Related works of art

In the Ancient Mediterranean

Masks

Active in c. 5000 B.C.E.–350 C.E. around the World

In North Africa

The Murúa Manuscripts: the earliest illustrated manuscripts of the Viceroyalty of Peru

c. 1580–90

Peru

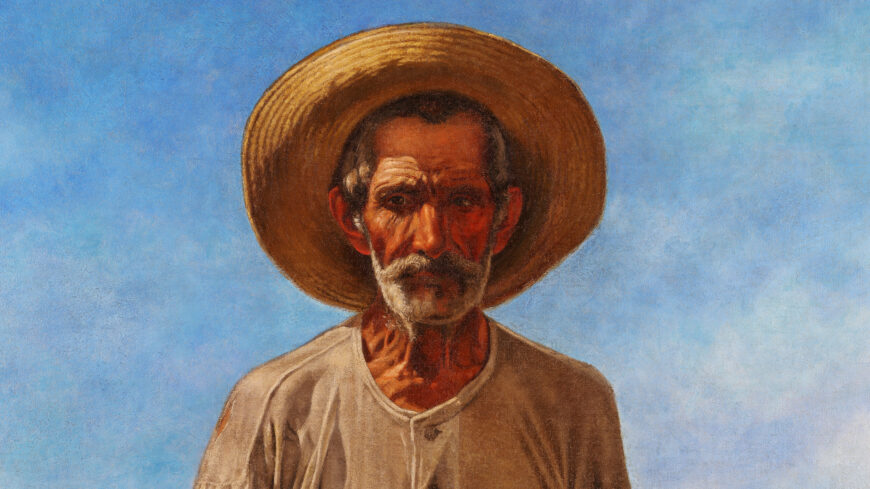

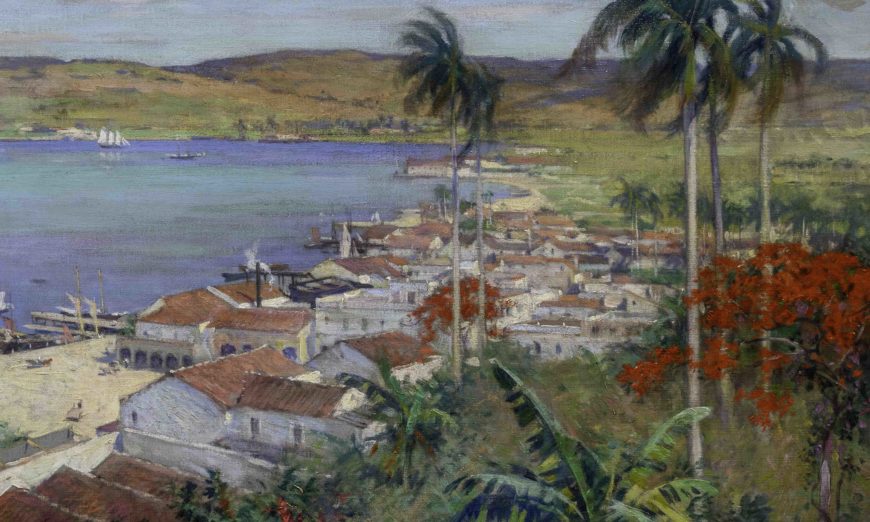

Francisco Oller, Still Life with Plantains and Bananas and Still Life with Coconuts

c. 1890

Puerto Rico

Gerardus Duyckinck I (attributed), Six portraits of the Levy-Franks family, c. 1735

c. 1735

United States

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!