Sand and sea

Peruvian cotton (_Gossypium barbadense_), (photo: Joe Lazarus CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Imagine living in the driest desert on earth located next to the richest ocean on earth. How would these extremes shape social and religious life? What kind of mythology would the drama of this landscape generate? Some ideas can be found in an ancient south-coastal Peruvian people now known as Paracas, from the later Inka Quechua word para-kos, meaning “sand falling like rain.” Paracas refers to both an arid south coastal peninsula and the culture that thrived in the region c. 700 B.C.E. to 200 C.E. The area is a starkly beautiful desert of ochre red, yellow, and gold sediments juxtaposed with the vivid Pacific Ocean. The ocean, enriched by the icy Peruvian current, is a haven for marine life. Ancient inhabitants, likely drawn to the ocean’s resources, had to make do with small coastal rivers trickling down from the Andes for fresh water and agricultural opportunities. In this environment, with visual contrasts so extreme the landscape approaches Color Field abstraction, small villages that depended on fishing and farming created one of the most extraordinary cultures and art traditions in the ancient Americas.

The Pacific bounty and the cotton grown in coastal river valleys gave Paracans the means to support a rich culture and forge reciprocal trade relationships with other Early Horizon highland cultures, principally Chavín. As a result, they assimilated and transformed art and ideas from the highlands, while inventing new beliefs and accompanying art forms that were largely inspired by their unique coastal ecology. Unlike other coastal and highland Andean communities, Paracans did not pursue monumental architecture, rather, they directed their considerable creative energies to textiles, ceramics, and personal regalia.

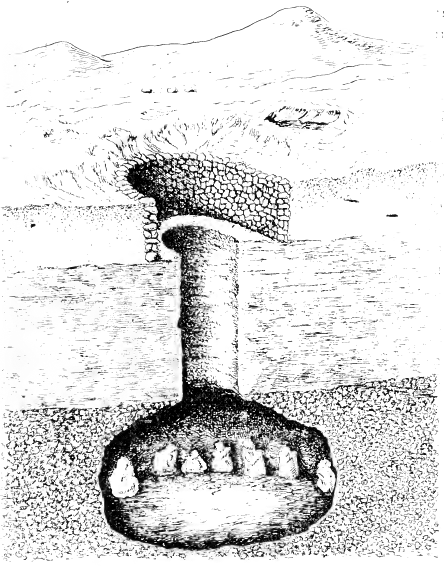

Illustration of mummy bundles at the bottom of a shaft-type tomb, from Julio C. Tello, Antiguo Perú: primera época, 1929, fig. 78

Belief in an afterlife led to the creation of subterranean burial chambers filled with elaborate mummy bundles and artifacts. Remarkably preserved in the arid coastal desert, the burials were forgotten and undisturbed for nearly 2,000 years. They were discovered in the early 20th century by Peruvian archeologist Julio C. Tello. The contents of these burials constitute the only known records of Paracas culture.

Paracas, detail of Linear Style embroidered mantle, 100 B.C.E.–100 C.E., camelid fiber, 267 x 131.9 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Mummy bundles and personal adornment

Most individuals were modestly wrapped in rough, plain cotton fabric to form a mummy bundle. Some adult males, presumably elites, were wrapped in multiple layers of vividly colored, elaborately woven and embroidered textiles made with cotton from the coast and camelid wool imported from the highlands. Ceramics, gold items, spondylus shells, feather fans, and individual feathers also accompanied these individuals.

Before his death and burial, an elite Paracas man would have been a dazzling sight in the desert, showing off concentrated finery that exuded status, power, and authority. These individuals are generally understood to be the religious and political leaders of Paracas chiefdom society, whose leadership and ritual duties likely continued in the afterlife. Such elites needed all their ritual attire and accessories to perform their duties and roles effectively on both sides of life and death, much like the pharaohs of ancient Egypt. Mummies may also have helped to maintain the tenuous desert agricultural cycle (often disturbed by El Niño climate events). As metaphorical seeds germinating the land, some bundles contained cotton sacks of beans rather than human bodies.[1]

Double-spout strap-handle vessel depicting a falcon (Paracas), 500-400 B.C.E., ceramic and resin-suspended paint, 11.43 × 12.38 × 12.38 cm (Dallas Museum of Art)

Burial artifacts

The Paracas achievements in ceramic and textile arts are among the most outstanding in the ancient Americas. The majority of Paracas ceramics were decorated after firing, with plant and mineral resin dyes applied between incised surface lines to build an image in abstract bands. In a final, transitional stage, pre-fire monochrome clay slips were applied to vessels in the shape of gourds, resulting in smooth, elegant wares.

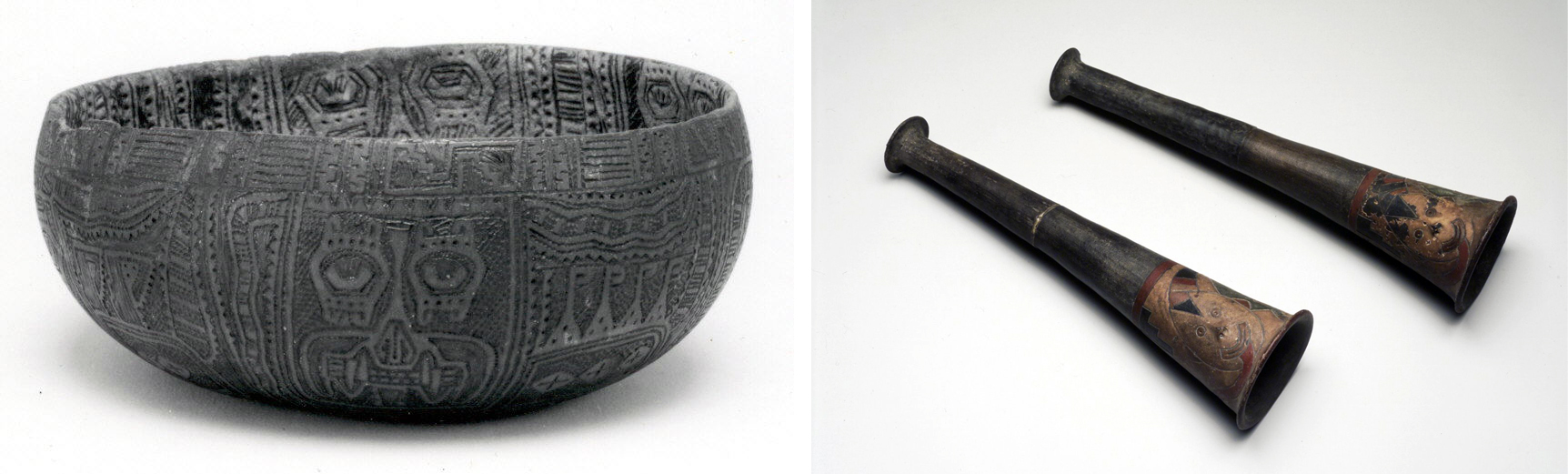

Left: Pyro-engraved gourd bowl, Paracas culture, 5th–4th century B.C.E., 6.4 x 15.2 x 14.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); right: Pair of ceramic trumpets with post-fire paint, Paracas culture, 100 B.C.E.–1 C.E., 29.1 x 7.9 x 7.9 cm and 30.2 x 8.3 x 8.3 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Other notable items found in the burials included pyro-engraved gourd bowls, as well as gourd rattles and ceramic bugles, revealing the culture’s interest in musical performance. Textiles were, without question, the most outstanding of the burial finds in both quantity and quality, with every known weaving and embroidery technique mastered. Their embroidered imagery is also a form of text and the source of nearly all interpretations of Paracas beliefs and conceptions of their ritual life.

Mythical imagery in textile art

Linear Style

Complex textile imagery was likely accompanied by equally complex oral narratives. At the start of the Paracas textile tradition, c. 700 B.C.E., the imagery is dominated by the traditional Andean animal triad of serpent, bird, and feline, rendered in an abstract style known as the Linear Style and accompanied by their own creation, the Oculate Beings.

Paracas, detail of Linear Style embroidered mantle with serpentine Oculate Being, 1–500 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 11.5 x 19.5 cm excluding fringe (The British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Oculate Beings were named for their enormous eyes, possibly inspired by the coastal burrowing owl or the enlarged eyes of a person in trance, and are believed to be key Paracan supernatural figures due to their frequent and enduring presence in Paracas art. Oculate Beings appeared in both humanoid and zoomorphic forms. Art historian Anne Paul identified eight distinct Oculate Beings based on different animals and poses: serpent, bird, and feline, symmetrical, seated, inverted head, flying, and with streaming hair.[2] Paracas embroiderers developed the visual potential of the Linear style to the highest degree, embedding images of animals and Oculate Beings into complex visual effects.

Block Color Style

Paracas, detail of Block Color style embroidered mantle with falcons, c. 100 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 298.9 x 137 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Beginning around 200 B.C.E., textile embroiderers added the curvilinear Block Color style to their production, resulting in an explosion of new forms and figures. Block Color embroidery broke away from the Linear Style iconographic template to include human figures in ritual costume, human/animal composite figures, and elaborate composites of multiple animals. Sprouting seeds, insects, flowers, serpents, sharks, the pampas cat, and in particular a wide variety of coastal and highland birds dominate this later phase of Paracas embroidery, and there are as many distinct figures as there are individual garments. This final, figural phase also often featured human figures in a state of flight or trance, akin to those found on both earlier and contemporaneous ceramics. While precise meanings remain elusive, the imagery suggests an intense interest in agricultural fertility, as well as an increasingly complex mythology and accompanying ritual activities.

An enduring enigma

Much about Paracas culture will always remain a mystery. Their artistic record reveals a set of beliefs and rituals reflecting their culture’s dependence on the natural world and concern with perpetuating agricultural cycles, the important role of animals in political and religious activities, and a deep investment in the afterlife. The major works of Paracas artists, particularly those expressed in the embroidered figures that embellish woven textiles, are a pinnacle of Andean textile art and acknowledged as among the most accomplished fiber arts ever created. In the trajectory of Andean art, Paracas stands as an independent, inventive coastal counterpart to Chavín. Paracas culture was also a vehicle for transferring both textile and ceramic technology and iconography to the slightly later, south coastal Nasca culture, before disappearing forever into the golden desert sand.