Cabán group, Los Reyes Magos, c. 1875–1900, carved and painted wood with metal and string, 20.7 x 30.3 x 15.3 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.)

Who accompanied the jíbaro’s prayer in the isolated mountains of 19th-century Puerto Rico, when roads made it difficult to reach the nearest church and few priests braved them to comfort the rural faithful? They turned to devotional practices that did not call for official rituals and created household altars to the Catholic saints and the Virgin Mary. These were built around santos de palo (wooden saints), religious carvings made by artisans in their communities. This small wooden sculpture of the three Magi as horsemen is representative of a sculptural tradition that sprung from the necessities of local devotion.

A Puerto Rican take on the Three Kings

The Three Kings, or Magi, are important figures in Christianity and in the European tradition are considered rulers from kingdoms in Arabia, Africa, and Asia who arrived at the manger where the Christ child was born to adore him as the son of God. Measuring a little more than 8 inches in height, this wood sculpture features the kings (named Gaspar, Melchior, and Balthazar) sitting on carefully carved horses, one beside the other facing the same direction. The horses’ long, delicate legs are fixed to a short rectangular base painted a dark green. All three are individually carved and colorfully painted, draped in capes and wearing crowns.

Left to right: Gaspar, Melchior, and Balthazar (detail), Cabán group, Los Reyes Magos, c. 1875–1900, carved and painted wood with metal and string, 20.7 x 30.3 x 15.3 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.)

The Kings each have similar, impassive faces with short black beards and wear the same garments. Following Puerto Rican tradition, Melchior is represented as a Black king on a white horse at the center. [1] This contrasts with the European tradition of representing Balthazar as the Black African Magi. He wears a red cape, while Gaspar and Balthazar wear a white and green one. Astride on their horses with arms slightly outstretched, they may have held their distinct attributes, their kingly gifts of myrrh (Balthazar), frankincense (Melchior), and gold (Gaspar), in their now empty or missing right hands. In their left hands they hold what seem to be maracas.

Their bodies are rather geometrical, with almost triangular upper torsos and cylindrical extremities. This economy of design, emotion, and iconography is typical of the santos de palo tradition. Artisans were interested in more simplified representations of religious figures, developing a bulky and symmetrical style not preoccupied with naturalism but rather with easy identification and an emotional distance that could emphasize the divine nature of the subject. [2] This responds well to the santos’ function: private worship in small dwellings for those familiar with the subject matter. This piece also demonstrates the adaptation of established religious imagery to local culture, with the addition of musical instruments like maracas, tambourines, and guitars. [3] The Magi as musicians is not uncommon in Puerto Rico and may be a reference to the festivities of Three Kings Day’s eve.

Melchior (detail), Cabán group, Los Reyes Magos, c. 1875–1900, carved and painted wood with metal and string, 20.7 x 30.3 x 15.3 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.)

The need for “santos de palo” and the beginnings of a tradition

The images of religious figures as symbolic representations that assist the faithful in their worship has long been an important aspect of Christianity. They are prominent in Catholicism, where the representations of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints serve as reminders of their stories and their qualities worthy of emulation. Mary and the saints are also regarded as intercessors between the faithful and God, which makes their images important to many practitioners. The creation of these santos for domestic worship in Puerto Rico began under Spanish rule, well into the colonization process and flourishing during the 19th century as population numbers grew in the mountainous regions. [4] Catholicism was the dominant religion, and with its churches and monasteries came the need to acquire religious imagery for them.

The earliest Christian objects were brought from Spain, either by private individuals or clerics. From the 16th to the 18th century, a lack of funds and fluctuations in commercial relations with Spain and other Spanish colonies could make acquiring devotional artworks difficult. It could take years to receive a religious painting or sculpture commissioned from an artist in the metropolis. For reference, between 1651 and 1662 no Spanish commercial ship was recorded as having stopped in Puerto Rico to unload goods. [5]

José Campeche, Exvoto de la Sagrada Familia (Exvoto of the Holy Family), late 18th century, oil on panel, 25.6 x 20.4 cm (San Juan, Puerto Rico, Colección Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña)

Devotional images needed to be produced locally. It’s likely that members of religious orders with some artistic instruction produced some devotional works early on, with local craftsmen being commissioned as time went by. The emergence of local artists like painter José Campeche and sculptor Felipe Neri de la Espada in the late 18th century contributed to religious works of finer quality, often destined for churches and convents. These spaces, particularly those with more income for the purchase or commission of artworks, were concentrated in developed areas like the capital San Juan and the southwestern town of San Germán.

Puerto Rico was primarily rural well into the 20th century, with most of the population living outside urban centers. This, combined with a lack of safe roads, isolated a considerable part of the rural population from these official places of worship, but distance fostered a creative solution among the devotees in the mountains. [6] Santeros took up the job of creating the religious images their neighbors needed, tailored to their particular devotions and imbuing their sculptures with local character.

The Cabán family of santeros

This Three Kings sculpture comes from the Cabán family. The Cabán’s produced at least four generations of santeros, who lived and worked mainly in the northwestern towns of Aguada, Camuy, and Aguadilla. Eduviges Cabán (1818–91), his son Quiterio Cabán (1848–1941), and grandsons Florencio (1876–1951) and Manuel Cabán (1884–1962) are some of the most well-known artisans of the family.

Print showing Our Lady of the Rosary, a popular subject of santos de palo. José María Martín, Virgen del Rosario, 1805, intaglio (Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid)

Like other santeros, they were self-taught craftsmen who relied on accessible and cheap lithographic prints and illustrated prayer cards as references for their sculptures and their iconography. [7] In the case of the Cabán family, the profession and knowledge were passed down through the generations, and it’s likely santeros taught others regardless of familial relations, as formal workshops for this craft did not exist. [8] Signing pieces wasn’t common practice at least before the 20th century. Their sculptures were mostly in the round and carved in local woods with household implements, like pocket-knives. [9] While often commissioned by members of their communities, many artisans also sold their wares door to door, in markets, and in the streets. [10] For many, like Florencio Cabán, this was their main source of income even if they took up other types of work. [11] Santos tended to be small in size in line with their household setting, with miniature works reaching only 4 inches in height, though most tend to be between 4 and 15 inches. [12]

Milagros around Balthazar’s wrist (detail), Cabán group, Los Reyes Magos, c. 1875–1900, carved and painted wood with metal and string, 20.7 x 30.3 x 15.3 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.)

Puerto Rican santos represent a myriad of Christian figures, from the Holy Trinity (God the Father, Christ, and the Holy Spirit) to the angels and saints. The Virgin Mary and the Three Kings are the most popular subjects, exemplifying the devotional preferences among the jíbaros. [13] Rosaries were prayed and promises made before the sculptures—devotion and offerings in exchange for good health and help with the vicissitudes of life. It was common to present milagros, also called ex-votos, which were little votive offerings often in metal representing a body part affected by illness or injury. They were often put on the santos, as seen on the wrist of one of the Kings.

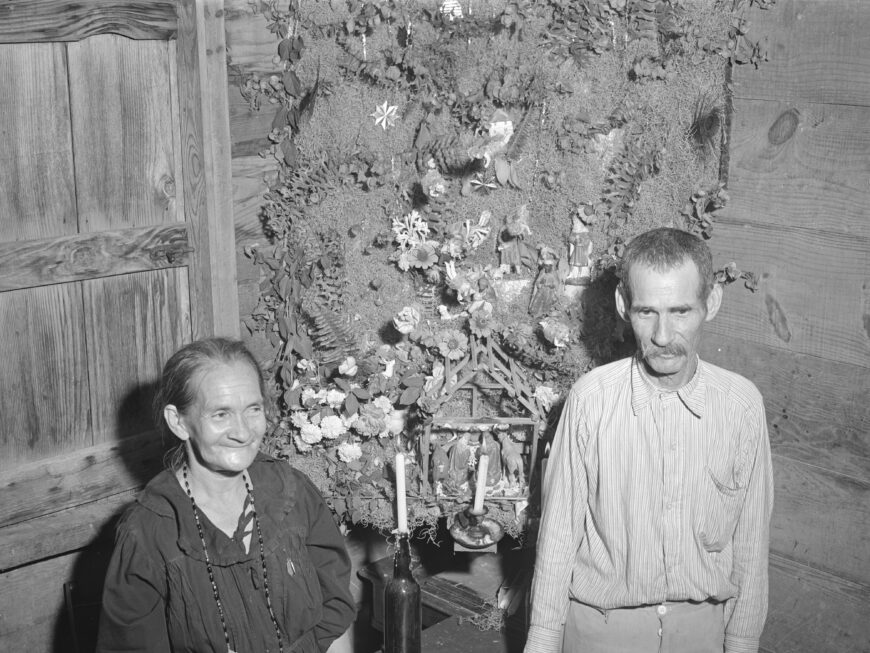

Hosts of Velorio de Reyes party with their shrine. Jack Delano, Tenant farmer and his wife at whose home a Three Kings’ eve party was held, 1942, Guánica, Puerto Rico (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

Santos were incorporated into religiously significant celebrations and nativity scenes, cleaned and repainted by their custodians for festivities. Epiphany eve, the 5th of January, was especially important. Velorios de Reyes (Three Kings’ nightwatch) would see the construction of elaborate shrines with palm fronds and flowers in people’s houses with neighbors gathering to sing, pray, and eat on the night of the 5th as they waited for the Kings to arrive.

Left: Unidentified artist, Our Lady of Sorrows santo, c. 17th–19th century (Philippines), ivory (Intramuros Administration, Manila); right: Unidentified artist, Our Lady of Sorrows santo, c. 17th–18th century (New Mexico), painted wood, 36.9 x 17.8 x 7 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art)

This type of sculpture, artisanal religious images tailored to local customs, is not unique to Puerto Rico. We find a similar production in the Philippines and New Mexico, with some stylistic and ritual differences. The santos tradition in the Philippines produced elaborate pieces for churches in rich materials like ivory. In New Mexico, the santos have more similarity with Puerto Rican tradition though they tend to be more stylized figures. These santeros also produced images for churches and moradas, though many of the smaller ones were for private devotion as well.

The arrival of cheap plaster cast images in the late 19th century, the spread of Protestantism with the United States’ invasion in 1898, and the mass migrations from the countryside to the city (and to the U.S.) throughout the first half of the 20th century had a transformative effect on the santos de palo tradition. Their production and related traditions diminished considerably by the mid-1900s. In the 1950s, a cultural and political movement in Puerto Rico sought to research and preserve local customs to prevent their loss. The founding of the Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña in 1955 was a direct result of that effort, along with a renewed interest in santos de palo. Once important objects of religious worship, they are now regarded as important examples of folk art and as emblems of Puerto Rican culture, attracting collectors and inspiring today’s santeros to produce works that establish dialogue between the past and contemporary culture.