Curved Pick Bannerstone, Glenn Falls, New York, 6,000–1,000 B.C.E., banded slate, 2.7 x 13.6 cm (American Museum of Natural History DN/128)

Why is it that in schools across the United States we learn about the ancient Egyptians and Greeks and Chinese, but not about the ancient people of North America? In the Eastern half of the United States between 6000 and 1000 B.C.E., in a period known as the Archaic, thousands of nomadic Native Americans travelled and lived along the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. Amongst the art they made and left behind are enigmatic, carefully carved stones known today as bannerstones. They are generally symmetrical in shape and drilled down the center, leading 19th-century archaeologists and collectors to assume that these uniquely carved stones were placed on wooden rods hoisted in the air as “banners.” Today we are far less certain why they were made or how they were used, nonetheless we still call them bannerstones.

Curved Pick Bannerstone, Glenn Falls, New York, 6,000–1,000 B.C.E., banded slate, 2.7 x 13.6 cm (American Museum of Natural History DN/128)

Bannerstones, like the slate Curved Pick from Glenn Falls, New York, are carefully chosen stones that were then carved, drilled, and polished compositions. At the center of this particular stone, an Archaic sculptor carved a small ridge that marks and accentuates the off-white markings left by a worm or some other biologic element to form what is known as a trace fossil embedded into the sedimentation of the rock as it formed. The sculpted ridge and white fossil traces cross over and through the symmetrical dark natural banding of the slate (the slate was formed by two geologic processes, a sedimentation process and then a metamorphic process). Each different color of the banding from the light brown to the dark brown indicates a different layer of sedimentation hardened into the rock structure.

Curved Pick Bannerstone (reverse), Glenn Falls, New York, 6,000–1,000 B.C.E., banded slate, 2.7 x 13.6 cm (American Museum of Natural History DN/128)

On the other side, the banding of the stone forms a noticeably different pattern, making this a naturally occurring slate with different sedimentary patterns on either side of the stone that further attracted and challenged the sculptor to compose both sides into a single complex composition with the curved form of the sculpted bannerstone echoing and accentuating the concentric forms of the dark banding. Given that slate is a relatively soft stone and easier than other stones to shape and drill, it is one of the most common stones chosen by ancient Native North Americans for the making of bannerstones, especially in the Ohio Valley.

Curved Pick Bannerstone (top), Glenn Falls, New York, 6,000–1,000 B.C.E., banded slate, 2.7. x 13.6 cm (American Museum of Natural History DN/128)

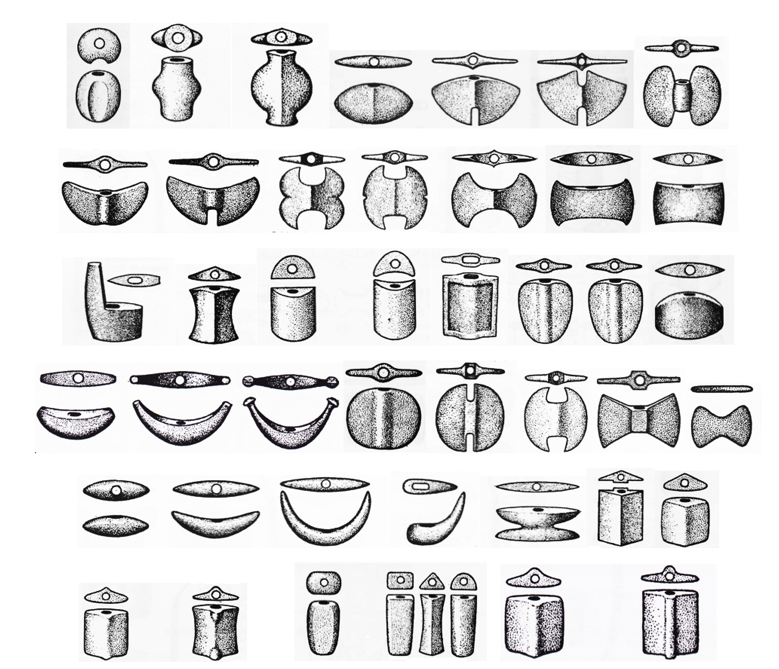

Once the raw stone was found river-worn or quarried from a mountainside, the sculptor would take a harder stone known as a “hammerstone” to begin to peck and then grind the banded-slate, modeling their work on one of twenty-four distinct bannerstone types modern-day scholars have defined in our studies of these ancient Native American artworks.

Choosing the Curved Pick type, one of several bannerstone forms particular to the Northeast, the sculptor worked their composition to be precisely centered on the two different faces of the banded slate, grinding the “wings” into a raised edge that runs through the dark slate bands, and flattening, shaping, and smoothing the surface around the perforation, further individualizing their finished work. The individuality of each bannerstone in relation to recognizable forms, recognizable to the Archaic sculptor and to those of us studying these stones today, is an intrinsic component of their making and meaning.

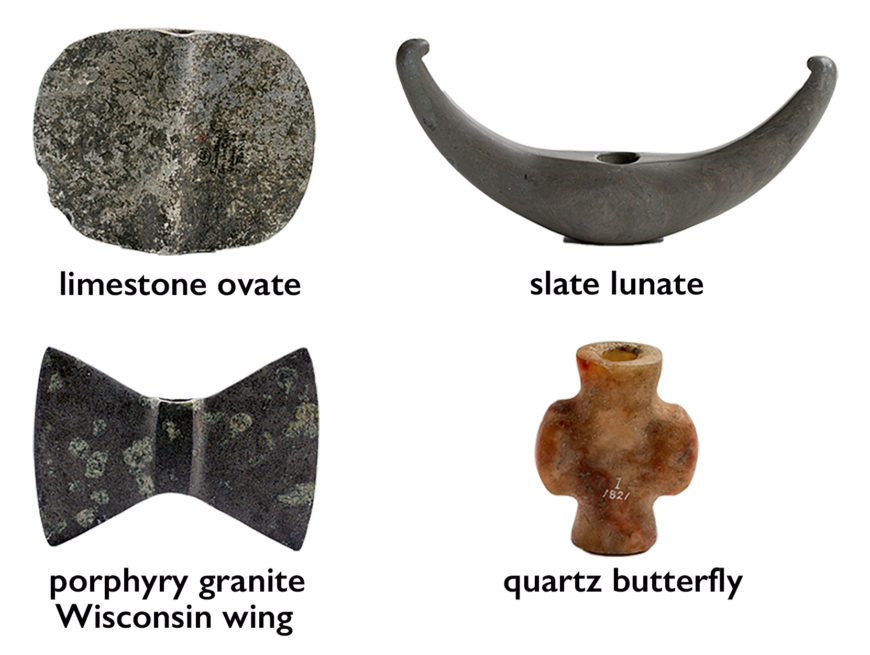

Different types of bannerstones (clockwise from left: American Museum of Natural History d/144 Limestone; American Museum of Natural History 13/105 Slate; NMNH A26077 Porphyry Granite; American Museum of Natural History 1/1821 Quartz)

Bannerstones were made from many types of stone including those that are sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous. The sedimentary rock that we see in a limestone ovate bannerstone is the softest, while slate (a metamorphic stone) shows more signs of natural geologic transformation such as banding that we see in a lunate bannerstone. Igneous rock is the hardest and often has embedded elements from various minerals when magma first bubbled up from the core of the earth and cooled. This kind of complex igneous surface is evident in a porphyry granite Wisconsin wing bannerstone. Some bannerstone (like the quartz butterfly) are made out of even harder material made of minerals and crystals that would have been even more time consuming and challenging to carve. The relative hardness of the stone chosen by the sculptor would have an impact on the kinds of bannerstone forms they would or could sculpt. The thin wings of slate and even granite bannerstones could not be carved out of quartz, while the seemingly thick rounded form of a Quartz Butterfly bannerstone might appear unfinished if it were carved in slate.

Southern Ovate Preform Bannerstone; Habersham County, Georgia, 6,000 – 1,000 B.C.E., igneous, coarse-grained alkaline, 11.5 x 10.3 cm (American Museum of Natural History 2/2205)

Unfinished bannerstones

Whatever their shape or relative state of completion, all bannerstones were made using river-worn pebbled hammerstones to peck, grind, and polish the surface. Some bannerstones, however, were intentionally left in a partial state of completion known as a “preform” such as a Southern Ovate from Habershan County, Georgia.

Southern Ovate Preform Bannerstone; Habersham County, Georgia, 6,000 – 1,000 B.C.E., igneous, coarse-grained alkaline, 11.5 x 10.3 cm (American Museum of Natural History 2/2205)

Southern Ovate Preform Bannerstone; Habersham County, Georgia, 6,000 – 1,000 B.C.E., igneous, coarse-grained alkaline, 11.5 x 10.3 cm (American Museum of Natural History 2/2205)

This bannerstone is partially drilled at the spine on one side with a hollow cane or reed that grow along the banks of rivers, and undrilled at the other side. The reed itself is hollow and when rubbed briskly between the hands with the application of water and some sand, can drill through slate, granite and even quartz. With this stone the partial passing of the reed leaves concentric circles on the inside of the perforation and a small nipple visible here that would fall out the other side when the perforation was complete. The medium to coarse-grained igneous rock is left unpolished, just as the ovate form and perforation are left unfinished. Scholars believe that preforms such as these were often buried in this state, or meant to be finished at a later date by another sculptor in a different location. The kind of granite we see here is unique to this region of the Southeast and so would likely have been valuable as a trade good further west along the Mississippi where there was little or no stone available. By partially completing the Ovate form, even partially drilling the perforation the sculptor of this southeastern stone increased the value of the stone while leaving the finish work to whomever acquired this Ovate in this preform state.

Possible uses and meanings

In the early 20th century archeologists sought to define a specific use for bannerstones, including theories of them as sizers placed between the knots of fishing nets or as weights placed on the wooden shafts of throwing sticks for hunting known as atlatls, a tool used for thousands of years to extend the flight and thrust of a spear well before the invention of the bow and arrow. [1] These interpretations raise as many questions as they may appear to answer. They do not explain away the making and importance of these finely sculpted and polished bannerstones, many of which are too fragile, too small, or too large to be used as net sizers or hafted onto an atlatl. Beyond the excavating and explaining, bannerstones remain exquisite individual sculptural expressions that were made and valued for over 5,000 years. Inexplicably, after 1000 B.C.E. bannerstones were no longer made nor did they live on as actively used lithics or as heirloom objects of successive Indigenous communities, pointing to their specific importance within a particular place and time. What they meant to the bannerstone makers and the community of people who saw and valued them and why they stopped making them remains elusive, unknown, or unknowable. In the realm of the everyday, with their perforated holes meant for some kind of assemblage, what did they adorn? Did people wear bannerstones on their bodies or hoist them in procession? We do know what people did with them beneath the ground, where they carefully buried bannerstones in caches, or with great intention they buried them with their dead. Many of these bannerstone makers and their communities were nomadic, mindfully leaving these bannerstones in the ground, anchoring something of themselves as they seasonally left and returned with an echo of their placement in their memory.

NAGPRA

Since Webb’s 1936 excavation at Indian Knoll, Kentucky, remains and belongings of Native Americans are no longer simply there for the taking for the collector’s shelf, college laboratory, or museum case. Especially with the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (known as NAGPRA), funerary remains of Native Americans (bodies and objects placed with these bodies in burials) are protected from being disturbed or excavated unless permissions have been granted by Native communities culturally affiliated with the burials. [2] Native American funerary objects already in federal agencies or museums and institutions that receive federal funding are to be made available to culturally affiliated communities that have the right to request their repatriation. Whatever the aims of post-Enlightenment science or the elucidating potential of the exhibition of artworks may be, these ideological motivations must be negotiated with and in light of the desires, memories, practices, and philosophical underpinnings of the Native American people and their descendants who often buried their dead with bannerstones and other burial remains.

Currently the William Webb Museum has recently removed all photographs of the 880 burials and 55,000 artifacts that Webb excavated at Indian Knoll in 1936 and will no longer allow scholars to study these remains “until legal compliance with NAGPRA has been achieved.” What “legal compliance with NAGPRA” specifically means for the remains including bannerstones excavated at Indian Knoll is profoundly complex. No living communities of Native Americans trace their direct line (in legal terms, known as “lineal descendants”) to the Archaic people who built this shell mound in which they buried their dead along with valued objects including broken and unbroken bannerstones. With the ratification of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Shawnee and Chickasaw communities that lived in Western Kentucky in the 19th century were forced to move west to Oklahoma. [3] How the William Webb museum will choose to adhere to NAGPRA and what they will do with burial remains from Indian Knoll will set a precedent unfolding into the present about how to collaborate with living Native American communities (even those who are not “lineal descendants”), and how to mindfully regard the past lives of the Ancient people of North American, their human remains along with the multitude of things they made, valued, and arranged in and outside of burials.

Intentionally broken?

Since the 19th century, many bannerstones were found in ancient trash piles known as “middens” as well as ritual burials of things known as “caches” and many more in human burials in subterranean or earthen mound architecture. A large number of bannerstones have also been found broken in half at the spine where they are most fragile due to the thin walls of the drilled perforations.

Kill hole in the center of a plate with a supernatural fish, 7th century, Late Classic Maya, earthenware and pigment, 10.5 x 40.6 x 40 cm, Guatemala (De Young Museum)

The intentional nature of these acts of breaking are evident in the placement of pieces together with no sign of wear along the broken edges, carefully arranged with other valuable objects. Archaeologists and historians of the ancient art of the Americas amongst the 8th century-Maya (of Mesoamerica) or 12th-century Mimbres art (of what is today the southwestern U.S.) have often identified this practice as “ritually killing” the object before burial. Though these bannerstones in most cases were intentionally broken by the very people who carved them (most likely just before burial), the meaning and purpose of this act further reveals something about the conceptual and even poetical importance of these sculpted bannerstone forms. Rather than “ritually killing,” bannerstone makers as well as other artists of Ancient America appear to be repurposing artworks, using them in one way at first, then reconceptualizing them to accompany their dead underground, as a kind of memory-work for the living not entirely unlike the carefully constructed exhibition spaces or storage units of our museums. For the Indigenous people of the Americas the earth itself was often seen as a repository for cultural and personal objects, an underground space that was curated with things that continued to have meaning for the lives of communities for decades and even centuries.