful symbolism

Let’s have a closer look at this particular Inka cup from the Brooklyn Museum. The iconography is quite common for colonial kerus. Its imagery is divided into three registers (bands)—like a comic strip. At the bottom, we see Andean flowers, likely Kantuta, which were symbolically connected to the Inka elite. Above, we find a strip with geometric patterns, similar to tocapu designs, which are also associated with Inka nobility. These designs were found on textiles as well, especially on the elaborate tunics, called unkus (also spelled uncus), of the Inka elite. As mentioned above, these motifs might have contained hidden meanings, as the Inka did not use a writing system, at least not in the strict sense of the term.

A figurative scene (image below) dominates the top register of the cup. We clearly recognize a man and a woman whose traditional apparel indicates that we are looking at representations of an Inka ruler, the Sapa Inka, and his wife, the coya. The ruler, addressing the observer in full frontal view, is wearing an unku and is crowned with the imperial headdress, the mascaypacha (also spelled mascapaycha or mascapaicha). The shield and spear in his hands characterize him as a leading warrior and are a reminder of his military power. At his side, the coya is likewise dressed in indigenous clothes, including a wrap dress (anacu) and a cloak (lliclla). The two individuals form a pair, symbolizing the complementary duality of opposites, in this case male and female, that formed Andean cosmology. As mentioned above, kerus were always produced in almost identical pairs that were then exchanged between two parties.

The figures on this keru stand under a rainbow, with light spots around and in between them, possibly depicting raindrops. Water was scarce and therefore a vital good in the often arid regions of the Andes. The rainbow thus connected the Inka with fertility and consequently with the power over life and death. Furthermore, the rainbow offered the Inka ruler a bridge to the heavenly realms as it connected the earth with Inti, the divine sun, the Sapa Inka’s father. On similar keru examples, the rainbow rises from the mouth of a feline, a frightful, strong and elegant animal that, owing to its attributes, is also associated with the Sapa Inka.

The royal pair is surrounded by potent symbols of military power, fertility, strength, and divine descent—all justifying Inka rulership. The iconography of this keru reflects its use in important religious and political rituals. While the rainbow indicates the ties between the Sapa Inka and Inti during the ceremonial toast to the sun god, the keru representation of the ruler as the leading Inka warrior with the power over life and death reminded political authorities during the official keru exchange with the Inka of the advantages, but also the possible menaces, resulting from forming or refusing alliances with the Inka.

Eliminating the threat

Portrait of Francisco Álvarez de Toledo, Viceroy of Peru, 16th century, oil (National Museum of the Archaeology, Anthropology, and History of Peru)

Over the years, the Spaniards realized that the kerus were not simple cups, but meaningful objects that continued to be used in Andean rituals. The Spanish Crown and the Catholic Church both suspected a possible threat emerging from these enigmatic vessels. For them, kerus formed part of a dangerous side of Andean culture that had to be transformed and controlled, so as not to undermine colonial rule or conflict with evangelization.

Francisco de Toledo, a viceroy of colonial Peru, gained notoriety in this context. In a time of financial struggles and continuous indigenous rebellions, Toledo carried out extensive reforms in the 1570s and 1580s to reestablish and secure Spanish royal power in the colonies. Everything Andean was viewed as a potential threat under his leadership. In the course of an extended campaign to erase any traditional indigenous beliefs and traditions, many kerus were destroyed along with other Inka objects like unkus, and the many religious figurines made of precious metals that where melted into easily transportable ingots. The kerus made of gold or silver were melted down, but wooden vessels survived, mainly because the cups were very popular in colonial society. Like modern souvenir hunting, Europeans loved these “indian” vessels and ordered their production for personal use, gifts, or trade.

Unfortunately, this love for the exotic endures today, so that kerus form a large part of the objects sold on the black market. The relatively few cups remaining for the use in a scientific context are spread all over the world in the different museums and collections. Unfortunately, many of the wooden examples have deteriorated over time. The exceptionally well-conserved keru at the Brooklyn Museum therefore represents a precious example and provides us with insights into a complex and fascinating society.