African slavery as it exists amongst us . . . [is] the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution. . . . Our new government[’s] . . . corner-stone rests upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.Alexander Stephens, Vice President of the Confederate States of America, March 21, 1861 [1]

Historians today widely agree that slavery was the single most important cause of the Civil War. There is an abundance of textual evidence to support this, perhaps most famously an address given by Alexander Stephens known as the “Cornerstone Speech.” Stephens, the Vice President of the newly formed Confederate States of America (also known as the Confederacy) delivered the address to a crowd in Savannah, Georgia, at a critical moment: March 1861, just weeks after the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States. Georgia was one of seven southern states that had recently seceded (separated) from the United States with the intent of forming a new nation. Called to remark on the Confederacy’s new constitution, Stephens bluntly outlined the reasons that southern states had seceded and what they hoped to achieve as an independent nation: the preservation of slavery and perpetuation of white supremacy.

A “positive good”

Stephens was far from the only person to voice this reasoning. “Secession commissioners” who urged southern states to secede by speaking at legislatures and state conventions repeatedly cited their desire to protect slavery. [2] In fact, white southerners were not ashamed that millions of Black people were enslaved in their states; they proudly proclaimed that slavery was a “positive good.” [3] Although Abraham Lincoln—an antislavery Republican—had disavowed any intent to interfere with slavery where it already existed, slaveholders seized the opportunity of his election to break with the U.S. government and create a new nation where slavery could be protected forever. [4]

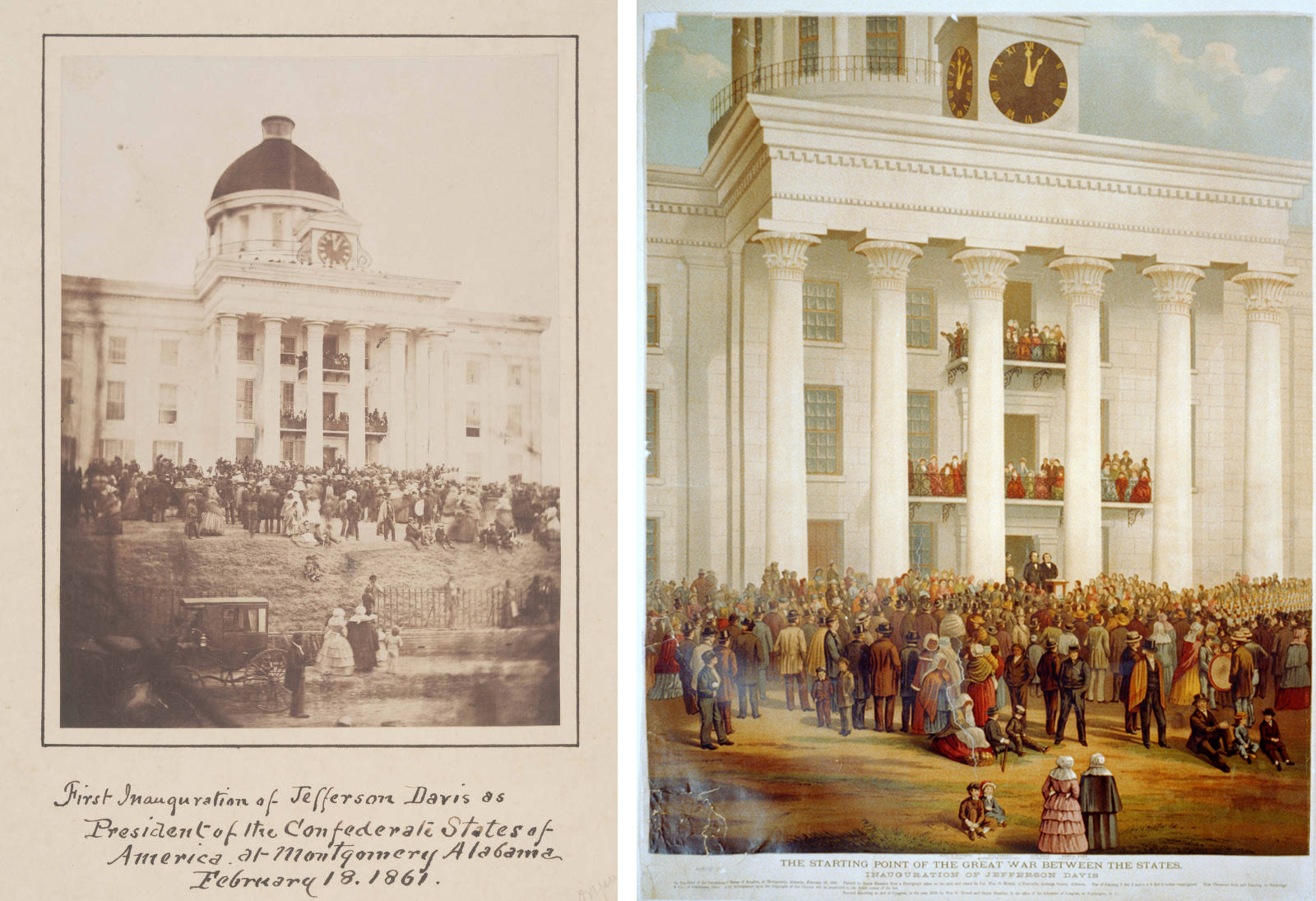

Thanks to the new technologies of lithography and photography (lithography was invented in 1796, and the first photograph was taken in 1826), we have images of the inauguration of Jefferson Davis and Alexander Stephens (both slaveholders), as president and vice president respectively, of the rebel break-away states. These images remind us of the importance of new technologies in disseminating images in the second half of the 19th century, but they also remind us that all images (even photographs) adopt a point of view and therefore must be approached critically.

Left: A. C. McIntyre, First inauguration of Jefferson Davis as President of the Confederate States of America at Montgomery, Alabama, February 18, 1861, photographic print, 19.9 x 14.7 cm (Boston Athenaeum); right: The starting point of the great war between the states: the inauguration of Jefferson Davis, 1878, chromolithograph, 76.6 x 60.8 cm (Library of Congress)

If we consider these two images of the inauguration—one a photograph and the other a color lithograph—we see people of all ages including some Black figures gathered around the Capitol building in Montgomery, Alabama. Davis and Stephens stand in the center of the podium facing the crowd. The chromolithograph on the right, made more than a decade after the end of the war, was based on the earlier photograph (left), but collapses the middle ground and narrows the composition to consolidate the crowd and focus on the grand portico, its balconies and the clock tower. We also see more clearly the faces of the figures and their interactions than we do in the early photograph. For these reasons, the lithograph condenses and heightens the importance of this moment. Which image is true? The answer is both and neither.

Alabama State Capitol Building photographed December 2021; statue at left noted in red: Frederick Cleveland Hibbard, Jefferson Davis, dedicated 1940; inset photo of star embedded in paving at the top of the steps where Davis stood during his inauguration as the President of the Confederacy (photos: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The power of these images and the moment they depict has echoed to the present day. A star embedded in the paving at the top of the steps of the Alabama State Capitol marks the location where Jefferson Davis stood during his inauguration as the President of the Confederacy, and a statue of him still stands nearby.

The war begins at Fort Sumter

A month or so after the inauguration, and just three weeks after Stephens delivered his Cornerstone Speech, the U.S. Civil War began at Fort Sumter in South Carolina (the first state to secede from the Union).

The Evacuation of Fort Sumter, April 1861, albumen silver print from glass negative, 12.6 x 9.4 x 2.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Gutzon Borglum, Alexander Hamilton Stephens, given 1927, National Statuary Hall, U.S. Capitol (photo: Architect of the Capitol, U.S. government work)

When it became clear that the United States intended to hold the fort despite the secession of South Carolina, Confederate forces attacked it. This was the first military action of the Civil War. Confederate forces reduced the fort to a ruin, and U.S. soldiers evacuated. The photographs of the aftermath of the battle at Fort Sumter stressed the destruction of the site and helped to strengthen the resolve of the Confederacy. This image, and others like it became powerful symbols—here was photographic evidence of the Confederacy’s strength.

By end of the war, the United States had defeated the Confederacy, more than 750,000 Americans had died, and slavery had been banned everywhere in the United States through a Constitutional amendment. [5]

Denial and the Lost Cause

After the war, white southerners fashioned a narrative (often referred to as the Lost Cause) that denied that slavery had any role in bringing about the Civil War, despite the evidence to the contrary. In the decades that followed Reconstruction and into the 20th century, memorials were erected to Confederate leaders, many of which still stand despite recent calls for their removal.

Memorials to Stephens, who had said the Confederacy’s “corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man” still stand in public and civic spaces, including one in the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., erected in 1927 during the Jim Crow era. The impressive space of National Statuary Hall in the Capitol, under a dome and surrounded by marble columns, was set aside in 1864 to serve as a hall to honor those who were “illustrious for their historic renown or for distinguished civic or military services such as each State may deem to be worthy of this national commemoration.” [6]

The artist who created the sculpture of Stephens, Gutzon Borglum, also worked on the enormous memorial celebrating the Confederacy carved on the side of Stone Mountain and the carving at Mount Rushmore. But the sculpture of Stephens may not remain in the U.S. Capitol for much longer. In an open letter to the Governor of Georgia in 2017, Stephens’s descendants wrote: “Confederate monuments need to come down. Put them in museums where people will learn about the context of their creation, but remove them from public spaces so that the descendants of enslaved people no longer walk beneath them at work and on campus.” [7] In June 2021, the House of Representatives voted to remove statues that honor Confederate leaders.

The causes of the Civil War in art

What do works of art reveal about the deep divisions that led to the Civil War? The collections of museums and archives, as well as public monuments, show us how artists captured the many issues that divided the nation in the years leading up to the Civil War, from the abolitionist movement to westward expansion, in photography, painting, sculpture, and popular prints. Visual arguments for and against slavery proliferated in 19th-century America, as defenders and opponents of human bondage sought to sway the opinions of the broader public. The new medium of photography, capable of capturing the visible world as never before, proved a valuable tool in this.

Frederic Edwin Church, The Meteor of 1860, 1860, oil on canvas, 10 x 17.5 inches (private collection)

Paintings, too, often addressed the issues of both prewar and wartime emotion using landscape as a metaphor—as the art historian Eleanor Harvey put it, “American audiences seemed eager to ascribe patriotic sentiments to the landscape as a means of channeling wartime emotions.” [8] For example, Frederic Church’s 1860 painting, The Meteor of 1860, depicts a meteor streaking through the night sky and its reflection in water below. Critics at the time saw the double fireball of the meteor as akin to shots being fired from artillery, and saw it and other atmospheric phenomena that appeared in the sky that year, through the lens of a war that was seeming more and more unavoidable.

When we examine the visual record of the Civil War, it is best to immediately ask who an image was made for, who made it, what it aimed to achieve, how it was understood at the time it was made, and how its meaning has changed. We must also consider what the visual record does not contain. For example, enslaved people rarely had an opportunity to create images; what they did create (such as textiles, baskets, carvings, dolls, and pottery) was less likely to be preserved than the works of free artists.

Elizabeth Keckley, Mary Lincoln dress, 1861, velvet, satin, and mother-of-pearl, 152.4 cm x 121.92 cm (National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

Extraordinary exceptions however do exist. Elizabeth Keckley overcame her brutal enslavement in Virginia, North Carolina, and Missouri, and became the dressmaker to First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln. She was able to purchase her own freedom and that of her son in 1852 using $1,200 she earned from her sewing and that she was able to borrow from her wealthy clientele. [9] Her 1861 purple velvet dress with satin piping and mother-of-pearl buttons was made for Mrs. Lincoln to convey that she was both “dignified and competent,” characteristics that had important political and diplomatic functions in the early months of the Civil War (the gown was worn in late 1861–early 1862).

The essays in this section

The essays in this section follow the thread of slavery in art as it was sewn through ideas about freedom, westward expansion, and the political landscape, from the founding of the nation to the start of the Civil War.

The first essay, “The problem of picturing slavery,” focuses on the experience of enslaved men and women living in a slave society in the first half of the 19th century. What visual and material evidence did they leave behind that helps us to learn about their lives? What can’t we learn from the visual record?

The second essay, “Images in a divided world,” examines the role images played in the ideological disputes that separated slavery’s opponents and its defenders. Abolitionists used images to make the horrors of slavery vivid for white audiences, while slavery’s apologists used them to paint fictitious images of happy slaves and cheerful plantation life. Both sides used the fledgling “science” of photography to advance arguments for and against Black humanity and citizenship.

The third essay, “Imagining the West, territorial expansion, and the politics of slavery,” discusses the visions of the West in art, and the effect these visions had on U.S. politics, as white Americans projected their aspirations and fears onto the future of the nation, heedless of its Indigenous and Hispanic residents.

Although the path from the founding of the United States in 1776 to its war of disunion 85 years later was tortuous, slavery—its past, present, and particularly its future—was at the heart of the conflict at every turn.