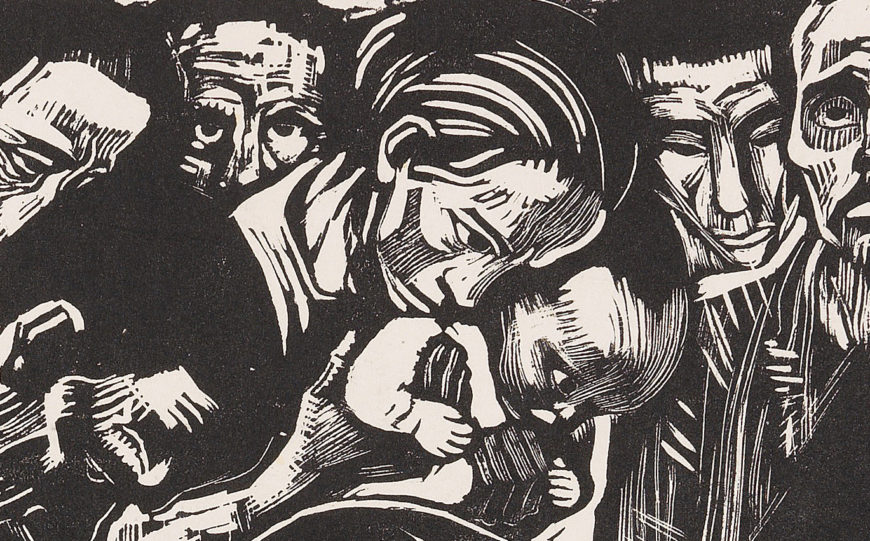

Käthe Kollwitz, Memorial Sheet of Karl Liebknecht (Gedenkblatt für Karl Liebknecht), 1919–20, woodcut heightened with white and black ink, 37.1x 51.9 cm (The Museum of Modern Art)

Printmaking

In the political turmoil after the First World War, many artists turned to making prints instead of paintings. The ability to produce multiple copies of the same image made printmaking an ideal medium for spreading political statements. German artist Käthe Kollwitz worked almost exclusively in this medium and became known for her prints that celebrated the plight of the working-class.

The artist rarely depicted real people, though she frequently used her talents in support of causes she believed in. This work, In Memoriam Karl Liebknecht was created in 1920 in response to the assassination of Communist leader Karl Liebknecht during an uprising of 1919. This work is unique among her prints, and though it memorializes the man, it does so without advocating for his ideology.

History and politics

From the end of the First World War in late 1918 to the founding of the Weimar Republic (the representative democracy that was the German government between the two World Wars) in August 1919, Germany went through a period of social and political upheaval. During this time, Germany was led by a coalition of left-wing forces with Marxist sympathies, the largest of which was the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Other, more radical groups were grappling for control of Germany at the same time, including the newly founded German Communist Party (KPD).

The Socialists and Communists both wanted to eliminate Capitalism and establish communal control over the means of production, but while the Socialists believed that the best way to achieve that goal was to work step by step from within the Capitalist structure, the Communists called for an immediate and total social revolution that would put governmental power in the hands of the workers. In this spirit, the KPD staged an uprising in Berlin in January 1919. Military units called in by the SPD suppressed the uprising and captured two of the leaders, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. Liebknecht and Luxemburg were murdered while in custody on January 15, 1919. Their deaths struck a chord across the left-wing landscape and they were widely celebrated as martyrs to the Communist cause.

Kollwitz was not a Communist, and even acknowledged that the SPD (generally more cautious and pacifist than the KPD), would have been better leaders. But she had heard Liebknecht speak and admired his charisma, so when the family asked her to create a work to memorialize him she agreed.

A Lamentation

Memorial Sheet of Karl Liebknecht is in the style of a lamentation, a traditional motif in Christian art depicting the followers of Christ mourning over his dead body, casting Liebknecht as the Christ figure. The iconography would have been easily recognizable by the masses who were the artist’s intended audience.

Max Beckmann, “The Martyrdom,” plate 4 from Hell, 1919, lithograph, 54.7 x 75.2 cm (The Museum of Modern Art)

Other memorial works

Several artists at the time created memorial works for Liebknecht and Luxemburg. The most well known (along with Kollwitz’s work) are Max Beckmann’s “The Martyrdom” from his portfolio Hell of 1919 (above), and Conrad Felixmüller’s People Above the World from that same year. In contrast to those works, Kollwitz’s In Memoriam Karl Liebknecht focuses not on the man himself, but on the workers who had put their faith in him,. The focus on those broadly affected, rather than those in the spotlight is a constant theme in the artist’s work, reflected in her most famous works from the War cycle, which depict not the soldiers or the fighting, but the suffering of the women and children left behind and starving.

The composition

The composition divides the sheet into three horizontal sections. The top section is densely packed with figures. Their faces are well modeled and have interesting depth in themselves, but the sense of space is very compressed – the heads push to the foreground and are packed into every available corner of space. It gives the impression of multitudes coming to pay their respects, without compromising the individuality of the subjects.

The middle strata contains comparatively fewer details, further emphasizing the crowding at the top of the printing plate. This section draws attention to the specific action of the bending mourner. His hand on Liebknecht’s chest connects this section to the the bottommost level of the composition, the body of the martyred revolutionary.

Mourning woman holding a child (detail), Käthe Kollwitz, Memorial Sheet of Karl Liebknecht (Gedenkblatt für Karl Liebknecht), 1919–20, woodcut heightened with white and black ink, 37.1x 51.9 cm (The Museum of Modern Art)

Above the bending mourner, a woman holds her baby up to see over the heads of those in front of them. Women and children were a central concern of Kollwitz’s work, making her a unique voice in a creative environment dominated by young men (in fact, Kollwitz was the first woman to be admitted into the Prussian Academy).

Woodblock prints

Woodblock printing is a technique in which a design is carved into a slab of wood which is then covered with ink and printed onto paper. Ink coats the original surface of the wood block, which prints as black, while the cut away areas stay the color of the paper. This is different from printmaking methods such as engraving in which the ink is caught in the recesses carved into the metal plate by the stylus and therefore the lines print black and the untouched areas of the plate come out white in the print.

The German Expressionist artists, in particular Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and the Brücke group, used woodcuts as early as 1904 to capture the rough, vital energy that they perceived in the work of so-called “primitive” societies without a fine art tradition.

Kollwitz’s career overlapped with the German Expressionists but she was not an Expressionist herself and was about a generation older than most of them. Her use of such a trendy technique was uncharacteristic, and in fact, she only worked in woodblocks for a few years after the First World War. Kollwitz created some of her most powerful and affecting work in this style, including the War print cycle of 1924. She embraced the raw effect of woodblock printing to create pieces works that have cast off the subtlety and finesse of her earlier work in etching and lithography. Kollwitz’ felt that her protest against the horrors of war was best communicated in the rough edges and stark black and white that woodblock prints afforded.