Congo Square, New Orleans, Louisiana (photo: Southernbelle1628, CC BY-SA 4.0)

New Orleans, like many cities all around the world, is dotted with metal plaques marking sites associated with pivotal events or important figures. Visitors walking along Rampart Street and into Louis Armstrong Park will encounter one of these large red signs that deviates from this formula, commemorating neither a singular individual nor a specific date in history. Rather, the marker identifies the location where enslaved and free persons of African descent gathered for weekly community-building performances beginning in the 18th century.

Termed Congo Square, the communal activities undertaken here by largely unidentified artists gave rise to the greatest musical traditions of the United States: ragtime and jazz.

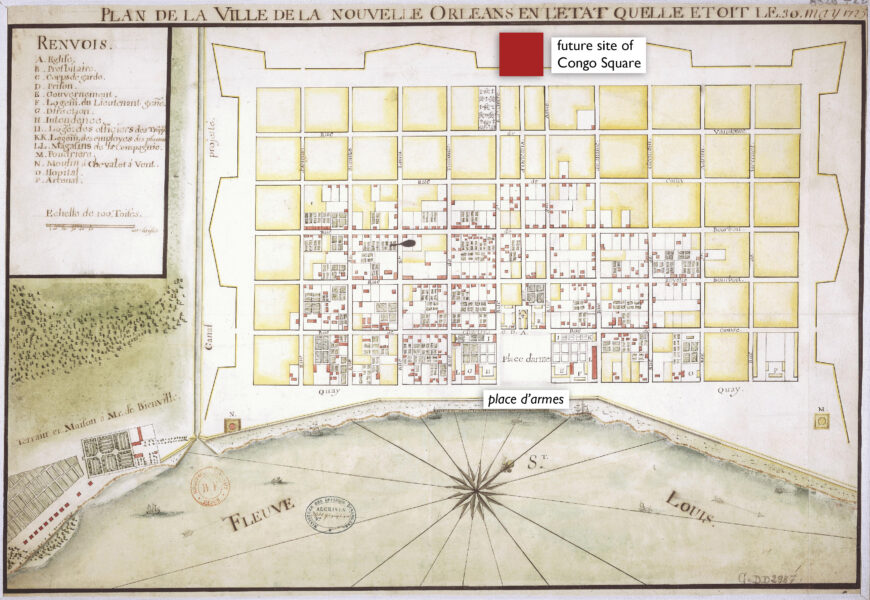

“Map of the City of New Orleans as it was on May 30, 1725,” 1725 (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

New Orleans

New Orleans became part of the United States in 1803 when the government bought the entire French colony of Louisiana (New Orleans was the capital). Nearly a century prior, in 1718, the French naval officer Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville had established a colony in the swamp at this bend in the Mississippi River where it flows into the Gulf of Mexico. European settlers drove out the original inhabitants, members of the Choctaw and Chitimacha nations, and began importing enslaved Africans to provide free labor shortly thereafter. The 1725 map above by an unknown cartographer shows how the newly established city of New Orleans appeared just a few years later. Built on a uniform, rectangular grid system, the town was protected by a narrow retaining wall and had a place d’armes (public square) that opened onto the river. Many of the buildings were for colonial administration (such as the prison and military barracks) and religious functions (such as the church and hospital).

A market where enslaved Africans could sell items including foodstuffs and small manufactured goods quickly developed just outside the city’s walls. What was initially a way for enslavers to shirk their legal responsibilities of feeding and clothing those held in forced labor—termed the Code Noir—eventually became a source of income and economic power for Africans and free people of color under French and Spanish rule. In 1760, during the middle of the so-called French and Indian War, New Orleans military engineers extended the boundaries of the city, bringing the market within the city limits. After the United States purchased Louisiana from the French government in 1803, these walls were dismantled allowing for further expansion.

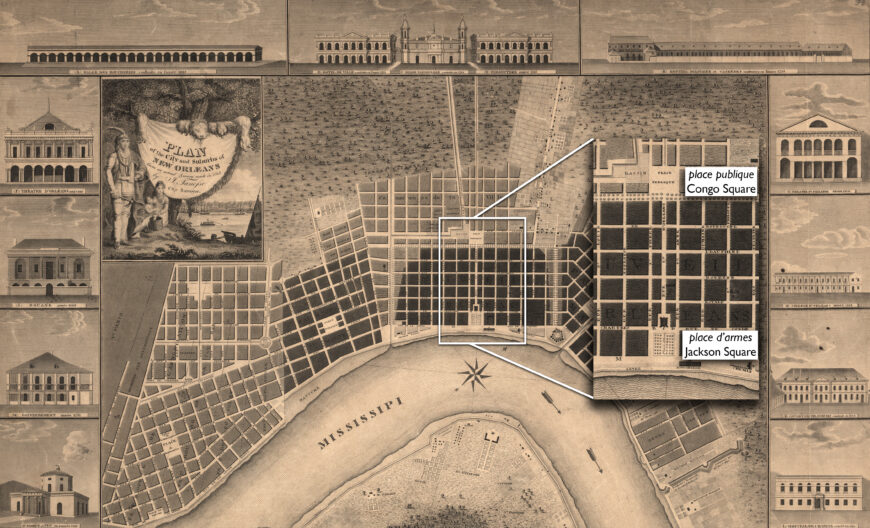

Williams Rollinson, “Plan of the city and suburbs of New Orleans: from an actual survey made in 1815,” (New York: Charles Del Vecchio, 1817) (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

In the map above, this market was labeled as place publique (Congo Square today), located just a few blocks north of place d’armes (Jackson Square today). By 1815, when this map was made, this area on the outskirts of the city had become a well-known gathering place for enslaved Africans and free people of color in both the immediate urban area and the surrounding plantation environs. These Sunday convenings quickly expanded from commercial activities into opportunities to spend time with friends and relatives, to exchange news, and—most notably—to maintain musical and dance traditions from their homelands as well as develop new forms of artistic expression. New Orleans’ Black community is unique insofar as the ethnic composition of its inhabitants in the early years of colonization was relatively homogenous, with the majority of the enslaved population arriving from the same general area in Central Africa, and often spoke the same language, namely Bambara. Following the Haitian Revolution in 1791 and the occupation of the island of Cuba by the United States shortly thereafter, refugees—both free and enslaved—from these conflicts arrived in New Orleans. By 1848, the year that slavery was abolished in France, the majority of enslaved people in New Orleans had been born in the colony, rather than in Africa or the Caribbean. The square’s name derived from its association with Afro-descended people, colloquially referred to as Kongos despite the ethnic diversity outlined above, as well as the arrival of the so-called Congo Circus led by Cuban man referred to as Monsieur Gaetano.

Written accounts and early illustrations

Written accounts of these performances by European colonists appear almost immediately after the founding of the city itself. The earliest reference occurs in Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz’s Histoire de la Louisiane, a memoir of the nearly two decades he spent in Louisiana between 1718 and 1734. He stated: “In a word, nothing is more to be dreaded than to see the negroes assemble on Sundays, since under pretense of Calinda or the dance, they sometimes get together to the number of three or four hundred, and make a kind of Sabbath….” The French words calinda and bamboula were used as catch-all terms to refer to Afro-Caribbean performances, sometimes conflated with the religious rituals associated with Vodùn.

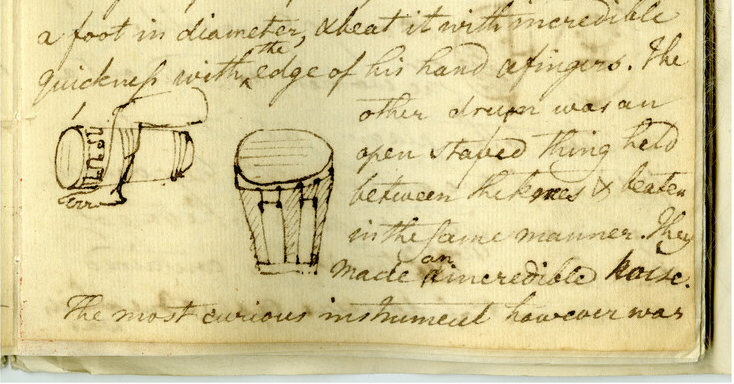

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Page 31 from Journal IV, February 1819 (Maryland Center for History and Culture, Baltimore)

While the term calinda referred to both the martial art and the music accompanying it, the bamboula is associated with transverse drumming—that is, the drums are lying on their side, the drummers sitting astride them, sometimes pressing one heel on the drumhead to change the pitch. The British architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe recorded his observations of the activities in the square in his journal entries during the month of February in 1819. He described the arrangement and included illustrations of so-called bamboula drums, writing that, “one drummer placed a drum on the ground and sat upon it as he played.” Eventually, the latter term—referring to both the small drum and the syncopated musical cadence developed by enslaved Africans trafficked to the Americas—gained popularity.

The preponderance of written commentary about the activities in Congo Square appearing after 1803 is due to the cultural differences between Anglo-American settlers and French and Spanish colonial authorities and their Creole descendants. Roman Catholics’ exuberant secular celebrations and acceptance of ritual in liturgical activities stands in sharp contrast to Protestants’ repressive socio-religious norms. This rigidity extended to the treatment of enslaved persons: the severe regulation and restrictions upon the activities of Black residents prevalent elsewhere in the United States arrived in the Crescent City in 1856 when the new city council adopted an ordinance making it illegal to beat a drum or blow a horn. While impossible to suppress, these regulations caused gatherings to relocate outside the city limits.

The writings of George Washington Cable and Lafcadio Hearn were influential in spreading awareness about cultural heritage of Black New Orleanians. Hearn’s essay, “The Scenes of Cable’s Romances,” published in the November 1883 issue of Century offers some valuable information and attests to the diffusion of the so-called Congo Dances:

Congo Square, the last green remnant of those famous Congo plains, where the negro slaves once held their bamboulas. […] Every Sunday afternoon the bamboula dancers were summoned to a wood-yard on Dumaine Street by a sort of drum-roll, made by rattling the ends of two great bones upon the head of an empty cask; and I remember that the male dancers fastened bits of tinkling metal or tin rattles about their ankles, like those strings of copper gris-gris worn by the negroes of the Sudan.Lafcadio Hearn in “The Scenes of Cables Romances” [1]

While undoubtedly exaggerating his own powers of recollection—Hearn lived in New Orleans for just two years as a child—his emphasis on the characteristics of the accouterments of the performers is valuable.

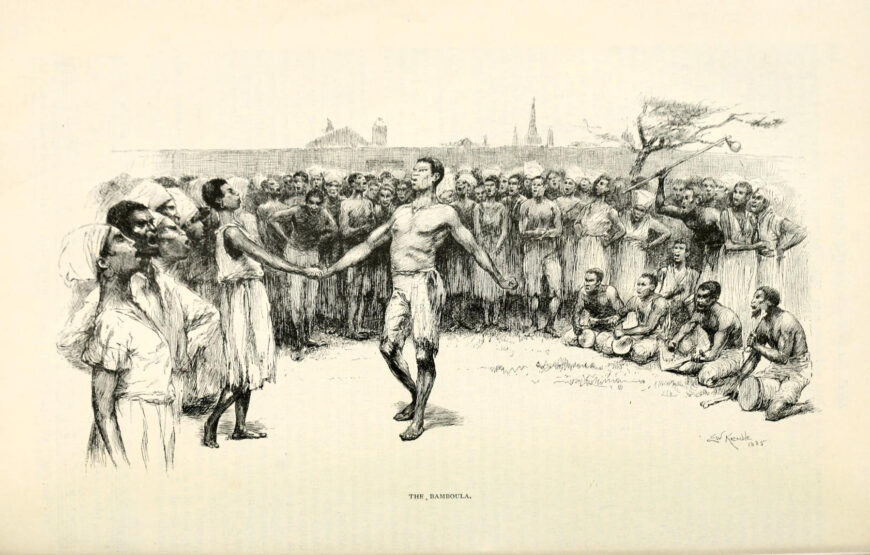

Edward Windsor Kemble, “The Bamboula,” 1886, photomechanical print. First reproduced in George Washington Cable, “The Dance in Place Congo,” Century, volume 31, number 4 (February 1886), p. 524

When E.W. Kemble created the lithograph above in 1886, these gatherings were already in the process of transforming. Combining elements of the accounts of Cable, Hearn, and their predecessor Latrobe, the central couple are encircled by a ring of participants whose mouths are open in song. Immediately above the four crouching drummers on the right of the composition is another figure, his right arm raised in exhortation and wielding a long staff with a gourd attached to the end. The drummer at the far left of the circle closest to us appears to be holding a femur bone, while the church spire and the roof of the town hall seen in the background above the wall situate us firmly within the city.

Kemble was a successful illustrator specializing in pen and ink caricatures. Today he is perhaps most well known as the illustrator for Mark Twain’s 1884 novel Huckleberry Finn and Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus—both notable for their racist portrayal of Afro-Americans. Kemble’s depictions of Black Americans and newly arrived immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe were reproduced widely in serial publications such as Life and Century, and thus contributed to the normalization of dehumanization of non-white people. Kemble’s depiction of the so-called bamboula remains ambiguous—the open mouths of the participants and their energetic gestures edging just up to the line between satire and caricature, with only variations in attire and skin color to differentiate the participants from one another.

An area transformed

Unfortunately, little archaeological evidence of these gatherings remains today due to the extensive degree of landscaping following the end of the U.S. Civil War to transform the area into a public park. After the conclusion of the Civil War, the Southern Railroad laid down tracks alongside Carondelet Canal, further limiting Black residents’ access to the park. In 1897, the city created a so-called red-light district, Storyville, adjacent to the area in a futile attempt to control and contain sex work. At that time, the space was renamed Beauregard Square after General P.G.T. Beauregard, a leader of the Confederacy, as part of a large-scale campaign to maintain white supremacist social hierarchy by valorizing those who fought for slavery—and in which Kemble took part. In the late 1920s, the area was rezoned and demolished to make way for a public performing complex but the project was abandoned during the Great Depression. City officials were largely unable to regain momentum for the municipal resource until 1971, at which point they were galvanized by the death of Louis Armstrong, one of the city’s most influential native sons whose popular jazz music traces its roots to this very place. The name was officially changed to Congo Square—its more popular name—in 2011.