In America people are born in diverse colors, customs, temperaments and languages. From the Spaniard and the Indian is born the mestizo, usually humble, quiet and simple. [1]

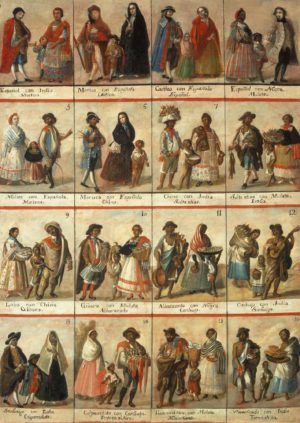

So states an inscription on José Joaquín Magón’s painting, The Mestizo, made in New Spain (Spanish colonial Mexico) during the second half of the eighteenth century. The painting displays a Spanish father and Indigenous mother with their son, and it belongs to a larger series of works that seek to document the inter-ethnic mixing occurring in New Spain among Europeans, Indigenous peoples, Africans, and the existing mixed-race population. This genre of painting, known as pinturas de castas, or casta paintings, attempts to capture reality, yet they are largely fictions.

José Joaquín Magón, El Mestizo/The Mestizo, second half of the eighteenth century, oil on canvas. 102 x 126 cm (private collection)

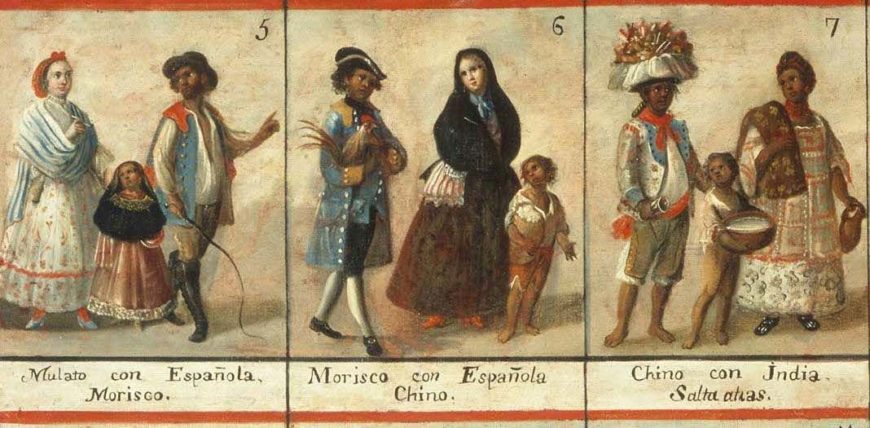

Typically, casta paintings display a mother, father, and a child (sometimes two). This family model is possibly modeled on depictions of the Holy Family showing the Virgin Mary, saint Joseph, and Christ as a child. Casta paintings are often labeled with a number and a textual inscription that documents the mixing that has occurred. The numbers and textual inscriptions on casta paintings create a racial taxonomy, akin to a scientific taxonomy. In this way, casta paintings speak to Enlightenment concerns, specifically the notion that people can be rationally categorized based on their ethnic makeup and appearance.

Detail of paintings 2–5, Francisco Clapera, set of sixteen casta paintings, c. 1775, 51.1 x 39.6 cm (Denver Art Museum, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Organization and labels in casta paintings

They are commonly produced in sets of sixteen, but occasionally we see sixteen vignettes on a single canvas. Costume, accoutrements, activities, setting, and flora and fauna all aid in racially labeling the individuals within these works.

The first position of the casta series is always a Spanish man and an elite Indigenous woman, accompanied by their offspring: a mestizo, which denotes a person born of these two parents. As the casta series progresses and the mixing increases, some of the names used in casta paintings to label people demonstrate social anxiety over inter-ethnic mixing and can often be pejorative.

For instance, a Spaniard and a mestizo produce a castizo (“burned tree”), while a Spaniard and a morisco (a muslim who had been forced to convert to Christianity) produce an albino torna atrás (“Return-Backwards”) and a No te entiendo (“I-Don’t-Understand-You”) with a Cambuja (offspring of an Indian woman and African man) makes a tente en el aire (“Hold-Yourself-in-Mid-Air”). Indigenous peoples who chose to live outside “civilized” social norms and were not Christian were labeled mecos, or barbarians.

Casta paintings convey the perception that the more European you are, the closer to the top of the social and racial hierarchy you belong. Pure-blooded Spaniards always occupy the preeminent position in casta paintings and are often the best dressed and most “civilized.” Clearly, casta paintings convey the notion that one’s social status is tied to one’s perceived racial makeup.

Spaniard and Indian Produce a Mestizo, attributed to Juan Rodríguez Juárez, c. 1715, oil on canvas (Breamore House, Hampshire, UK)

Detail, Spaniard and Indian Produce a Mestizo, attributed to Juan Rodríguez Juárez, c. 1715, oil on canvas (Breamore House, Hampshire, UK)

Spaniard and Indian Produce a Mestizo, attributed to Juan Rodríguez Juárez

Many famous artists, including Juan Rodríguez Juárez, Miguel Cabrera, and Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, produced casta paintings. Rodríguez Juárez created some of the earliest casta paintings, and Spaniard and Indian Produce a Mestizo (above), which displays the same subject as Joaquín Magón’s painting, is attributed to him. [2]

The painting displays a simple composition, with a mother and father flanking two children, one of whom is a servant carrying the couple’s baby. The Indigenous mother, dressed in a beautiful huipil (traditional woman’s garment worn by Indigenous women from central Mexico to parts of Central America) with lace sleeves and wearing sumptuous jewelry, turns to look at her husband as she gestures towards her child. Her husband, who wears French-style European clothing including a powdered wig, gazes down at the children with his hand either resting on his wife’s arm or his child’s back. The young servant looks upwards to the father. The family appears calm and harmonious, even loving. This is not always the case, however. Often as the series progresses, discord can erupt among families or they are displayed in tattered, torn, and unglamorous surroundings. People also appear darker as they become more mixed. Casta paintings from the second half of the eighteenth century in particular focus more on families living in less ideal conditions as they become more racially mixed. Earlier series, like Rodríguez Juárez’s, often display all families wearing more fanciful attire.

Patrons

But who commissioned these works and why? The existing evidence suggests that some of these casta series were commissioned by Viceroys, or the stand-in for the Spanish King in the Americas, who brought some casta series to Spain upon their return. Other series were commissioned for important administrators. However, little is known about the patrons of casta paintings in general. Yet, we can infer to a degree who might have commissioned such paintings. Because casta paintings reflect increasing social anxieties about inter-ethnic mixing, it is possible that elites who claimed to be of pure blood, and who likely found the dilution of pure-bloodedness alarming, were among those individuals who commissioned casta paintings.