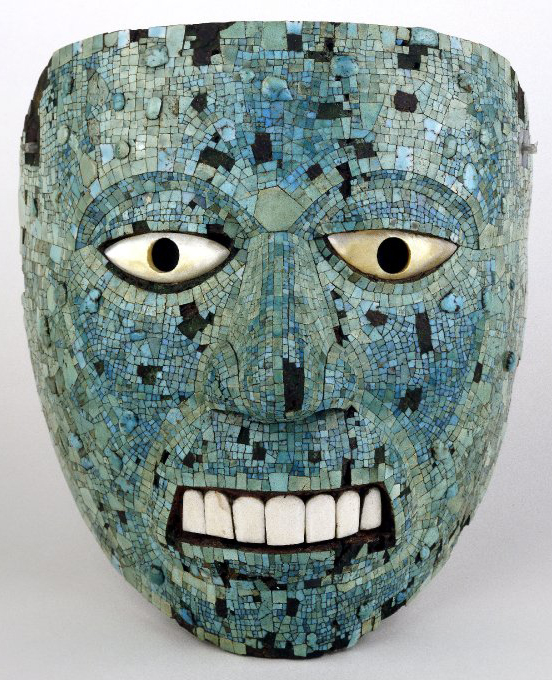

Turquoise mosaic mask (human face), 1400-1521 C.E., cedrela wood, turquoise, pine resin, mother-of-pearl, conch shell, 16.5 x 15.2 cm, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum

During the twelfth century C.E. the Aztec (or Mexica*) were a small and obscure tribe searching for a new homeland. Eventually they settled in the Valley of Mexico and founded their capital, Tenochtitlan, in 1345. At the beginning of the sixteenth century it was one of the largest cities in the world.

The Mexica were a migrant people from the desert north who arrived in Mesoamerica in the 1300s. This previously nomadic tribe was not welcomed by the local inhabitants who viewed them as inferior and undeveloped. Legend tells that as a result the Mexica wandered waiting for a sign to indicate where they should settle. It is said that in 1325 C.E. this sign, an eagle and serpent fighting on a cactus, was seen at Lake Texcoco prompting the Mexica to found their capital city, Tenochtitlan.

Tenochtitlan

The Aztec capital city, Tenochtitlan, was founded on a small piece of land in the western part of Lake Texcoco. The city was contained within high mountains and surrounding lake and marshes. To create living and farming space the Aztecs sank piles into the marshes and formed small land masses called chinampas, or floating gardens. Tenochtitlan was highly developed with causeways between islands for transport, aqueducts to carry fresh water and sewers to dispose of waste. The city developed into a metropolis led by a ruling leader and supported by noble classes, priests, warriors and merchants. By the early 1500s it contained an array of pyramids, temples, palaces and market places.

Mexica capital city, Tenochtitlan © Trustees of the British Museum

By 1430 C.E. the Mexica had assimilated aspects of the surrounding tribes and developed into a structured society. Their military became powerful and campaigns were fought and won. The Triple Alliance was created with the lords of Texcoco (situated on the eastern shores of Lake Texococo) and Tlacopan (sometimes referred to as Tacuba, situated on the western shores of Lake Texococo) further strengthening Aztec power.

A huge empire

Empire of Moctezuma II in 1519 © Trustees of the British Museum

Warfare was extremely important for the Mexica people and led them to conquer most of modern-day central and southern Mexico. They controlled their huge empire through military strength, a long-distance trading network and the tribute which conquered peoples had to pay. The Mexica went to war for two main reasons; to exact tribute and to capture prisoners. They needed prisoners because they believed that the gods must be appeased with human blood and hearts to ensure the sun rose each day. Conquering new regions brought the opportunity to capture slaves who were an important part of Mexica society. Under a succession of rulers armies were sent further across Mexico. By the start of the 1500s the Mexica empire stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific and into Guatemala and Nicaragua.

The Mexica designed roads for travel by foot because there were no draught animals. These roads were well maintained and boosted trade both for the Mexica and for the tribes under their control. They also enabled the Aztecs to be informed of events across their empire. The Mexica exported luxury items such as jewelry and garments manufactured from imported raw materials. They also exported goods such as lake salt and ceramic goods. Exotic luxuries such as animal skins, feathers, rubber and jade came from the distant southern tropics. Beautiful manufactured goods such as jewelry, textiles and pottery came from craft centers, a famous example of which is Cholula (in the modern Mexican state of Puebla). Traded goods even came from as far away as southern New Mexico and raw materials from Central America appeared in the markets of Tenochtitlan.

Complex religious beliefs

Stone sculpture in the British Museum collection reflects the Mexica’s complex religious beliefs and the large pantheon of gods they worshipped. Their sophisticated ritual calendar reflected the rhythms of the agricultural year and their ceramic sculptures are noted for their visual impact. Musical instruments such as drums were decorated with intricate carvings, probably because of the importance of music during Mexica rituals.

Seated figure of Mictlantecuhtli, c. 1325-1521 C.E., Mexica, sandstone, 60 x 27 cm, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum

This sculpture represents Mictlantecuhtli, an Aztec god associated with death. It is made from a sandstone which is not found in the Mexican highlands and was probably obtained in Veracruz. The figure bears three glyphs, carved on his back: “Two Skull,” “Five Vulture,” and “Four House.”

Mictlantecuhtli, and his counterpart Mictlancihuatl, inhabited the lowest of the nine levels in which the Underworld (Mictlan) was divided. The “soul” of the deceased went to a particular level in Mictlan according to the circumstances of their death. Those who died of natural causes went to the ninth level and had to negotiate all sorts of obstacles to reach it. To help the “souls” in their dangerous journey the deceased were cremated with some of their possessions, especially the tools they used in life.

Two spectacular ceramic figures of Mictlantecuhtli were recovered in the 1980s from the “House of the Eagles,” a building located in the Sacred Precinct of the Mexica capital, Tenochtitlan. These colossal figures had traces of blood on them. This is consistent with depictions in the codices (screenfold books) of ceremonies in which an image of Mictlantecuhtli, or a person representing him, is bathed with blood.

Craftsmen also worked in gold, turquoise mosaic and feathers. Most pieces were destroyed by the Spanish invaders, but the British Museum holds a number of turquoise mosaics, the most beautiful of which were produced by Mixtec craftsmen and sent to the Mexica as tribute.

Spanish rule

Hernán Cortés and his small Spanish army arrived in 1519 and overthrew the Mexica ruler Moctezuma Xocoyotzin with relative ease. This was partly due to the latter’s weakness, as well as the Spaniards’ superior weaponry, their unfamiliar battle tactics and the devastation of the Mexica population by European disease. Mexico remained under Spanish rule until gaining independence in 1821 C.E.

*The people and culture we know as “Aztec” referred to themselves as the Mexica (pronounced ‘Mé-shee-ka’).

© Trustees of the British Museum