Atrial Cross, convento San Agustín de Acolman, mid-16th century. Speakers: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Beth Harris

Conventos

When we think of the conquest of the “New World,” we may immediately picture the violence of the military encounter between Spaniards and the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. While the process of colonization began through bloodshed, relatively few Indigenous peoples fought against Spanish soldiers.

Convento San Agustín de Acolman, mid-16th century (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Instead, their first exposure to the new conquerors was often within the large walled complexes called conventos (missions). Built by Indigenous populations alongside mendicant friars, these compounds contained a church, cloister, patio (also known as an atrium), and an outdoor chapel. Within the conventos Indigenous people were baptized and taught the tenets of the Christian faith. The outdoor walled atrium hosted autos (religious plays) as well as religious processions that were staged in a counter-clockwise direction, imitating the direction of Nahua rituals (the Nahua are an Indigenous people of Mexico and El Salvador).

Crenellated (notched) roofline, convento San Agustín de Acolman, mid-16th century (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

One of the most celebrated Mexican conventos is the Augustinian mission of San Agustín de Acolman (Acolman was a Nahua village located just north of Mexico City). Built in the mid-sixteenth century, the complex features a rusticated façade with boldly projecting stones, and a crenellated (notched) roofline, giving it a fortress-like appearance. This architectural style was common among the conventos of New Spain (the former Spanish colony that is now Mexico, Central America, and the southwestern United States). San Agustín de Acolman’s architectural style suggests a protective function, and may have referenced the temple of Jerusalem, celebrating Mexico as a “New Jerusalem” where the Christian faith could flourish.

Atrial Cross, convento San Agustín de Acolman, mid-16th century (now located across the street from the convento) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Atrial Cross at Acolman

Carved INRI at top and pierced heart below (detail), Atrial Cross, San Agustín de Acolman (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The famed atrial cross of Acolman originally stood at the center of the large atrium, hence the term “atrial” cross coming from its location. It was carved by an Indigenous artist under the instruction of an Augustinian friar. The cross, similar to others created in the early years after the conquest, is carved with complex iconography. The vertical shaft features the INRI plaque at top, below which is carved the Augustinian emblem of a heart pierced with arrows. [1]

Column (detail), Atrial Cross (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The remainder of the shaft features the Arma Christi (literally, “weapons of Christ,” the objects associated with the Passion) including a chalice, cock, pliers, spear, ladder, nail, and a human skull. These objects relate to the story of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem and his suffering at the hands of the Roman soldiers before his death on the cross and eventual resurrection.

The objects are isolated from one another, displaying an affinity with the Aztec pictographic writing system. Each “instrument,” like an Aztec glyph, is boldly outlined and reduced to simplicity of forms for the sake of legibility. Within the ritual theater of the convento, the cross served as a teaching tool for new Nahua converts to learn an episode of the Passion story by metaphorically zooming in on the relevant “glyph.” For example, the spear would illustrate the story of the Roman soldier who pierced Christ’s side, and the ladder would narrate the deposition, or removal of Christ’s body from the cross.

Christ’s face (detail), Atrial Cross, San Agustín de Acolman, mid-16th century (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

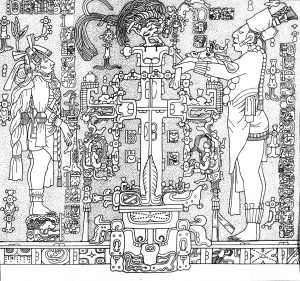

Panel from Temple Of The Cross, Palenque (Maya), Late Classic Period (Schele, #174)

In addition to these symbols, the cross’s arms feature vegetal designs, a trope connected to the Indigenous “World Tree,” the symbolic center of the universe from which the human race emerged. Spaniards of the period noted that Indian images of the World Tree bore similarities to the Christian cross, surmising that Saint Thomas the Apostle had introduced the cross to the Americas in Biblical times, but that his efforts were destroyed by the workings of the Devil. In fact, the World Tree was an ancient symbol in Mesoamerica (modern-day Mexico and much of Central America), and had no original connection to Christ’s martyrdom. Rather than Christ’s body hanging on a cross as is typical for a crucifix, the center of the Acolman cross features his boldly projecting face, perhaps also connecting it to the World Tree as a place of creation.

Virgin Mary and skull (detail), Atrial Cross, San Agustín de Acolman (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Alternatively, Christ’s face may be a rendering of the sudarium, or the veil that Saint Veronica used to wipe Christ’s blood and sweat as he carried the cross to his execution. The veil that became imprinted with his visage is one of the arma Christi which might explain its inclusion on the atrial cross.

Finally, the base of the cross includes a rendering of the Virgin Mary alongside a human skull, a reference to Calvary, or “the place of the skull,” the burial place of Adam and the hill upon which Christ died. This complex iconography derived from European print sources and was executed by Native artists in Native styles. This legacy is clearly visible when comparing the cross to pre-Hispanic Nahua monumental stone sculpture in the round that similarly features bold designs executed in varying relief.

A hybrid style

“Tequitqui” is one term given to this type of early colonial sculpture from Central Mexico that displays Indigenous symbolism and style. Created as a collaborative effort, the hybrid atrial cross offers a fascinating look into the interactions between Spanish friars and Nahua converts in the years directly following the conquest of Mexico. While Spaniards wielded power as conquerors, Indigenous people nevertheless played a major role in shaping the new colonial society. At Acolman, we can see these interactions at play, manifested in this masterfully carved monumental stone cross.

Notes:

[1] INRI are initials for the Latin words that Pontius Pilate had written over the head of Jesus Christ on the cross (Iēsus Nazarēnus, Rēx Iūdaeōrum, Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews).

Additional resources

Samuel Y. Edgerton, “Christian Cross as Indigenous ‘World Tree’ in Sixteenth-Century Mexico,” in Exploring New World Imagery, edited by Donna Pierce (Denver: Mayer Center for Pre-Columbian and Spanish Colonial Art, 2002), pp. 16–24.

Jaime Lara, City, Temple, Stage: Eschatological Architecture and Liturgical Theatrics in New Spain (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2004).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”acolman,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:04] We’re looking at the famous atrial cross at the site of a very early mission, a convento, a place where the Indigenous population was converted very soon after the Spanish conquest.

Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:17] This cross at Acolman would have originally been in the center of the atrium, but today it’s just across the street from the entrance to this missionary complex, this convento.

Dr. Harris: [0:27] An atrium was an important part of the convento.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:31] It was this very large open courtyard where you would have processions, where newly converted individuals would be taught about Christianity. They’d be preached to from this open elevated balcony chapel here at the convento, so it was a multi-purpose, very important space.

Dr. Harris: [0:47] Right in the middle of that space would be a cross.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:50] This particular cross is decorated in such a way that it’s very didactic, meaning that it’s this exceptionally important teaching tool to help the newly converted Indigenous population learn about Christianity, and particularly the Passion of Christ, or the events leading up to the Crucifixion.

Dr. Harris: [1:07] We read a series of symbols that tell us more about Christ’s suffering.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:12] While inside the convento, particularly in the cloisters, you have these wonderful murals that are displaying for us the various scenes of the Passion, here we have this condensed, symbolic version of that, where we see symbols associated with the Passion, things like the rooster that was supposed to crow three times as a sign that Saint Peter would denounce Christ.

Dr. Harris: [1:34] We see the crown of thorns that Christ wore when he was on the cross.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:37] And a variety of these other instruments.

Dr. Harris: [1:39] Right above Christ’s head, I see that symbol associated with the Augustinians of the pierced heart

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:45] Marking this atrial Cross as being part of this Augustinian convento.

Dr. Harris: [1:49] The arms of the cross end in flowers.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:53] The arms are actually covered in foliate imagery. There’s a particular type of marigold, which in Nahuatl, the language of the Nahua population, is called “cempaxochitl,” which is a particular type of marigold that you still see used for Day of the Dead, and it had this relationship to death.

Dr. Harris: [2:10] There might have been multiple ways of reading this image.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:14] If you’re an Indigenous viewer, using these flowers associated with death might have relevance in relation to the martyrdom of Christ. What’s also important to keep in mind is that there could have been this bilingual process, or what we could even call visual bilingualism.

[2:28] The symbol of the cross is not something introduced by the Europeans. It’s a longstanding ancient symbol here in Mesoamerica that had associations with fertility, with the cosmos, with the center of the universe.

Dr. Harris: [2:42] So an Indigenous viewer looking at this could have read these images or this cross simultaneously in two different ways, and the artist was likely an Indigenous artist.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:53] The labor used to build these conventos and to decorate them were drawn from the Indigenous population.

Dr. Harris: [2:59] Then, down at the bottom of the cross, we seem to see an image of Mary and other symbols related to the Passion of Christ.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:06] We think this is the Virgin Mary in part because her arms are crossed over her chest, which is, at this point in time in Europe, how Mary is usually shown when she’s grieving for her dead son.

[3:17] Some of the other symbols that we see include a skull, a twisted snake, and even what looks like a disc of some sort.

Dr. Harris: [3:25] The date of this cross is so early in the history of New Spain.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:31] This cross was probably constructed sometime between the 1540s and 1560s. It’s representative of atrial crosses that you would see at other conventos.

[3:39] Just to go back to what we said earlier about this being an educational tool in the center of the atrium, [it] speaks to the need for educating people about the tenets of Christianity, about what it means to be Christian in the wake of the conquest and the evangelization that’s following.

Dr. Harris: [3:57] And the important role of images in doing that.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:00] Images were crucial to the conversion process because they were a primary means of teaching people about Christianity in the face of language barriers.

[4:08] [music]